I look for things we pass by every day, overlooked wonders in our own backyards. For instance, here’s a picture I took of a bee on a dandelion. Could anything be more humble, more commonplace? Many people hate dandelions, treat them as weeds, and quite a few others aren’t crazy about bees either. People like food but hate insects. Most of our food comes from flowering plants pollinated by insects. Insects flick the switch that operates the food factory of our planet.

Pictures can do many things. If I called my photo Dandelion and Bee, it wouldn’t trigger much curiosity. Instead, I call it Messenger of Love after the Kahlil Gibran poem: “To the bee, a flower is a fountain of life. To the flower, a bee is a messenger of love.” (excerpt from On Pleasure, from The Prophet. Knopf, 1923) So it’s a picture of symbiosis, microcosm, ecosystem. Easy for anyone to understand. And yet, there’s a question in it. The first question is, is there anything unusual happening here? You have to look closely to see. There may be several good answers, but what I have in mind is the pollen storm that greets the arrival of this dedicated bee. What a dusting he endures in exchange for a free meal! A recent documentary, My Garden of a Thousand Bees, shows newly-hatched bees landing on flowers. At first, the inexperienced bees dive into the heart of the flower and get splattered from head to toe. With more practice, they become better pilots and neater collectors. In my photo of the bee, I’ve captured this special moment of youthful enthusiasm and ineptitude. Is it ineptitude or is it joy?

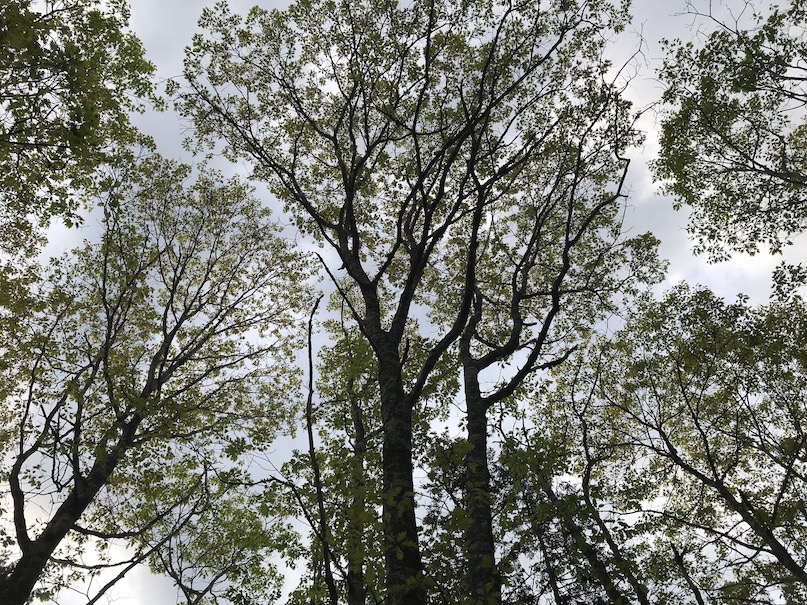

This spring, I entered the forest at our Centre by the Sea and looked up at the emerging canopy. It couldn’t have been more than a day or two after the first leaves appeared. I was struck by how the leaves fill in every inch of space, how the green umbrellas interlock. But these are no ordinary umbrellas! They eat the sun, alter the chemistry of air, rain upwards into the clouds. When I get back in my studio and review the shots I’ve just taken, this one gives me pause. I ask myself, where on the property did I take this photo? Without a horizon, there are no landmarks to ground myself. It is impossible to place, disorienting. We’re not used to looking up, not used to being dwarfed. How many human giants do you know? Not many. Every tree is a giant, linking earth and sky, possessing powers that elude us.

To see everyday scenes with fresh eyes, may require some disorientation, or a touch of imagination. Attention to detail. Seeing foreground and background at the same time.

I was surprised to discover this nest so close to the tracks. A sign perhaps that the railway has been abandoned. As industry sputters, birds recolonize their ancestral territory. Neither birds nor people are visible in this image, but we’re aware of both by these familiar signs. The image contrasts nature’s engineering with human engineering. The nest is fragile, built with storm-tossed twigs and grass; the track is made of more enduring materials, but is also prone to forces of change and abandonment.

I showed this image to a friend, a United Church minister, whose spiritual outlook on life surfaces in different contexts. His first impression was: we leave the nest and begin our journey, travelling far from our point of origin. Birth, life and death: the bittersweet cycle of transient beings.

So often I take pictures of nature and go out of my way to avoid signs of human presence, but I’m trying to retrain my eye to allow human disruptions to sit side by side with picturesque elements. When I do, the results are often surprising and reflect a core belief of mine that, whether we like it or not, we cannot understand nature except through the lens of culture. Conversely, I think of ecology as a human research project in which people attempt to escape the traps of human-centric thinking.

My wife Kathleen emptied a bucket at our wellness centre on a cold autumn day. To her surprise, the accidental contents of the bucket had frozen, maintaining the shape of the container. The evidence quickly disappeared after one afternoon sitting in the warm sun. In my photo, what evidence do you see? Evidence of oak trees. Evidence of precipitation. Evidence of human presence, human neglect, human delight, chance. Evidence of change of weather, freezing temperatures and thaw. Evidence of a bucket without the bucket.

I once entered this photo in a landscape photography contest. The image came in seventh place, sadly no medals or honorable mentions. I wondered at the time, as I’m sure the judges did as well, does this qualify as a landscape photo? I suspect arguments could be made for and against, which opens a second, more serious question:

What is a landscape? How might an artist, a philosopher, a carpenter or a biologist answer? An artist might declare that a landscape is nothing without water, without a play of light and clouds, seasonal rhythms. A philosopher might define related concepts, and start by saying that a view is all you can see from one spot; a landscape is many views put together in your mind by memory, habit, anticipation and repetition. A carpenter might point out that the sturdy deck gives a toehold on the landscape. If the carpenter brought his children along with him and these children liked to explore, run, climb and swim, he’d probably point out that these too are aspects of a landscape. A biologist might say, a landscape is an invisible food web. Or a landscape is home to a thousand leaves that disappear from one season to another as if by magic.

This is why I take pictures: to collect evidence of my journeys, to share with friends a few simple observations and questions. To find joy in change of seasons and to experience wonder, surprise and delight in the world around me. I hope others feel the same.