In line with Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, Yeats’s Sailing to Byzantium, Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, is Hermann Hesse’s gem-like novella, Journey to the East (1932). The story begins with a troubled narrator hinting at a glorious adventure that he is not at liberty to disclose fully. Nor could he if he tried because his memory has been impaired over time due to illness and suffering. The narrator, HH, also hints that this life-altering adventure has incurred ridicule by skeptics and by those who have not been exposed to the true story. Thus begins this allegory of a search for meaning and unattainable truth.

My first surprise as a reader was to discover that the journey is not made by an individual but by a group, the mysterious League with its many secrets and ceremonies. Within this group, individuals are encouraged to identify their own specific goals. The narrator comments: “Many members of the League set themselves goals which, although I respected, I could not fully understand. For example, one of them was a treasure-seeker and he thought of nothing else but of winning a great treasure which he called Tao. Still another had conceived the idea of capturing a certain snake to which he attributed magical powers and which he called Kundalini. My own journey and life goal, which had coloured my dreams since my late boyhood, was to see the beautiful Princess Fatima and, if possible, to win her love.”

These are the treasure of the East: Chinese philosophy, Indian medicine, and Arabian fable. The journey is fantastic, the language ecstatic and playful:

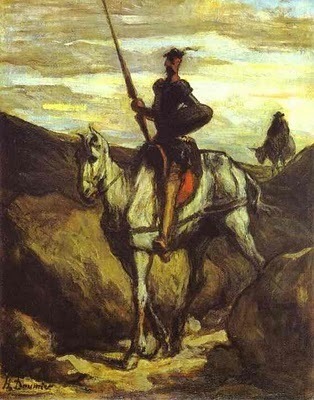

“One of the most beautiful experiences was the League’s celebrations in Bremgarten; the magic circle surrounded us closely there. Received by Max and Tilli, the lords of the castle, we heard Othmar play Mozart on the grand piano in the lofty hall. We found the grounds occupied by parrots and other talking birds … I shall always remember how Don Quixote stood alone under the chestnut tree by the fountain and held his first night watch while the last Roman candles of the firework display fell so softly over the castle’s turrets in the moonlight, and my colleague Pablo, adorned with roses, played the Persian reed-pipe to the girls.” (p 52)

Euphoria quickly turns to despair. “There was nothing else left for me to do but to satisfy my last desire: to let myself fall from the edge of the world into the void – to death.” The quest is not as easy or straightforward as it seemed. As HH loses his way, he starts to doubt himself and loses the ability to communicate with others. He seeks help, but ends up being accused (in a trial) of betraying the League and its values.

From initial champion of the League and its most grateful adherent, the hero fails the first test he encounters. However he is given a second chance. HH is ordered to search the archive for his own file. “A shudder went through me at the thought of what I should still learn in this hour. How awry, altered and distorted everything and everyone was in these mirrors, how mockingly and unattainably did the face of truth hide itself behind all these reports, counter-reports and legends! What was still truth? What was still credible? And what would remain when I also learned about myself, about my own character and history from the knowledge stored in these archives? (p. 106)

In a Goodreads review, Ben Winch describes Hesse’s subject: “The crux of it is, it’s the story of a failure. An inevitable failure, I would say, but as Hesse himself says early in the piece, “the seemingly impossible must continually be attempted”. What, then, is the seemingly impossible attempt made here? It’s twofold: the telling of an untellable story, the making of an impossible journey … but in showing an awakening from the inside out it achieves something difficult and valuable and profound. And besides, it’s beautiful. Unique. Magical.”

Susan Budd comments (also on Goodreads): “Rereading this book now, at the same age Hesse was when he published it, I must acknowledge my own desertion of the journey, my own forgetfulness and unfaithfulness to the league. I even sold my violin ~ figuratively speaking. And now I long to return.”

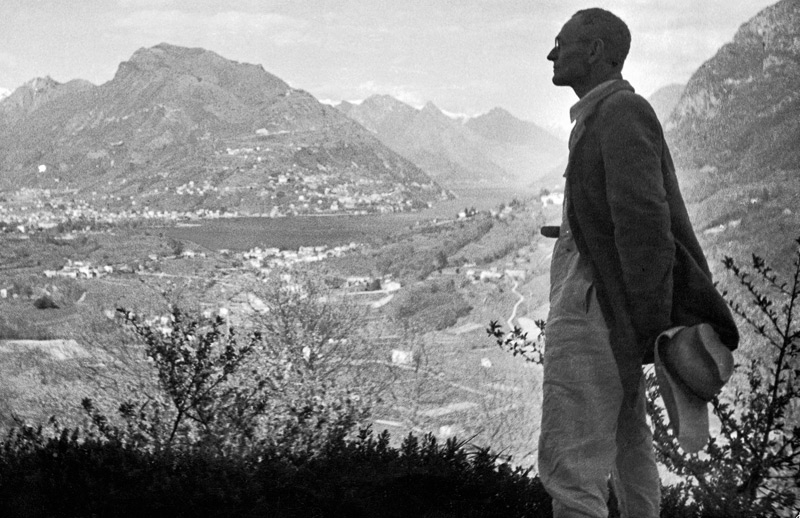

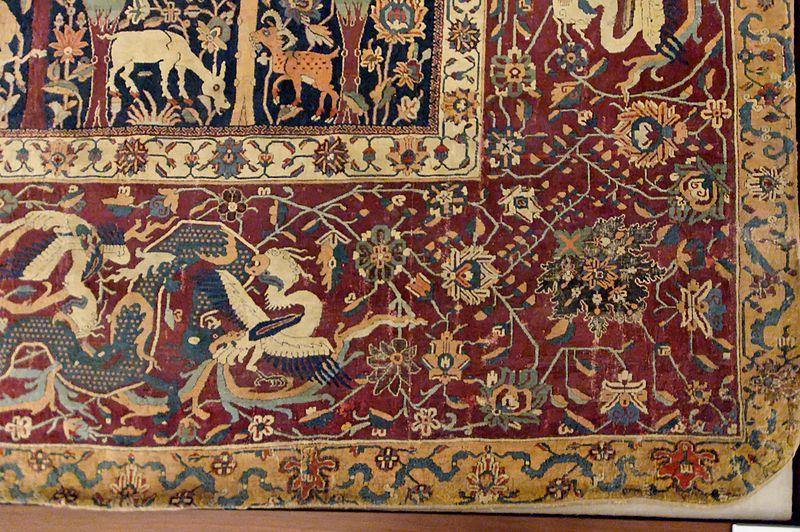

In my response to this story, I decided to choose three art objects: a painting of Don Quixote, the mad knight whose own quest is ridiculous and impossible, yet endearing. The historic Mantes carpet features a mesmerizing design where figures of animals and birds emerge and disappear among tangles of flowers and geometric vines. I also show a modern-day carpet in the process of construction. Unlike works of fiction or paintings where the artist roughs in a draft, then goes back and adds detail, the rug emerges fully formed from one end to the other. I end with a photo of my own, taken at the Gaudi Museum in Barcelona. The artist’s use of broken ceramic pieces to form a twisting rain gutter demonstrates his playful spirit, and a merging of everyday materials and beautiful design for a useful end product. The pigeon in the picture reinforces how effortlessly Gaudi’s work blends with nature.

All of these art elements figure in Hesse’s conception of the Journey: the madness inherent in chivalry, the mesmerizing loss of self, craftsmanship of a high order, playfulness, beauty, and utility.