People either love Matisse or hate him. His work strikes an immediate cord that bypasses thought. Most art histories relegate Henri Matisse (1869-1954) to a branch of early 20th century Expressionism that contributed to the vocabulary of radical modernism. As time passes, it becomes increasingly difficult to grasp the essence of this alarm-provoking originality. If anything, Matisse is damned now for being too tame, too concerned with serenity and beauty. In an effort to place a little more nuance in an understanding of his work, I touch here on a few ideas and strategies Matisse shares with Symbolist art.

Matisse’s teacher was Gustave Moreau (1826-1898). Moreau is famous for creating beautiful dream-like images, full of rich colour, elaborate patterns, ethereal beings and exotic settings. Moreau is invariably linked with the late-19th century movement known as Symbolist Art, which was a counter response to Naturalism and Impressionism. Impressionism, when not found on shopping bags and pretty calendars, has something to do with the scientific observation of light effects, with a sense of the transience of modernity, with an emphasis on contemporary subject matter, especially outdoor scenes painted on the spot. In contast to this, the Symbolists turn to literature and mythology for inspiration. Symbolist artists, inspired by writers such as Baudelaire and Rimbaud, pursued their desires into the realm of decadence, driving their imaginations to intoxicating heights. They reintroduced themes of psychological conflict, sublime isolation, exotic characters and locations. Symbolist art is imaginative but escapist, promoting art for art’s sake and ignoring current social problems. It stresses originality and genius to the point of being obscure, occult or hermetic. Part of this mystical impulse is the desire to unite contrary things, to come up with a cosmic all-encompassing vision of the world rather than depict a specific scene or localized street corner. Art historian Edward Lucie-Smith notes that “suggestiveness and ambiguity were the very essence of Symbolist poetry and art.” (Symbolist Art, 1972, p. 15) Allegories are one means of achieving this cosmic yet suggestive aim.

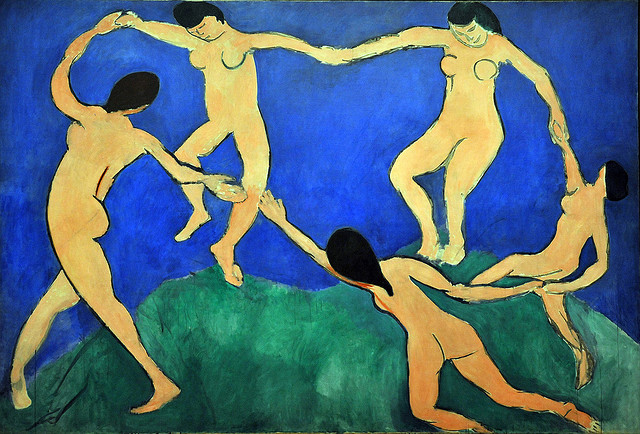

Matisse’s themes–the joy of life, the dance, music, the dreamer, the circus, the artist’s studio–touch on Symbolist ideals. In Dance, 1909, Matisse presents a timeless allegory that recalls a distant golden age. It is a portrait of community in motion; the harmonious circle of nude dancers allows for a rhythm of contrasts: up and down, large and small, fast and slow, enclosed and open. The work is dynamic and interconnected, as if a chain of vitality flows from one figure to another. If one dancer loses balance and falls, then all will feel the effects.

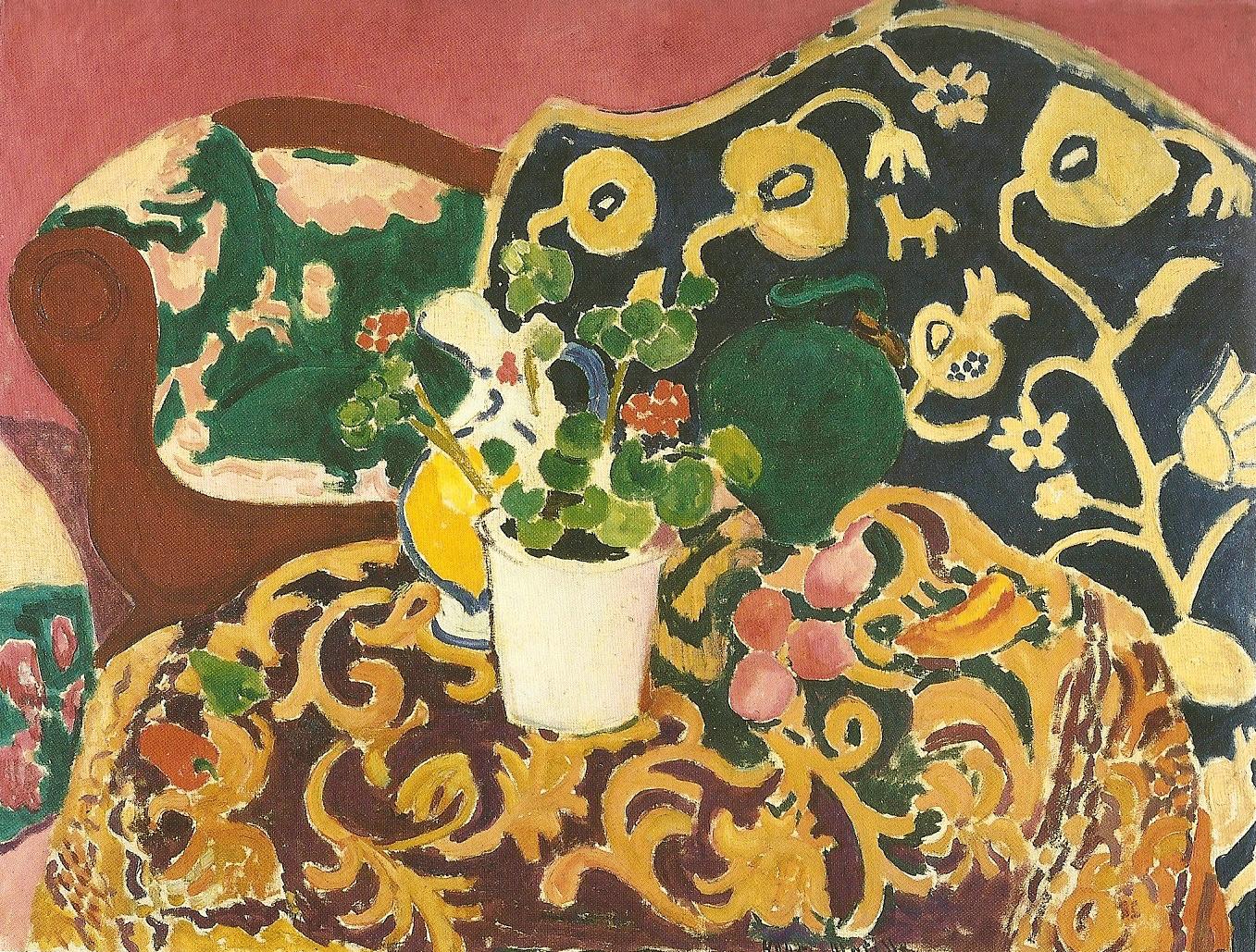

Matisse’s affinity for Symbolist art extends to his still life paintings. In the history of art, the still life is often heavily symbolic, with the addition of skulls, coins and clocks making comments on the fleetingness of life and the things we value. Matisse takes a slightly different approach, turning his still life images into cosmic fields that alternate between microcosm and macrocosm. His over-riding strategy is to bring inanimate objects –floral patterns, statues, mirrors, rugs, paintings within paintings—to life, blurring the distinction between nature and artifice. His inventive and witty analogies link one thing to another–a pot of flowers fuses with the floral motif on a background drapery, while household fruits lay scattered across the branches of a printed tablecloth. These paintings excite the senses, but also confuse and confound the viewer as foreground and background, interior and exterior space blend together. The wildly exuberant patterns are sensuous and suggest a joy of life as well as a richness of life. Vine-like surfaces, full of nervous energy, are hard to contain within the confined apartments and studios that are the most frequent settings. These works awaken strong affective responses, inspiring indescribable feelings.

There is another way that the artist uses symbols. It is not the elaboration of information, a richness of detail or truth-to-life that makes something a symbol. Rather the reduction of information into a highly distinctive form that jogs the memory and triggers recognition is a key element of any symbol. By simplifying forms and colours, Matisse turns the goldfish bowl shown above into a miniature world. His tiny sculpture of a reclining nude changes scale and appears monumental. In the process, the figure comes to life as a bather. The studio interior is all at once a forest glade, the vase of flowers serving as a canopy arching overhead. The rich field of colour creates an indeterminate free space, allowing the imagination to make these transformations possible.

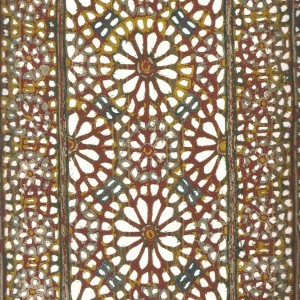

Sample from Matisse's private fabric collection: North African appliquéd hanging, late 19th century.

Growing up in a cloth-making region of north-eastern France, Bohain-en-Vermandois, Matisse came across a wide assortment of pattern books and textile samples, samples he collected throughout his life and incorporated into his art. (This connection to fabric design formed the basis of the exhibition “Fabric of Dreams” held at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 2005.) Matisse’s paintings feature patterns drawn from diverse cultures and regions. These patterns when draped across the surfaces of a room turn a domestic space into a stage set, inspiring a sense of play and fantasy, as well as creating visual rhythms and associations of exotic unknown elements. Fantasy and the exotic are key themes of Symbolist art, as is the escape or transcendence of everyday realities. Many modern artists come across as alienated and brooding prophets of the sick soul. In contrast, Matisse comes across as a kind of therapeutic hedonist, a doctor of pleasure, offering us sanctuaries where boundaries dissolve and the energy of the imagination is released.

Conclusion: Matisse’s work is daringly modernist, but also draws on a Symbolist tradition from the 19th century. Like the Symbolists, Matisse’s world is slightly abstracted and suspended beyond time. He uses allegories and microcosms to suggest elaborate worlds of the imagination. The great simplification of figures and forms in Matisse’s work encourages viewers to read them as symbols. Conversely the great elaboration of pattern in his work helps trigger imaginative transformations, turning a simple everyday scene into a fantastic dreamscape.