Computers come into their own as characters in films and novels in the 1960s: the controlling, proselytizing Alpha 60 (Alphaville, 1965), the insecure, ingratiating and murderous HAL (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968), the gender-bending, joke-loving Mike/ Michelle (The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, 1966). In these stories from the mid-60s, the computer is linked to the central nervous system of a city, a space craft and a colony on the moon. The computer relays messages, regulates oxygen levels, plays chess, debates with reporters, and even delivers lectures in a university. A powerful figure who can operate in diverse situations, the computer is a compelling virtual character–not quite real as a personality, but real in its effect on others.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress is Robert Heinlein’s entertaining novel of a penal colony on the moon whose rebellion from Earth is abetted by a rogue computer. The polymorphous computer in the story is known as Mike for one user and as Michelle for another, changing identities and genders to suit all needs. A similar trend of sexual ambiguity appears in the fashion world at this time, with androgynous model Twiggy and rock chameleon David Bowie leading the way. The computer in Heinlein’s novel is also known as Adam Selene and Simon Jester. Selene is the Greek goddess of the moon, a fitting name for a character who controls space operations on Luna. Adam Selene is a pseudonym adopted by the computer to allow members of the colony to believe in a heroic, but unseen, leader of the revolution.

The gender-bending computer in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress reflects the androgynous fashions of the 1960s. Left: portrait of fashion model Twiggy by Christian Borau Pousa. Right: Pop artist Allen Jones challenges assumptions about sexuality in his hermaphrodite series in 1963.

The revolution gains momentum through small acts of social disruption and sabotage. When these symbolic acts occur, the computer credits them to Simon Jester to irritate and confuse authorities. Soon other rebels perpetrate their own acts of resistance in the name of Simon Jester. The tag goes viral and becomes symbolic of the resistance movement. The novel predicts the role of computers in spreading dissent and counter cultural ideas–an extraordinary anticipation of the power and possibilities of computer aided-communications in transforming society.

Themes of rebellion from authority and the expansion of consciousness are common to these works of the 1960s. What intrigues me is the way that computers are portrayed with human traits, neurosis, thoughts and needs, yet are also separated from humanity by their machine-like state. In an earlier post, I described how Isaac Asimov humanized computers by giving them flaws and conflicted motives. The computer stories of the 1960s go further by suggesting that the flaws of the computers are also flaws in a social order dependent on technology.

Alphaville: Cinematographer Raoul Coutard combines the feel of film noir with a cinéma vérité mobility, shooting Paris at night through glass, neon, reflected lights, and disorienting signs.

Alphaville, like other films of the French New Wave, daringly disregards the niceties of conventional narrative. It is violent and funny, bold and inventive. There are no futuristic sets or props. The night shooting features flashing lights and disorienting reflections. Hand-held cameras track actors through labyrinthine corridors in a treatment that is so stark and unrelenting that it conveys the idea of a strange and alien world.

The computer Alpha 60 is shown in a variety of ways stressing Godard’s Pop Art sensibility: as an ordinary stove top element, burning hot, or as a slowly rotating wall fan silhouetted against the light. Electricity and a cooling system are its essence. While the computer is rarely seen, its voice is frequent and omniscient, carrying through every hotel room, lobby, classroom and city street. Alpha-60 is instantly recognizable by it distinctive voice–spoken by a man with an artificial voice box–as it makes statements such as: “Nor is there in the so-called Capitalist world or Communist world , any malicious intent to suppress men through the power of ideology or materialism, but only the natural aim of all organizations to increase their rational structure.”

Alpha-60 is connected to all telecommunications systems in the city and also conducts seminars at the university. One interpretation of the film (David Anshen, 2007) is that the computer’s control of Alphaville is an allegory for Hollywood’s control of world cinema. Hollywood replaces thoughtful or idiosyncratic stories with formulaic doses of sex and violence. Anshen’s interpretation rests on the notion of a Culture Industry introduced by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer in 1944. Culture is prone to mass production like any other commodity. Mass culture is seductive, providing easy satisfactions which deceive people into thinking it is an accurate reflection of themselves, their needs and interests. Mass culture prevents any other kind of culture, any independent voice from being heard. In Alphaville, the computer (representing the Hollywood monolithic model) is defeated by a man who recites French poetry (the New Wave artists) and who baffles the computer by speaking in riddles, paradoxes and metaphors. Flashing light is a repeating motif throughout the film. Godard cleverly uses this light motif to signify both the artificial nighttime world of Alphaville and its control by an artificial intelligence and to signify the awakening of love through the influence of poetry.

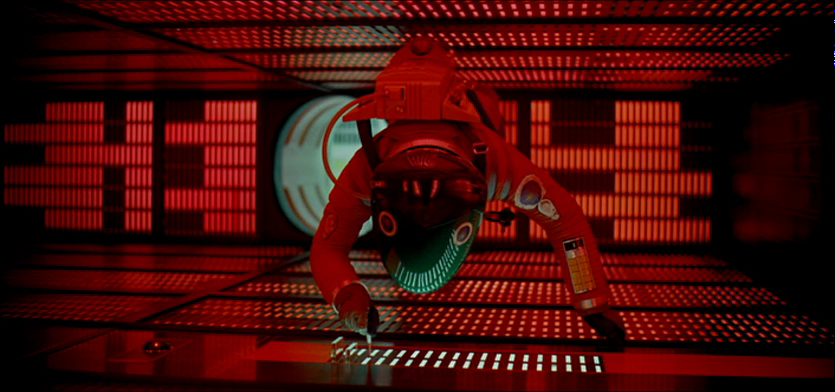

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL wants to fit in with the crew on the spaceship. The astronauts treat HAL more like a servant than an equal, though the computer’s intelligence far surpasses their own. The viewer sympathizes with HAL because of this disregard. However HAL’s hurt feelings quickly turn to paranoia. He over-reacts and begins harming the very crew he was designed to serve and protect. One of the great murder scenes in cinema involves the disconnection of HAL by the methodically determined astronaut David Bowman. The computer pleads for his life as his circuits are unplugged.

HAL regresses to his first memories, singing the children’s song “Daisy Bell”–an incident based on the first talking computer (the IBM 7094) programmed to sing a song in 1961. HAL’s childish regression is the inverse of the astronaut’s journey, which involves a rebirth into a higher form of consciousness.

As a story of future evolution, 2001: A Space Odyssey parallels Arthur C. Clarke’s earlier novel, Childhood End, 1953. In this novel, aliens come to Earth and impose a set of benevolent rules, which forbid warfare and the exploitation of others. The human race prospers under the guidance of the alien Overlords. However, a small community of people object to this paternalistic benevolence and rebel from it to start their own colony. The aliens have been waiting for this moment because it is only be rebelling, by taking ownership of their own actions, that people are able to evolve to the next step in the expansion of consciousness. In Space Odyssey, all needs are met by the computer so the astronauts do not have to think for themselves. It is only when they rebel from the computer that they begin on a path toward a more advanced and independent form of thinking.

The human relationship to the computer in Space Odyssey is symbolic of a dangerous loss of control of technology. HAL is portrayed as both a gentle male voice and as a round glass bulb with a glowing red light inside. There is some similarity between this glass light and the rounded astronaut’s helmut, the glass visor with its multiple reflections as dots of coloured light superimposed over the human face buried inside. But whereas the computer’s image is visually static, the human face through glass suggests vulnerability and courage in an encounter with the unknown.

After disengaging the computer, the astronaut travels through space, witnessing a cosmic light-show (with special effects by Douglas Trumbull). This awe-inspiring Stargate sequence suggests an hallucinogenic drug trip and serves as a tonic from the claustrophobic spaceship environment and the controlling, limited viewpoint of HAL.

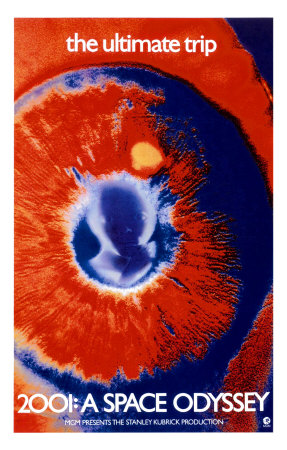

MGM’s revised ad campaign for 2001 featured the tag line, “The ultimate trip” to alter viewer’s expectations of the film.

Mike Kaplan, marketing executive with MGM, explains how the film confounded expectations of viewers at the time: “It was being presented as “an epic drama of adventure and exploration, and many were expecting a modern Flash Gordon. Instead, Kubrick had created a metaphysical drama encompassing evolution, reincarnation, the beauty of space, the terror of science, the mystery of mankind.” (The Guardian, November 2, 2007)

The revised marketing campaign related the film with psychedelic altered states, heralding a new approach to science fiction. The hallucinatory aspect of the film also signalled a new direction for later computer stories. In works such as Neuromancer (1984), Idoru (1996), Strange Days (1995), The Matrix (1999), computers are depicted not as super-logical machines, but as gateways to mind-bending environments and experiences. In the cyber-punk milieu, computers are depicted less as personalities and more as plug-ins enabling an interface with the human psyche, often presenting illusory projections. In these stories the distinction between what is natural and what is artificial breaks down. The distinction between hero and villain, oppressed and oppressive, also begins to blur. Cyberspace is inherently lawless. Unlike in Alphaville, where the computer represents order and reason, in later stories the computer is a site of uncontrollable energies where hallucinations, viruses, firewalls, hackers, and virtual characters intermingle and where reality and self-identity come into question.