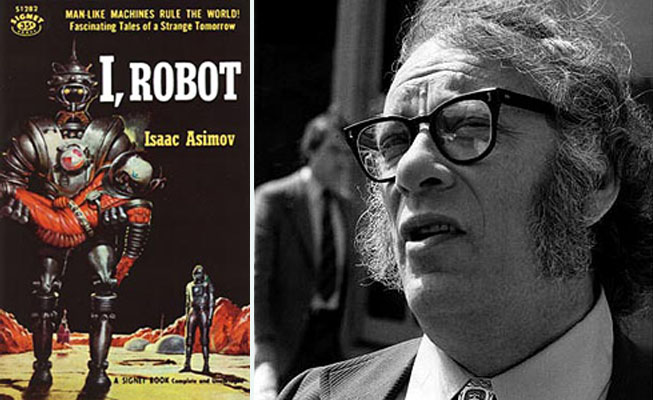

American polymath Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) was an author and educator who wrote nearly 500 books on topics ranging from physics and chemistry to Shakespeare and the Bible, though he is best known for his contributions to science fiction. In 1950, he combined nine previously published short stories into the groundbreaking collection I, Robot. Asimov moves away from the Frankenstein model that had characterized earlier robot stories by introducing self-aware machines governed by the Three Laws of Robotics. The three laws, hard-wired into every robot’s Positronic brain, are designed to protect humans from unexpected harm. However, there are special cases where the laws, which resemble Biblical injunctions for artificial life, cannot be followed without encountering paradoxes and ethical dilemmas. As the robots become conflicted in their motives and actions, they become more complex, more vulnerable, more human-like. The robots become so confused and troubled, at times, that they require a psychologist to understand them.

Actress Maxine Audley played Dr. Susan Calvin in a 1962 TV version of the Asimov story "Little Lost Robot".

The robot psychologist Dr. Susan Calvin is the central character framing each story. Calvin describes how at each stage of robot evolution there are puzzling kinks to be overcome. The robots develop symptoms of amnesia and hysteria, as well as being cunning, fraudulent, arrogant, escapist and given to practical jokes. A theme of loneliness and emotional insecurity runs throughout the collection. As an old woman looking back over her life, Calvin addresses a young man: “Then you don’t remember a world without robots. There was a time when humanity faced the universe alone and without a friend. Now he has creatures to help him; stronger creatures than himself, more faithful, more useful, and absolutely devoted to him. Mankind is no longer alone. Have you ever thought of it that way?” (p. xiv) This belief that machines can fill emotional voids in people’s lives is not altogether reassuring, but Asimov’s projected history of robots does make a convincing case that human dependency on machines will increase in a great variety of ways.

Workers set up the Futurama exhibit at the New York World's Fair in 1939, the same year Asimov sells his first SF short story . The hopeful future was a favourite Depression-era topic.

The first story, Robbie, concerns a girl whose nursemaid is a robot who she obsessively regards as her only friend, an obsession that alienates her from other possible playmates or sources of human connection. The situation parallels the way today’s children turn to computers and electronic games in a similarly absorbed fashion. In the story Liar, a mind-reading robot is so empathetic with people, so sensitive not to hurt fragile feelings and inflated egos, that the robot fabricates untrue but agreeable answers which lead to disastrous results. Asimov understands what people want may not be truth, but rather flattery, approval, and distraction from unpleasant problems. Robots can and will answer to these needs. But the robots in Asimov’s universe are also prone to seek approval and to find their own escapes from conflicted urges. In the story, Escape! the robot called The Brain, which is really a computer, finds a way out from an impossible situation by developing an extraordinary sense of humour. Sending two astronauts into a temporary death-like state, the Brain manipulates their thoughts with a bizarre sense of play. “Something broke loose and whirled in a blaze of flickering light and pain. It fell–

–and whirled

–and fell headlong

–into silence!

It was death!

It was a world of no motion and no sensation. A world of dim, unsensing consciousness; a consciousness of darkness and of silence and of formless struggle.

Most of all a consciousness of eternity.

He was a tiny white thread of ego–cold and afraid.

Then the words came, unctuous and sonorous, thundering over him in a foam of sound:

Does your coffin fit differently lately? Why not try Morbid M. Cadaver’s extensible caskets? They are scientifically designed to fit the natural curves of the body, and are enriched with Vitamin B. Use Cadaver’s caskets for comfort. Remember–you’re–going–to–be–dead–for–a–long–long–time!” (p. 197-198, Bantam, 2004 edition)

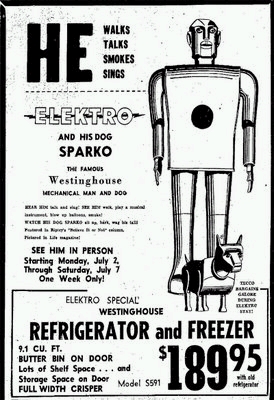

Robots sell products as well as books and films. The robot Electro and his dog Sparky, developed by Westinghouse, were such crowd favourites at the New York World's Fair in 1939 that they featured in ads as well.

Asimov invents a new genre for SF– the mystery comedy. In his book A Treasury of Humour, 1971, Asimov states his belief that humour derives from a sudden shift in perspective, moving unexpectedly from the sublime to the ridiculous. The stories in I, Robot alternate between cosmic practical jokes and face-saving acts of grace. The practical jokes serve to moderate the exaggerated self-esteem of a too-proud character–a necessary come-uppance. The acts of grace serve a reverse principle, as a broadening of understanding regarding the flaws of others. Flaws in character–whether human or robotic–could be described as the inadequate response to conflict–an unheroic path that encourages empathy rather than emulation on the part of the reader. Along with understanding conflicted feelings that cause mental turmoil, Asimov comically shifts the point of view so that this turmoil resolves or so that it does not seem so pressing, so anxiously all-important. In his other SF stories and novels, Asimov moves from the pathology of robots to what he calls psycho-history. History is marked by conflicts, by inadequate responses, mistakes, abuses and regret. Yet miraculously people move on. We do so because we learn to see the world in a different way. The paradigms shift and what was all-important and a cornerstone of belief for one generation becomes a mirage-like misconception for the next generation. Asimov is a futurologist, predicting patterns of change in technology and belief.

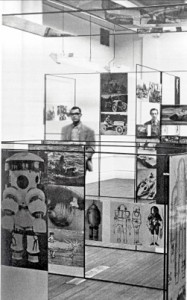

Written at a time when machines such as cars, television, washing machines and countless other devices were transforming all aspects of North American life, I, Robot explores a culture that depends on technology for its most basic services and communications. The collection appears between two important exhibitions, The New York World’s Fair, 1939, whose theme was “Dawn of a New Day–Tomorrow’s World,” and the “This Is Tomorrow” art exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, England, sponsored by the art collective, The Independent Group, in 1956. The former was a commercial tourist-oriented affair dreamed up in the midst of the Depression to boost morale and stimulate spending. The latter was a meeting ground of fine art and popular culture in an optimistic postwar atmosphere in which plentiful goods and increased leisure were hopeful signs of a breakdown of class barriers. Both exhibitions featured robots in key exhibits. In New York, Westinghouse unveiled the 7- foot-tall Electro and his robotic dog, Sparky, a promotion suggesting their own electric home appliances, like robots, would free households from unwanted drudgery. The London exhibit, staged 17 years later, featured Robby the robot from the Hollywood film Forbidden Planet, 1956. Robby was designed by Japanese-American engineer Robert Kinoshita and built by the MGM prop department, at a cost of $125,000. In the fine art world at this time, the robot was a symbol of trashy movies and unsophisticated tastes. This was also a prejudice that Asimov and his editor John W. Campbell would strive to overcome, as they defined a new brand of science fiction aimed at adults , featuring stories in which technology is presented not as a gimmick-like prop but as an integral and inevitable aspect of any future environment.

This is Tomorrow exhibition, Whitechapel Gallery, 1956 marked the beginnings of British Pop Art, a movement which American artists emulated in a more cynical and ironic manner.

Asimov’s collection of robot stories ends with a robot who enters politics and wins one election after another. Machines begin running the world simply because they can make better decisions than people can. The final story, The Evitable Conflict, (that is, the end of conflict), argues the machine take-over will not be the fanciful, violent revolution of R.U.R., nor will it be malevolent and self-serving, as in The Matrix. Rather, the machine/ computer revolution will be silent, invisible, and without overt struggle. This change will come about because it is advantageous to people dependent on machines for their survival as they live in ever-denser populations in ever-more complex interactions with one another. As computers replace not only workers, but managers and strategists as well, they promote the comforting belief that people are in control of their own fate. This belief is fostered by periodic break-downs in the system and by a constant set of adjustments and counter-measures. Machines, Asimov argues, even if they could plan and operate perfectly, would chose not to do so. Instead, machines would introduce flaws to give room for human hopes, as an final act of face-saving grace to fragile human egos. Asimov leaves his psychologist Susan Calvin with the insight that it does not matter if a belief is true or not, as long as it is useful.

I end this post on Asimov with a quick reference to Asimo, the humanoid robot built by the car manufacturer Honda in the year 2000. Standing 4 feet 3 inches tall, Asimo can walk, run and navigate stairs. He is the star of several TV commercials and when I watch one, such as the commercial below, the last thing I think is that Asimo needs a therapist.