The automaton is a life-like doll or mannequin that moves by means of hidden gears. A precursor to the robot, the auto-maton is a one-of-a-kind marvel used to amuse large audiences with simple tricks. In contrast, the robot is a product–and symbol–of mass production and the culture that depends on assembly lines and standardized parts. The best-known promoters of automatons were clockmakers, inventors, illusionists, magicians–Maillardet, Maelzel, Robert-Houdin–men of the 18th and 19th century who wowed prince and public alike with their ingenious mechanical toys. It comes as no surprise to learn that silent cinema pioneer Georges Méliès was a collector of automatons, using deceptive moving props to augment his repertoire of cinema tricks. More surprising is to learn that Enlightenment philosopher René Descartes, social reformer and novelist Charles Dickens and inventor Thomas Edison also experimented with mechanical figures. (Gaby Wood, Living Dolls, 2002) Mary Shelley wrote the story Frankenstein, 1818, two years after seeing Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s writing automaton in the watch-making district of Neuchatel, Switzerland. Shelley’s father, William Godwin capitalized on his daughter’s success by writing Lives of the Necromancers, 1834, a legendary history of artificial life.

A charming example of a working automaton is “The Draughtsman-Writer,” created by the Swiss-born, London-based clockmaker and inventor, Henri Maillardet (1745-?). Badly damaged when it was donated to the Franklin Institute of Science in Philadelphia in 1828, the automaton was mistakenly attributed to Johann Maelzel, a man infamous for his fraudulent chess-playing machine, (Edgar Allan Poe published an exposé on this subject, giving some sense of the fascination and popular appeal of these automata in 1836). A staff mechanic at the Franklin Institute was able to get the the Draughtsman-Writer

working. Wound up, the automaton produced 4 drawings and 3 poems, one of which boasted how he was beloved by women all over the world and even by their husbands, then concluded: “Écrit par l’automate de Maillardet,” revealing the true identity of the inventor.

The automaton’s poems and drawings are designed to answer questions from the audience, such as “What does the future hold for me?” or “What am I thinking?” One drawing shows a cupid with bow and arrow, another shows a sailing ship. As portents of the future, love and a journey, are agreeable messages. The automaton is not just a mechanical wonder, it is also a fortune teller and a mind-reader. In his essay, The Uncanny, 1919, Sigmund Freud writes at length about automata as examples of things that produce an uncanny effect. Freud’s definition of uncanny involves a fearful feeling toward something that is simultaneously perceived to be familiar, yet strange and disturbing. Freud develops this into a theory of how the unconscious returns suppressed mental impressions in an altered guise. Reactions to the automaton, Freud suggests, touch on our own ambivalent attitudes toward life ad death.

As a figure in art, the automaton represents a blurring of boundaries between animate and inanimate things. In a painting or a work of literature, a doll can be as life-like as a person. Artists can also portray people as mechanical and unfeeling. Art allows the viewer to perceive this humanizing and dehumanizing process at work.

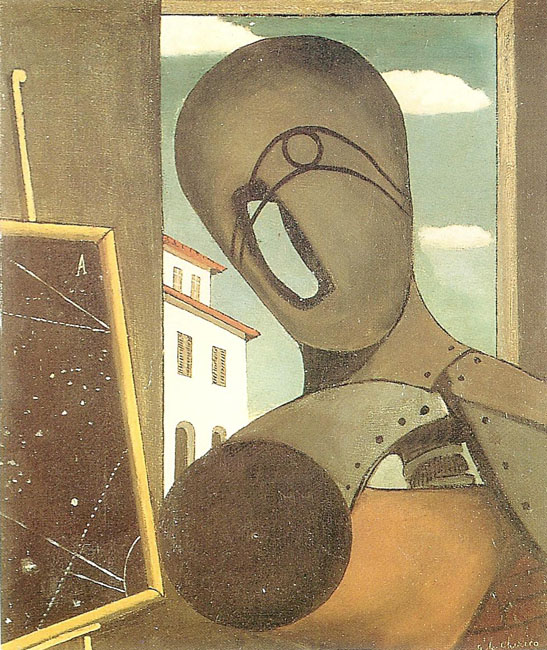

An artist celebrated for exploring the automaton theme was Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978). de Chirico was a Greek-born painter of Italian parents who travelled widely throughout Europe. His classical training was broadened by encounters with German philosophy, Symbolist painting and Cubism. de Chirico merged these diverse sources into melancholic pictures of deserted squares, often depicted in late afternoon light with long shadows. These paintings convey a dream-like sense of dislocation, where odd juxtapositions of unexplained objects, such as classical arcades, train stations, statues and modern mannequins, drawing instruments, easels, maps and scientific diagrams anticipate the surrealist encounter. In her introduction to Metaphysical Art, 1971, Caroline Tisdale notes how many philosophers and artists share a mistrust of physical appearances as an explanation of reality. The philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer observed how people become complacent surrounded by familiar things and this complacency stunts imagination. As an counter measure, Schopenhauer encouraged original thinking through a process of estrangement. One strategy of estrangement Schopenhauer suggests is “to place monuments on low plinths so that they appear to walk among men.” (Tisdale, p. 9) The work of de Chirico, with its mannequin cities, fosters a similar feeling of estrangement. Art historian Wieland Schmied compares de Chirico’s figure of a jointed doll without a face to a blind but wise prophet: “Don’t we associate these figures with the idea of ‘inward vision’ or prophetic ‘second sight,’ precisely on account of the blindness that prevents them from seeing the existing world?” (Giorgio de Chirico: The Endless Journey, 2002, p. 61) Schmied goes on to describe the automaton in de Chirico’s work as an alter-ego, a doll artist. While similar visionary automatons appear in comic dramas written by the poet Apollonaire, a friend and early promoter of de Chirico, and Alberto Savinio, de Chirico’s brother, Schmied’s argument misses the satirical impact of a mannequin as thinker staring blankly at a complex diagram of the universe. Our new artificial selves are no more capable of understanding reality than our old physical selves were.

De Chirico suggests that classical statues and public monuments, which once represented community values in the guise of an ancestral hero or mythic goddess, have become obsolete in the modern age, replaced by mass-produced mannequins in shop windows. The mannequins are rootless and exhibit a plastic adaptability to different situations: they become the new comic heroes of absurd coincidence and irrational encounters.

To many artists, the automaton, with its hidden inner workings, recalled the operation of the unconscious. The term Automatisme was adopted by the Surrealists in the 1920s and by abstract painters in Quebec in the 1950s. Influenced by psychoanalysis and by Sigmund Freud’s use of free association techniques, artists were intrigued by the possibility of creating work that escaped the censorship of the conscious mind. By making art that defied rational principles, the surrealists hoped to bait, antagonize and expose the hypocrisy of the bourgeois. Automatiste painting proudly asserted a connection to an authentic inner world, unhampered by artificial social barriers and conventions. This claim of authenticity would later be disputed by postmodern critics, who countered that all art, like language, is mediated by convention. This is criticism in hindsight. In the repressive Duplessis era in Québec, before the “silent revolution” of the 1960s, Automatisme served an important function, infusing creative energy via abstract art into an otherwise parochial art scene. For Paul-Émile Borduas, author of the revolutionary manifesto, Refus global, 1948, and leader of the Québec-based Automatistes, Automatisme was a move away from imitating foreign styles as Canadian artists had done in the past. Instead Borduas urged his fellow artists to be as innovative and inventive as leading artists elsewhere and to pioneer new ways of seeing of their own. For this, Borduas is celebrated as one of the most inspiring and liberating figures in Canadian art.