Norman McLaren directing Neighbours, 1952. photo by Evelyn Lambart

Norman McLaren (1914-1987) is a pioneer film animator, famous for drawing both picture and soundtrack directly on film and for mixing together live action with animated effects. His work is experimental, yet conveys a remarkable sense of charm, humour and popular appeal. Like his mentor John Grierson, McLaren was born in Stirling, Scotland. The son of an interior decorator, McLaren studied at the Glasgow School of Art from 1932 to 1937, but did not graduate. He was absorbed by his early film experiments and left Scotland to work for the film unit of the General Post Office in London.

During WW II, Grierson convinced McLaren to come to Canada to work for the National Film Board, promising the young artist he would not have to engage in war propaganda. McLaren quickly settled into the NFB, establishing an animation department in 1941 and creating such ingenious and diverse works as Neighbours, 1952 (Academy Award winner); Blinkity Blank, 1955 (winner of Palme d’or, Cannes) ; Le Merle, 1958; Canon, 1965; Pas de Deux, 1965; and the five-part instructional film, Animated Motion, 1976-8. McLaren used an extreme economy of means to achieve sophisticated effects that have a powerful visceral effect on viewers. His work brings together interests in abstract imagery, drawing games, folklore, music, performance and education.

Opening Speech

This above clip is a mash-up of two works, Opening Speech, 1961, directed by Norman McLaren, and A Chairy Tale, 1957, directed by Claude Jutra and McLaren. McLaren and Jutra are two of Canada’s greatest film directors, and in this sequence the directors perform in their own films. Both use the stop motion technique to explore the theme of a man struggling with an uncooperative object. This mash-up is meant as a tribute to the charm and inventiveness of two great talents, edited by contemporary artist NV. A new soundtrack featuring the Charlie Parker Quintet has been added. The music dates from the period when the films were made, and, like the films, combines innovation with entertainment.

In 1961, McLaren made Opening Speech: Norman McLaren, putting his name in the title, as well as starring in the film. The project moves away from McLaren’s abstract painting-inspired experiments (Dots, Begone Dull Care) toward performance-based, multi-media work that is also an important trend in the Fine Arts at this time. In the film, McLaren commands a large empty stage, from which he is about to make a formal speech, but the filmmaker becomes lost in his notes, the first of many difficulties for the reluctant public speaker. This reflects a famous anecdote McLaren tells about presenting a script and storyboard to producer Alberto Cavalcanti at the General Post Office Film Unit in London, only to have Cavalcanti tear it up with the advice to, “Never write down everything precisely in advance.” (Derek Elley, “Rhythm & Truths,” Films & Filming, June 1974).

If words on paper do not make a film, then what does? Sound and image, performance and technology. In McLaren’s film, the performance and technology are clearly at odds as the microphone quickly develops a mind of its own. The sound goes out of sync with the picture. The microphone then rebels in other ways. The viewer is reminded that film is a form of technology, but technology, like inspiration or creativity, can never be fully controlled.

The animator was also an accomplished artist. Norman McLaren. Women Studying Optical Construction, 1964

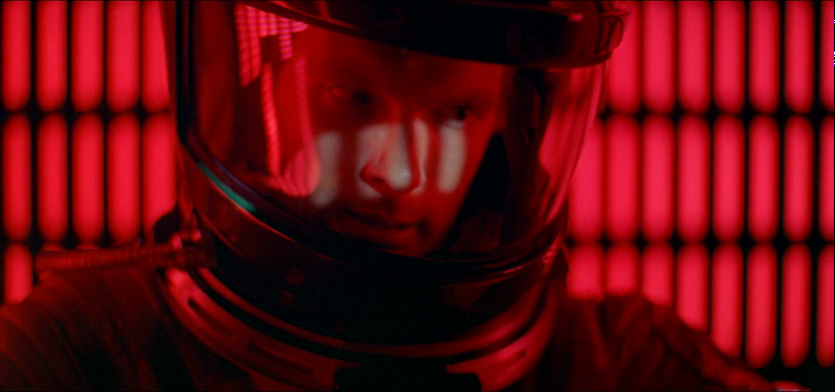

There is another consequence of this rebellious microphone: a potentially stuffy speech is turned into a humorous game. It might be helpful here to compare the microphone in Opening Speech to HAL, the computer in 2001: A Space Odyssey, made by Stanley Kubrick seven years later. Both films are about machines that function like living entities with their own personalities and agendas. But if the machines have minds of their own, the minds are out-of-harmony, spiteful, devious. In both films, a malfunction occurs at the worst possible time. The errant microphone disrupts a public statement by a famous artist, drawing attention away from the artist onto itself. The microphone’s antics render the artist mute, and turns the honor of the moment into a public embarrassment. It hijacks the event, the opening of a film festival, just as HAL hijacks the space mission in 2001. In order for the space mission and the film festival to get back on track, the obstructing machines must be murdered. Once this murder occurs, both films then unveil a screen and a pre-recorded message—on film—appears and restores order.

Paranoia

Opening Speech and 2001 mix humour and paranoia together in their handling of delinquent machines. Novelist Philip K. Dick, an authority when it comes to delinquent machines, commented: “The ultimate in paranoia is not when everyone is against you, but when everything is against you. Instead of ‘My boss is plotting against me,’ it would be ‘My boss’s phone is plotting against me.’ Objects sometimes seem to possess a will of their own anyhow, to the normal mind; they don’t do what they’re supposed to do, they get in the way. They show an unnatural resistance to change.” (quoted in Carl Freedman, Science Fiction Studies, March 1984)

Paranoia involves a projection of fears, mixed with feelings of self-love and self-hate. These are the two facets of paranoia remarked on by Freud, “self-aggrandisement” and “persecution by an imaginary enemy.” (The Schreber Case, 1911) Elements of aggrandisement and persecution are present in Opening Speech. The public speech inflates the speaker’s ego and the rebellious microphone punishes him without apparent cause. Since no audience is ever seen, McLaren’s stage antics become somewhat imaginary. It is as if he were performing for himself or as if the fame and frustration of the moment are all in his head.

In contrast, it is not the astronaut but the machine who becomes paranoid in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The machine’s fears reflect a personality weakness in an otherwise seemingly flawless system. This weakness makes the machine appear psychotic, but in a human-like way, as it faces the prospect of being deactivated and removed from the mission.

Opening Speech could be described as a meta-discourse on film. It demonstrates how cinema manipulates time and space, as well as disrupting our sense of reality. Opening Speech ends by directly quoting two famous silent films, Sherlock, Jr. by Buster Keaton and Entr’acte by René Clair, both made in 1924. In the scene in question, McLaren jumps into the cinema screen, then steps out again, shattering the words, “The End.” In these film, figures move forwards and backwards in time to disrupt the viewer’s sense of reality. All three films raise the question: is cinema real? And, if not, what is reality?

Opening Speech draws heavily on vaudeville, but it also looks ahead to key moments in Canadian visual art. In one of artist Janet Cardiff’s best known audio installations, The Missing Voice, 1999, the recorded audio guide accompanies the viewer through a tour of Whitechapel Library in London, commenting on work within the space. However, the guide begins making unpredictable remarks that lead the viewer away from the intended experience to other points of interest, shattering accepted conventions in an unnerving about-face generated by a willful mechanical device.