Two dream worlds collide, advertising and science fiction. Both create alternate universes, selling a future transformed by time-saving gadgets and by the flash and wonder of new technology. Ads conjure up optimistic utopias; SF is drawn to problematic dystopias. Ads try to manipulate and shape public thought and behavior, a major theme of SF. Advertising imagery pervades SF, from George Orwell’s sinister posters of Big Brother to the mock commercials which colour the hallucinatory world of Philip K. Dick.

In Dick’s stories, inane objects serve as the outward face of hidden, disturbing conspiracies. In the 1964 novel, The Simulacra, a character speculates that even in outer space, explorers will have to fight their way through a glut of consumer products. “We’re being robbed, he decided. The next layer down will be comic books, contraceptives, empty Coke bottles. But they–the authorities– won’t tell us. Who wants to find out that the entire solar system has been exposed to Coca-Cola over a period of two million years?” (The Simulacra, p. 40) In the novel Ubik, ads serve as chapter epigraphs. Ubik is an ever-present, ever-changing product. At times it’s a car, then a brand of beer, then a type of instant coffee. Ubik finally appears in the story itself as an aerosol spray can which allows its users to escape disappearing into a death-like state of unreality. Literary critic Carl Freedman comments: “In the end, this strange but paradigmatic commodity is identified with theological mystery: ‘I am Ubik. Before the universe was, I am … I am. I shall always be.” (“Towards a Theory of Paranoia: The Science Fiction of Philip K. Dick, SF Studies, March 1984, p. 21) In the discussion that follows, I focus on two novels: The Space Merchants, 1953 by American novelists Frederik Pohl and Cyril M. Kornbluth, and Pattern Recognition, 2003 by Canadian novelist William Gibson.

The Space Merchants, first published in 1953. This 1974 Penguin edition cover by David Pelham captures its proto-Pop spirit.

The Space Merchants is set one hundred years in the future, but feels strangely like a period novel of the consumer-driven 1950s. In the novel, rival advertising firms declare war on one another in their ruthless quest to control the Venus account. Venus invites unlimited exploitation but involves selling an unsellable product–the colonization of a distant planet with its unbreathable waterless environment, hurricane winds and terrible heat. This does not deter ambitious copywriter, Mitchell Courtenay, of Fowler Schocken Associates, from taking charge of the project. However, Schocken’s control of the coveted account stirs up a hornet’s nest of corporate crime, as double agents, kidnappings, identity theft and murder run riot in this satirical and fast-paced novel. Adding to Mitchell’s woes is the activities of an underground conservation movement, the Consies, whose take on reality is jarringly at odds with that of Madison Avenue. The novel is full of fantastic plot twists and adopts an irreverent attitude to everything from the things we eat to the power of the president. Its wry take on the role of media in shaping popular culture makes it a dazzling proto-Pop novel.

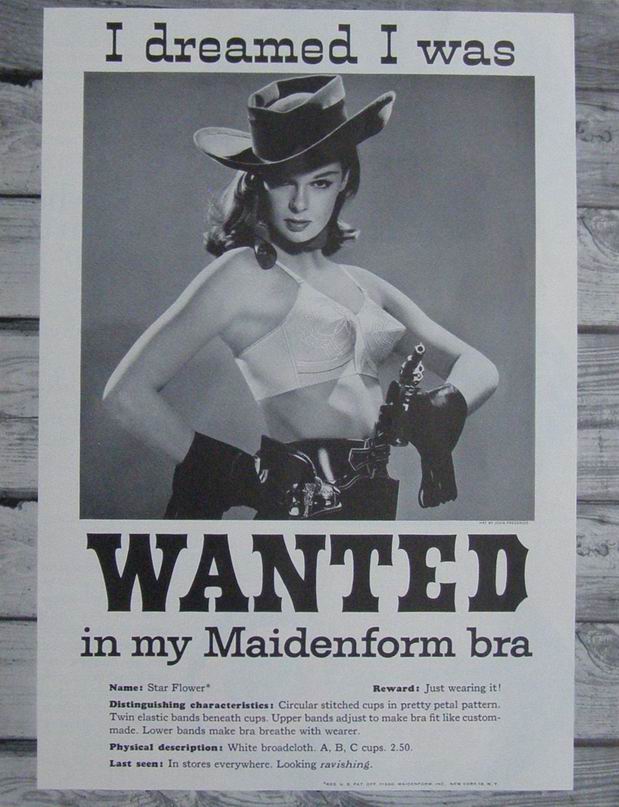

A Maidenform bra ad from the mid-1950s uses provocative sexual innuendo to sell women on the idea of appealing to men.

A key feature of Pop art is its appropriation of popular culture and methods of mass reproduction into the realm of high art. Pop Art focuses on crass and mundane subjects which appear as threatening intrusions when inserted into fine art settings. As one example of this Pop sensibility, the anti-hero of The Space Merchants meets a group of conspirators in a unlikely place–the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Inside the hallowed museum, the ad man notes the current show, a retrospective exhibition of the Maidenform bra campaign of the 1950s. The idea that bra ads would hang on gallery walls as art may have played as satire at the time, but today, as the field of art history merges with the wider interests of visual cultural, it seems eerily prescient. In a recent interview Pohl stated: “The science fiction method is dissection and reconstruction. You look at the world around you, and you take it apart into all its components. Then you take some of those components, throw them away, and plug in different ones, start it up and see what happens.” (Interview with Frederik Pohl, Locus Magazine, October 2000) In his later Hugo Award winning-novel, Gateway, 1977, Pohl takes this Pop approach one step further by supplementing a conventional narrative with a series of fictitious ads, memos and news bulletins that appear concurrent to the story, adding texture and widening the reader’s perspective.

Frederick Pohl first expressed his SF interests by contributing to fanzines and joining the Futurians club while still a teenager in New York city. He currently writes an informative “The Way the Future Blogs” with many reminiscences of old collaborators such as Kornbluth. Both he and Kornbluth were veterns of World War II, a war in which rocket technology was no longer a distant fantasy.

During World War II, the German aerial attack of London used V-2 rockets, creating the fear that no target was out of reach. After the war, the Americans invited Germany’s preeminent rocket scientist Wernher von Braun to come to the USA to turn this technology toward scientific purposes.

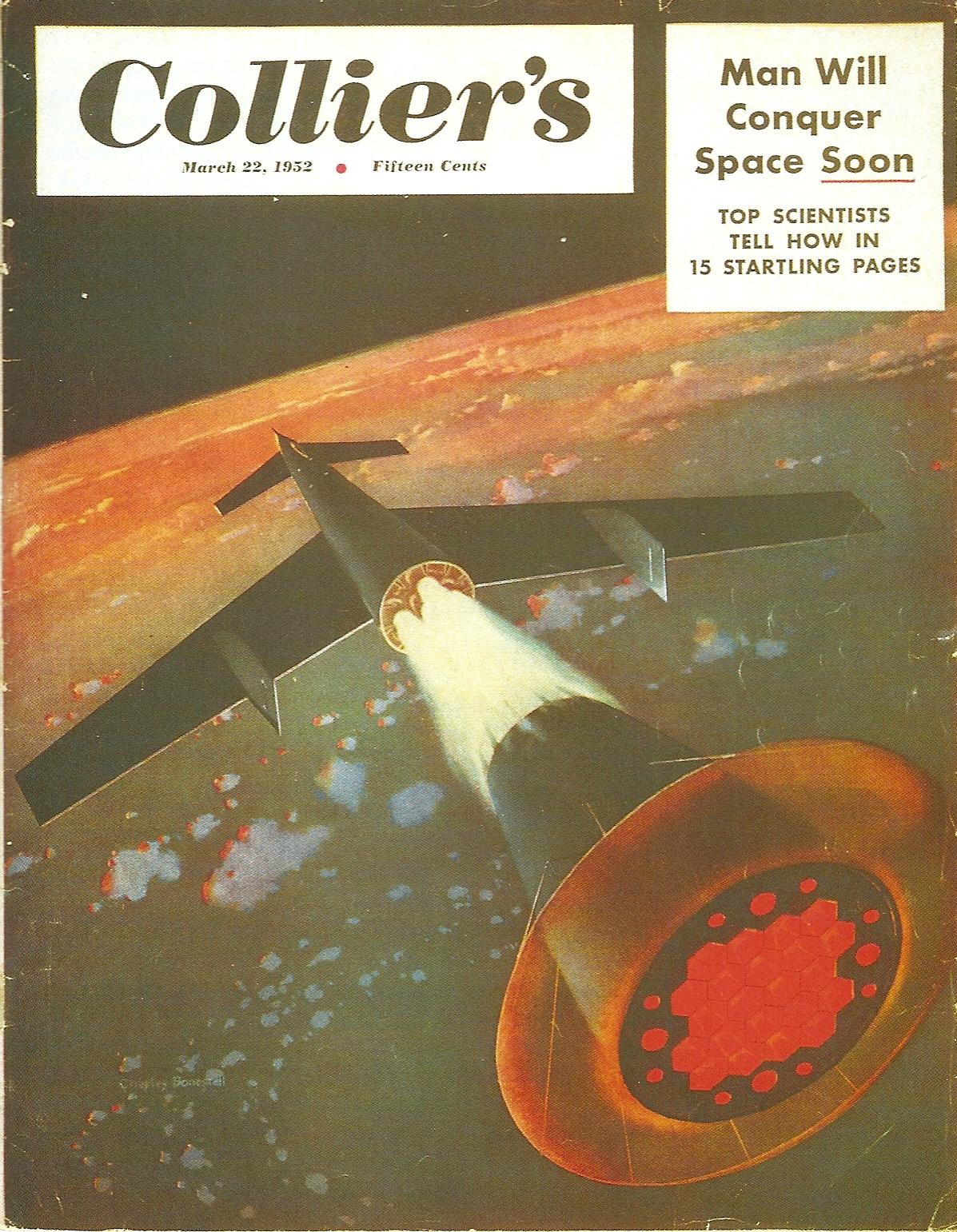

Popular magazines such as Collier’s helped spread the idea of technology transforming the post-war world. However, it was the Soviet launch of the satelite Sputnik that accelerated serious American investment in space ventures. Washington Post reporter Joel Achenbach recalls how “Americans reacted to the {Russian] satellite, which could be seen in the night sky, with a mixture of fascination and dread.” During the Space Race that ensued, von Braun was instrumental in creating the Saturn V booster rocket which enabled the first astronauts to land on the moon in 1969. But the lasting legacy of these rockets, was not in outer space, but in the technology that satellites have allowed to flourish here on earth such as cell phones and other forms of instant wireless communication.

The 3-D glasses craze was an attempt by movie theatres in the 1950s to offset the competition of television.

The Space Merchants consistently links technology with communications, introducing inventions such as multi-sense films. I’m reminded of how cinemascope and 3D films were introduced in the 1950s in Hollywood’s bid to compete with the rapid spread of TV. Pohl and Kornbluth introduce fantastic inventions–bio-engineered foods and ads appearing on the windows of public vehicles–which have almost come to pass in today’s world of industrial farming and omniscient digital screens. In the novel, the product coffiest “contains three milligrams of a simple alkaloid. Nothing harmful. But definitely habit-forming. After ten weeks, the customer is booked for life.” (The Space Merchants, p. 10) The story’s ad agencies introduce their products to children, imprinting lifestyle patterns at the most impressionable age. The authors foresee these products promoted by multi-national corporations, operating across the globe as powerful forces more influential than governments. At the same time the authors cannot resist inserting nationalist rhetoric, as Americans justify their need to wield exclusive control of space colonies in order to protect American interests.

On his blog, Writing Scraps, Sean J. Jordan reviews the novel. Joradn ehthuses: “What makes this book so awesome is the world that Pohl and Kornbluth conceived. It’s frighteningly close to the world we live in today. Advertising is used not just as a means of persuading people to buy products, but to shape public opinion about real issues, like the scarcity of water and fuel, and to make people feel like their lives are better than they really are. Every piece of communication is persuasive; every idea has an agenda. Even the simplest slogan has been massaged by expert ad men. The world is a dark and frightening place, and yet society is kept under control by these resassuring messages that they should be happy because of the products they consume. One of the most memorable and horrifying scenes in the book comes when Courtenay finds his way into the facility where “Chicken Little,” a processed chicken product, is packaged. What he finds is a giant, living mound of chicken tissue, where butchers come and cut pieces of flesh off to prepare for processing and packaging. The campaign around the product leads you to believe you’re eating normal chicken, but this genetically engineered, unthinking living blob of meat is all it is. The idea is that as long as people don’t know what they’re really eating, society will hold together.” (review 19 July 2009)

On his blog, The Zone, Patrick Hudson comments: “The 1950s was a great era for these acid observations on the capitalist system. Authors such as Kurt Vonnegut, Robert Sheckley, Bob Shaw, Harry Harrison, Jack Vance, and Pohl and Kornbluth filled the gap between the gee-whiz optimism of the pulp era and the more radical politics of later eras with great style and wit, as exemplified in The Space Merchants.”

The novel’s irony revolves around the hero’s stubborn inability to see how upside down his values are and as a result he consistently harms the things he should value most, including the woman he loves and the environment. He believes he can win the woman’s love by succeeding in his career. However the ruthless steps he takes to achieve this success horrify the woman, who serves as a conscience figure throughout the story. The ad men regard the environment as a disposable resource. Fowler Shocken outlines the history of advertising, “from the simple hand-maiden task of selling already manufactured goods to its present role of creating industries and redesigning a world’s folkways to meet the needs of commerce.” (p. 12) “The world is our oyster,” Shocken boats. “We’ve made it come true. But we’ve eaten that oyster.” Now they look for new worlds to conquer, to repeat their pattern of exploitation and disposal.

The novel introduces a new kind of hero into American literature–the cynical ad man, who uses “statistics, evasions and exaggerations” as a sure-fired path to power. Ads invite conformity to a pushy sales pitch, but the ad men see themselves not as conformists but as resourceful adventurers. On her blog Mediaknowall, media historian Karina Wilson writes: “By the 1950s, advertising was considered a profession in its own right, not just the remit of failed newspapermen or poets. It attracted both men and women who wanted the thrill of using their creativity to make some serious cash. Hard-working (early heart attacks were common), hard drinking (those legendary three martini lunches), unconventional and often amoral, the flannel-suited Ad Man became a recognisable archetype, the epitome of a new kind of cool.”

The Space Merchants recognizes that both corporations and conservationists use various forms of public messages to rally people to their causes. Propaganda can be used for constructive as well as harmful purposes. After a sudden reversal of fortune, the cynical ad man in the story joins forces with the conversation movement. To rise within their organization, to make himself indispensable to the environmentalist cause, Courtenay rewrites their communiqués and launches campaigns questioning the corporate control of basic services. The ad man doesn’t for a minute believe in what he is doing, but his methods are effective. He has no money to promote this counter narrative, so he resorts to spreading rumours and using viral messages. The use of viral messages is a major theme of the second novel I’d like to discuss, Pattern Recognition.

In this story, an underground filmmaker has invented a brilliant new synthesis of computer animation and live-action film, samples of which are released in fragments on the Internet, with no supporting texts or documents. The identity of the filmmaker is a mystery, as is the shape, content and intention of “The Footage.” An Internet discussion group, FFF—Footage Fetish Forum–a reference to www, the Worldwide Web, has sprung up to share information about this inspiring but obscure material. Wealthy advertising executive, Hubertus Bigend, is obsessed with exploiting new trends and finances a search for the artist behind the Footage. He hires as a

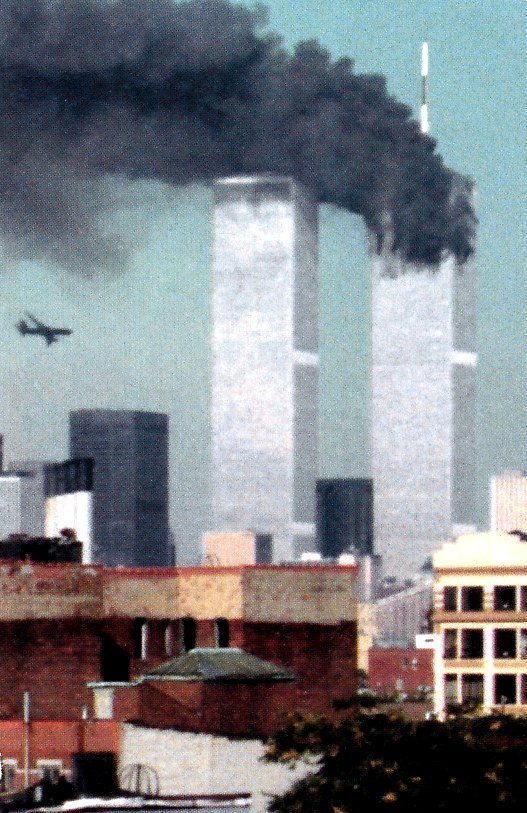

The anxious mood in the aftermath following attacks on the twin trade towers in New York, 2001, underlies the novel Pattern Recognition.

detective the young design consultant Cayce Pollard. Pollard identifies closely with the figure behind the Footage. Her mission, which takes her to cities around the world and introduces her to a rogue’s nest of traders, collectors, spies and computer fanatics, becomes increasingly personal. Cayce uses the Footage to exorcize a series of traumatic ghosts, such as her grief for her absent father, missing since the attack on the World Trade Towers on September 11, 2001. As Cayce moves closer to her goal of meeting the maker of the Footage, she realizes how she is fatally compromising something beautiful and worth protecting.

One of Gibson’s contributions to the SF genre is achieved by setting his disorienting stories in the present or near-future. He explained this at the book fair Expo America in 2010, reprinted in his latest collection of essays, Distrust that Particular Flavour, 2012: “I found the material of the actual 21th century richer, stranger, more multiplex than any imaginary 21th century could ever have been. And it could be unpacked with the toolkit of science fiction. I don’t really see how it can be unpacked otherwise, as so much of it is utterly akin to science fiction, complete with a workaday level of cognitive dissonance we now take utterly for granted.” As Lisa Zeidner in her NY Times review of Pattern Recognition put it: “Predicting the future, Gibson has always maintained, is mostly a matter of managing not to blink as you witness the present.” (NY Times, 19 Jan, 2003)

This MTV ad, 2002, suggests that broadcasting signals enter directly into the head of consumers in a techno-human fusion.

The Space Merchants and Pattern Recognition differ in their attitudes toward originality. The ad men in the 1950s novel are suspicious of unorthodox thinkers; the ad men and women in the 2003 novel embrace radical new ideas as the most marketable commodities there are. Cayce, like Courtenay in Space Merchants, is both insider and outsider. However Cayce’s loyalties are more complex and shaded. Whereas the ad men of the 1950s assert top-down pronouncements on the latest styles and trends, one style being good for everyone, the 21st century cool hunter is a more nuanced observer of a diffuse, constantly shifting scene. As a cool hunter, Cayce has an exceptional talent for spotting trends, for predicting which designs, which loogos, which products will ignite public interest. As a result, she is given considerable freedom to explore the random pathways of pop culture by the innovative ad firm, Blue Ant. Cayce pays a price for her talent. She is afflicted with a nausea-inducing nervous reaction whenever she comes in contact with too much branding.

Reviewer Lisa Zeidner shrewdly notes that “Gibson himself has always been something of a coolhunter, and Pattern Recognition gives Cayce his own sharp, wry eye. Her effortless hyperintelligence ought to put to rest any complaints that science fiction’s computer cowboys are members of an all-boys’ club. With such a tour guide, you don’t skip the descriptions.” (review, NY Times, 19 Jan. 2003)

The savvy imaging of pop culture. "Pink is still the new black according to Canadian pop princess Avril Lavigne, whose stage was candy coated like a giant Pepto-Bismol ad. On tour in support of her most recent album The Best Damn Thing, we discovered a different, brighter more poppy skater girl." (Review of Montreal concert from CornerShop Studios, April 8, 2008)

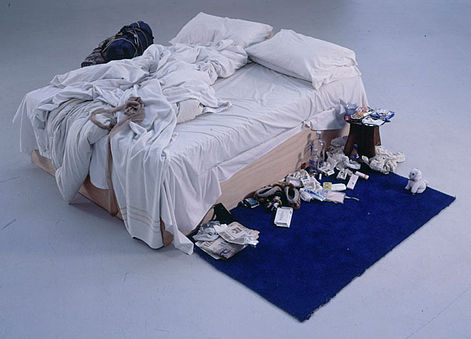

Young British Artists were promoted by ad man/ art magus Charles Saatchi. Shown here is an autobiographical work by Tracey Emin, My Bed, 1999.

Artists play a prominent role in Gibson’s novels. In Pattern Recognition, avant-garde art crosses paths with advertising and speculative capitalism, causing moral boundaries to blur. The fictitious Blue Ant agency has parallels to the real-life figure of Charles Saatchi. A British ad man who helped bring Margaret Thatcher to power with his scathing “Labour Isn’t Working” campaign in 1979, Charles Saatchi is also a keen art collector who opened the Saatchi Gallery in London in 1985 and immediately altered the landscape of contemporary art. His sponsorship of the school of Young British Artists assured such artists as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin wide public exposure and fabulous wealth. The novel Pattern Recognition compares ad man Hubertus Bigend to Saatchi (Pattern Recognition, p. 83). Hubertus explains his working methods to Cayce Pollard, his reluctant protégé. “‘The client and I engage in a dialogue. A path emerges. It isn’t about the imposition of creative will.’ He’s looking at her [Cayce] very seriously now, and to her embarrassment she feels herself shiver. She hopes he doesn’t notice. If Bigend can convince himself that he doesn’t impose his will on others, he must be capable of convincing himself of anything. ‘It’s about contingency. I help the client go where things are already going.” (Pattern Recognition, p. 64) Hubertus calls this pattern recognition, which in his mind means making money by recognizing and exploiting a trend before it explodes in the popular consciousness. As Hubertus puts it: “I want to make the public aware of something they don’t quite yet know that they know–or have them feel that way.” (p. 65)

The Footage represents a new trend, but what exactly is that trend? As an art form, The Footage remixes film clips downloaded or appropriated from other sources, then blends these stolen clips seamlessly together through computer animation and ingenious editing to create a new work. In the digital age, anyone can do this. Art is no longer the preserve of an elite few. Young people especially feel a need to participate in the things they see, to put their own stamp on it and to share it with their friends, encouraging others to do likewise. Hubertus describes the new thinking about art like this: “Musicians, today, if they’re clever, put new compositions out on the web like pies set to cool on a window ledge and wait for other people to anonymously rework them. Ten will be all wrong, but the eleventh may be genius. And free. It’s as though the creative process is no longer contained within an individual skull, if indeed it ever was. Everything, today, is to some extent the reflection of something else.” (p. 70)

The remix society, supported by an around-the-world-in-30-seconds, poverty jet-set, sparks new dislocations. Reviewer Lisa Zeidner comments: “Distant cities seem both strange and familiar, especially under the influence of jet lag, here also called ‘soul-delay.’ Culture itself, Gibson suggests, is a kind of jet lag, or, as Cayce’s therapist puts it, ‘liminal’ — a ‘word for certain states: thresholds, zones of transition’ … Cayce’s globe-trotting gives Pattern Recognition its exultant, James Bond-ish edge. Yet the book also manages to be, in the fullest traditional sense, a novel of consciousness — less science fiction than Henry James. After all, Oedipa Maas, the truth seeker of Lot 49, is sort of a pot-smoking Isabel Archer, inheritance and all. Cayce is Isabel, with a search engine.” (review, NY TImes, 19 Jan. 2003)

Blogger Thomas M. Wagner praises “Gibson’s uncanny knack for having his finger on the pulse of technology (the first clue to tracing the footage comes in the form of digital watermarking) and überhip pop culture. Hell, Gibson references both Beat Takeshi and Ryuichi Sakamoto in an off-the-cuff manner that indicates he expects you to know who they are. That scores coolness points in my book with a big red pen. Plus, all the characters use Macs!” (SF Reviews. net, 2003)

Pattern Recognition introduces another idea, steganography, as Cayce tries to find the creator of The Footage. “Steganography is about concealing information by spreading it through other information.” (p. 78) An example would be product placement in a Hollywood film. The opposite of this is apophenia, a paranoid condition in which one sees messages hidden in places of random or meaningless data, places where no messages were ever intended. An example would be hearing your father’s voice in the whir of a refrigerator or hearing Satanic messages in a Beatles record played backwards. In the novel Pattern Recognition, Hubertus hires attractive young women to go to bars frequented by fashionable people and to strike up flirtatious conversations. In the course of these conversations, the young women mention a new product or service promoted by the Blue Ant agency as the hottest new trend. The subtext is: ‘If you’re in the know about this product, you’ll impress others, so pass it on.’

The problem with this widespread use of viral advertising–a use that spills out of conventional media into everyday life–is that it begins to colour and tarnish messages of every kind. As Cayce puts it in the novel: “I’m starting to mistrust the most casual exchanges.” (p. 86) Reviewer Toby Litt comments: “In the end, William Gibson’s novels are all about sadness – a very distinctive and particular sadness: the melancholy of technology.” (The Guardian, 26 April 2003) On the other hand, the viral element in the novel, The Footage, spawns an alternate virtual community. Cayce refers to this community as: “a way now, approximately, of being at home. The forum has become one of the most consistent places in her life, like a familiar café that exists somehow out of geography and beyond time zones.” (p. 5) The Footage helps her escape the pain of her own reality into the promise of another reality. “She wonders really if she uses it any other way. It is the gift of ‘OT,’ Off Topic. Anything other than the Footage is Off Topic. The world, really. News. Off Topic.” (p. 48) Cayce later muses how “the mystery of the footage itself often feels closer to the core of her life than Bigend, Blue Ant, Dorotea, even her career. She doesn’t understand that, but knows it … It is something about the footage. The feel of it. The mystery. You can’t explain it to someone who isn’t there. They’ll just look at you. But it matters, matters in some unique way.” (p. 78) The footage has become a religion for Cayce. This returns me to Carl Freedman’s words on Philip K. Dick’s use of advertising, how it hovers between paranoid conspiracy and a “paradigmatic commodity identified with theological mystery.” Abuse, manipulation, delusion, imagination, creativity, hope.

Advertising in these two futuristic novels, The Space Merchants and Pattern Recognition, alternates as an oppressive controlling of others and as part of a quasi-religious quest for spiritual healing, the founding of a new community of like-minded believers. Ads, propaganda and branding are essential elements of modern communications. New technology needs to be promoted. It also enhances, speeds up and revolutionizes communication. The ad man of the 1950s is brash, confident, ultra-competitive. As an insider in the ad business, he feels he not only has an edge over others, but also that he has the power to shape his own destiny, using the tools of his trade. The ad woman of the first decade of the 20th century is a cool hunter who is deeply insecure, ambivalent about the morality of her job, uncertain of her exact role or the consequences of her actions. In addition to this, she senses that information of any kind is deeply uncontrollable, especially as it spawns virtual worlds. But these virtual worlds may be the most necessary of all, as they offer alternatives to present problems and bring together communities where people use technology in creative ways to suit their unique needs and define the avenues they want to explore.