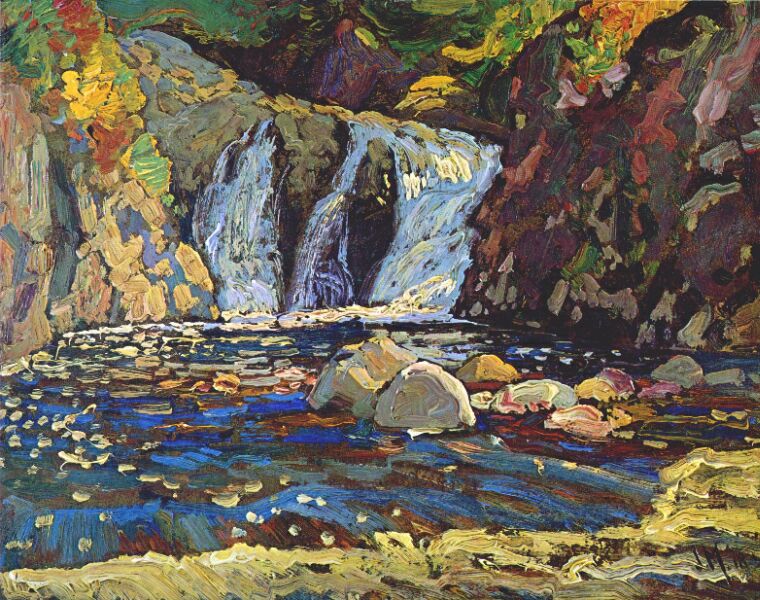

With their romantic vision of the Canadian landscape, the Group of Seven portrayed nature as strong, resilient and wild. They equated the land, its dense growth of trees through the changes of seasons, and vast waterways, with the youthful nation: a site of promise and possibility.

But the group were very much artists of their time, involved in the currents and paradoxes of their time. For instance, they were city-based artists who painted landscapes devoid of people. Much of their training and income derived from commercial assignments. These image-makers of wild spaces started their careers in a small office in Toronto, creating ads selling such things as women’s underwear, hair products and army recruitment posters. Is it high art or commercial art that best reflects the changes happening around us? The answer, of course, is both. And the Group of Seven were deeply involved in both.

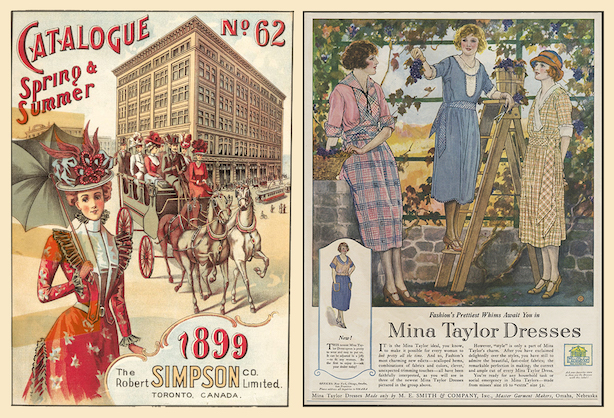

The above ads demonstrate how fashion moved away from turn-of-the-century corsets and bustle skirts to the loose-fitting dresses and hatless bob-haired styles of the flapper era. In a short span of twenty years, a world war raged and women gained the right to vote. A revolution of prosperity, driven by machines, international trade and urban life was well underway. Modern art, with its love of innovation, reflected this global transformation.

Just how modern were the Group of Seven artists? Most of the artists are best described as restless, moving about from job to job, often travelling and painting on the fly. Some members of the group had studied art in Europe, some fought in the war or were involved in war-time messaging. Through their day jobs in advertising, members of the group were steeped in post impressionism, art nouveau and other modernist trends. Working on weekends in rented cottages, taking countless train rides from Toronto to Algonquin Park and beyond, their working methods forced them to paint with speed and spontaneity. As travel artists, they fancied themselves pioneers of a new path, throwing off centuries of dull tradition in favour of a more daring and personal vision. This is the very spirit of modernism.

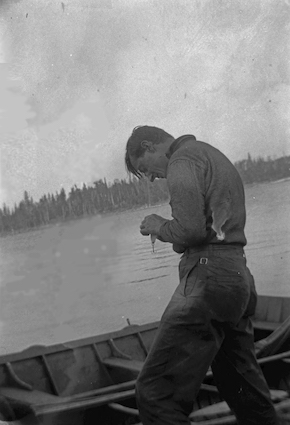

Tom Thomson (1877-1917) was born just 10 years after Confederation. He was influenced by a great nation-building project. The expansion of industry and spread of the railway allowed him and his fellow artists access to remote areas. Thomson was an anomaly in almost every way. He was 27 years old when he first picked up a paintbrush, 39 years old when he died. One of the most likeable members of the group, his life ended in a wholly unexpected quarrel with an unstable man who he thought was his friend.

This leads us to the first paradox of the Group of Seven: Tom Thomson was a Pacifist who refused to participate in the horrors of World War 1. Instead he retreated to the safety and isolation of a provincial park in northern Ontario, where he was promptly murdered. In true Canadian fashion, this loss is too cruel for us, so we call Thomson’s death a mystery. Before the Group of Seven had officially formed, which wouldn’t happen until 1920, they had lost their most gifted member. Thomson’s long shadow follows the group as they search for artistic identity.

The group’s journey intersects with another important trend: the national parks movement. It starts in the United States and Canada follows suit. From the start, Canadians are conflicted over the purpose of their national parks. Are these protected spaces meant for recreation, conservation, or the development of industry? Some members of the Group of Seven were avid campers and woodsmen, others not so much. But in their art, they come together in a shared vision of the country, using daring colours (no more dull green and brown landscapes for them!) and thick dabs of paint that give the images a fresh and vibrant look.

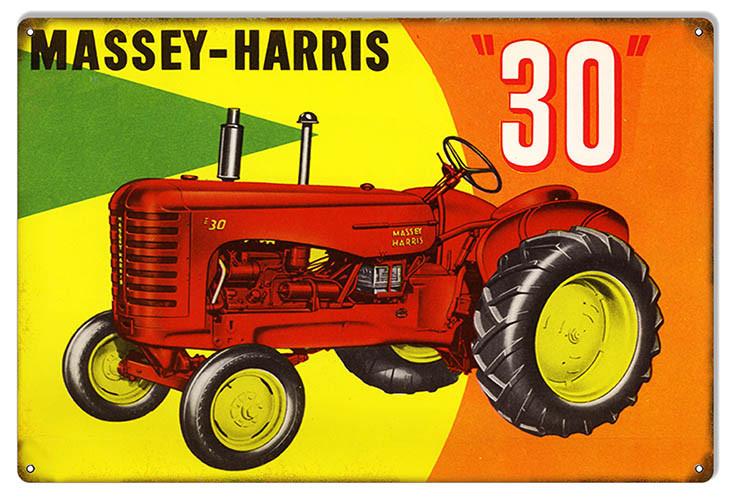

The Group of Seven was assisted financially by the most energetic member of the group, Lawren Harris and his friend, Dr. James MacCallum. These two constructed a building in Toronto, which they divided into studios and rented out to their artist friends at an affordable rate. Tom Thomson lived rent-free in a small cottage in the back. Harris and MacCallum also arranged for exhibitions and trips to northern Ontario. Harris’s wealth came from the Massey Harris company, which sold modern tractors to farmers around the world.

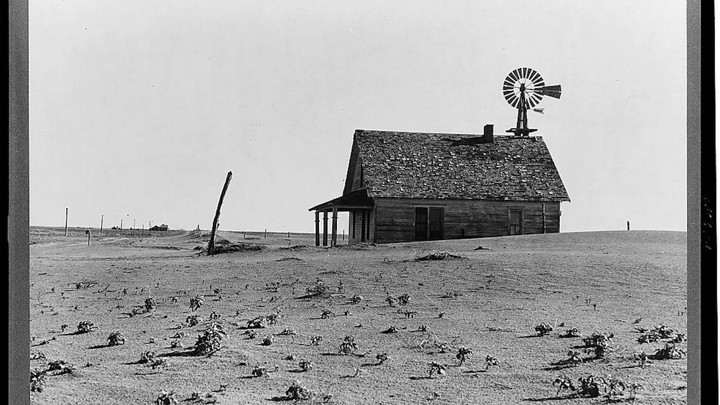

In the second paradox of the Group of Seven, the Massey Harris farm equipment revolutionized agriculture, bringing with it all the rewards of mechanized, big-scale industry, but at an unexpected cost. No one was aware of it at the time, but one of the consequences of industrial agriculture, with its deep plowing and soil disruption, is erosion and the inability of land to hold water. In times of drought, uncovered soil turns to dust and blows off in huge destructive clouds, leaving great tracts of land in a state of ruin. This is what happened during the Dustbowl of the 1930s. These drought-ridden farms are one of the indelible symbols of the Great Depression.

The glorious images of wilderness abundance that the Group of Seven specialized in were no longer relevant for a time of deprivation and environmental disaster. It is no coincidence that this is exactly the moment, the 1930s, when the Group disbanded.

A few of the artists became teachers and continued to exert influence on a younger generation. But with the arrival of the Second World War, their time had passed and new styles took over. However, in our national museums, the Group of Seven has gained status equivalent to a gold standard. They were, after all, Canada’s first homegrown art movement and remain among our best known and most popular artists with public and collectors.