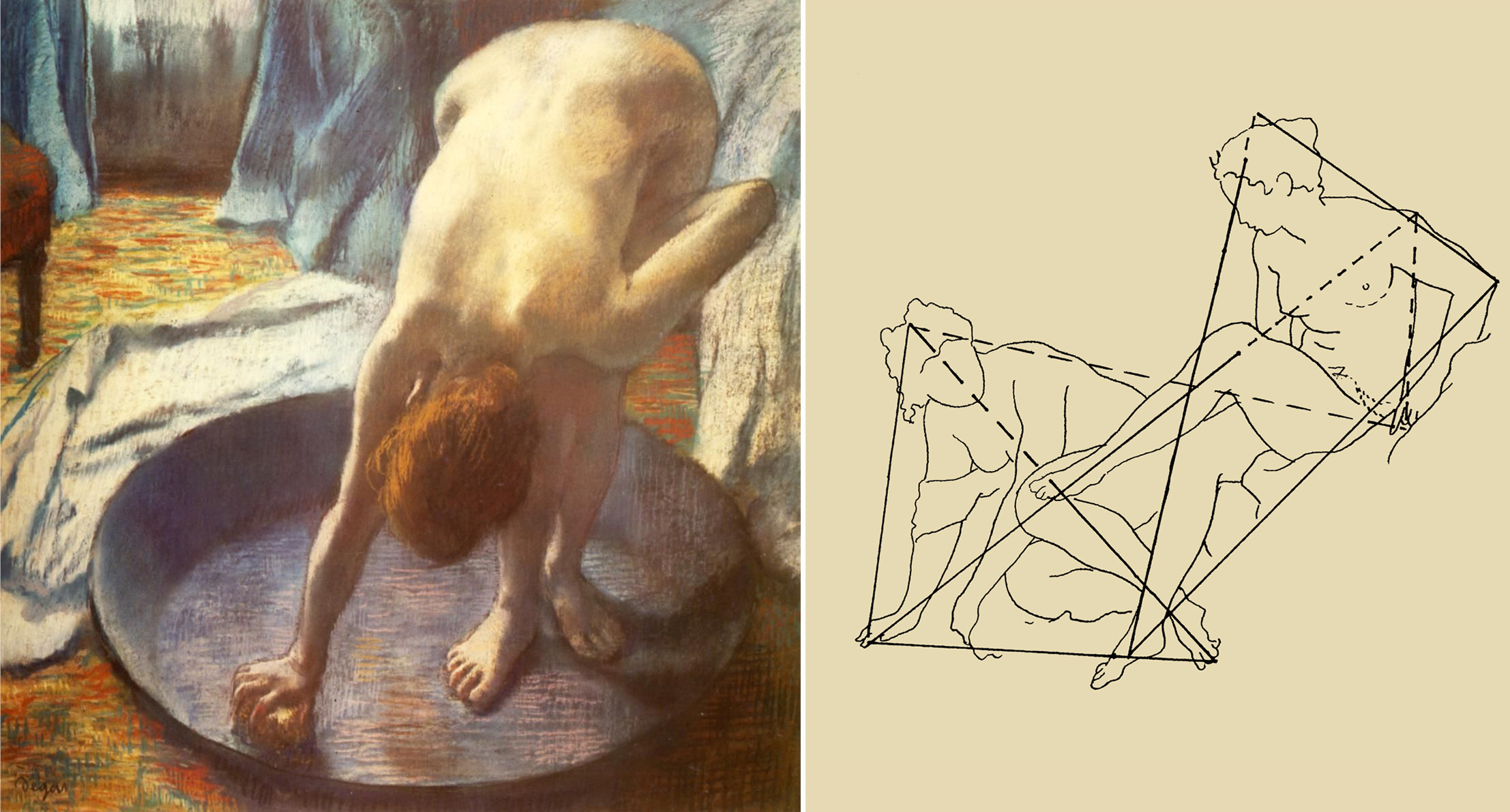

This week’s subject is bathtubs and baths and how artists treat and transform them. In the top right sketch, a study by Giovanni Civardi after François Boucher, we see two bathing goddesses looking ever so elegant even without clothes. Every limb tilts to form a triangle; the overlapping shapes create a fascinating rhythm. Top left, Degas captures a working-class woman bending awkwardly in a shallow basin. It’s an everyday ritual, the raw minutiae of life poured through the finest aesthetic filter.

In the novel, Ulysses by James Joyce, a middle-aged ad salesman daydreams about taking a bath in the middle of the day. These are his thoughts: “Enjoy a bath now: clean trough of water, cool enamel, the gentle tepid stream. This is my body.” The man sees the world in physical terms; he’s comfortable with his body, which he imagines in water: “He foresaw his pale body reclined in it at full, naked, in a womb of warmth, oiled by scented melting soap, softly laved. He saw his trunk and limbs riprippled over and sustained, buoyed lightly upward, lemonyellow: his navel, bud of flesh: and saw the dark tangled curls of his bush floating, floating hair of the stream around the limp father of thousands, a languid floating flower.” The character’s name is Leopold Bloom and, in this passage, he compares his penis to a floating flower.

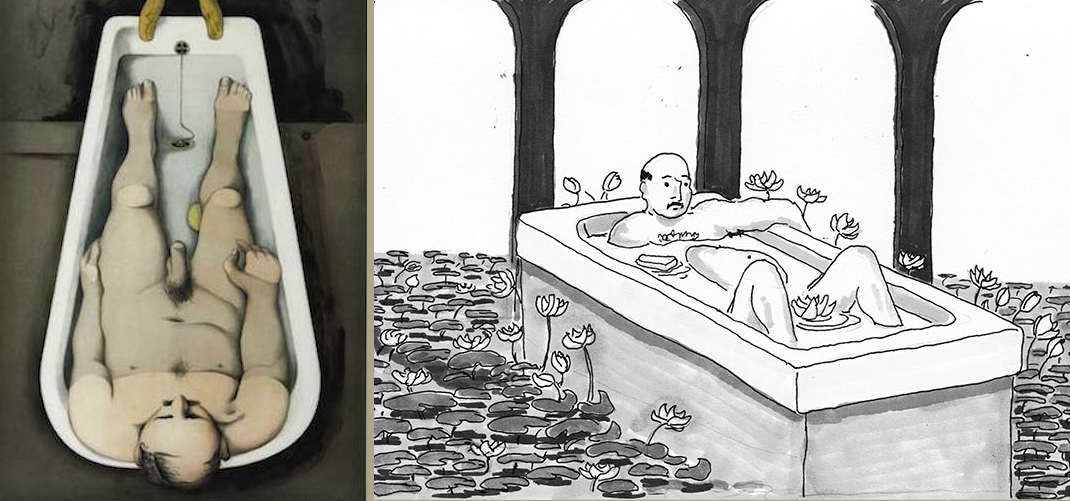

Two artists picture Leopold Bloom in the bath. Right, looking down by Richard Hamilton. Left, cartoon of a tub in a lily pond by Robert E. Lee

The illustrations above show two artist’s rendition of this text. On the left, British Pop artist Richard Hamilton, most famous for designing the cover of The White Album by the Beatles, plays it surprisingly straight. It strikes me how Bloom, everyman hero of Ulysses, with his get-rich-quick schemes, curious mind, attraction to advertising and things of the moment, makes a fitting subject for Pop Art. Here is Hamilton’s definition in 1957 (five years before Andy Warhol’s soup cans): “Pop Art is popular, transient, expendable, low-cost, mass-produced, young, witty, sexy, gimmicky, glamorous and Big Business.” In Robert E. Lee’s delightful cartoon, right, the flowers in and around Bloom’s tub are waterlilies, with one strategically placed between the bathing man’s legs. The flower that hides private parts recalls the well-placed fig leaf in Renaissance paintings.

Two Baptisms: Piero della Francesca, Baptism of Christ, 1448, and The Bible, miniseries, 2013. Produced by Roma Downey and Mark Burnett. John the Baptist (Daniel Percival) lowers Jesus (Diogo Morgaldo) in the waters of the River Jordan.

During the Renaissance, the bathing theme merged with Christian subject matter. In images depicting the Baptism of Christ, water takes on transformative properties. The baptism represents a new beginning, spiritual life. I like how, in this modern Biblical epic, the witnesses are in the water, in the thick of the action. An interesting aside, The Bible miniseries was produced by Mark Burnett. Burnett is one of the inventors of Reality TV with hit shows The Survivor, 2000, The Apprentice, 2004 (featuring Donald Trump) and Shark Tank, 2009.

Bathing can have a spiritual or otherworldly aspect. Mythological scenes often represent bathing nymphs or goddesses and their attendants–a pretext for painting beautiful naked bodies. In Puvis de Chavannes’ dream-like image, the scene recalls a golden age in the distant past, when harmony with nature was the norm. Puvis was much admired by the surrealists of the 1920s.

In contrast, George Seurat painted bathers not as idealized ethereal types but as contemporary working-class people getting away from the inner city of Paris (note the belching smokestacks in the distance) for a moment’s leisure in outlying parks. There are faint hints here of Seurat’s later experiments with light and colour.

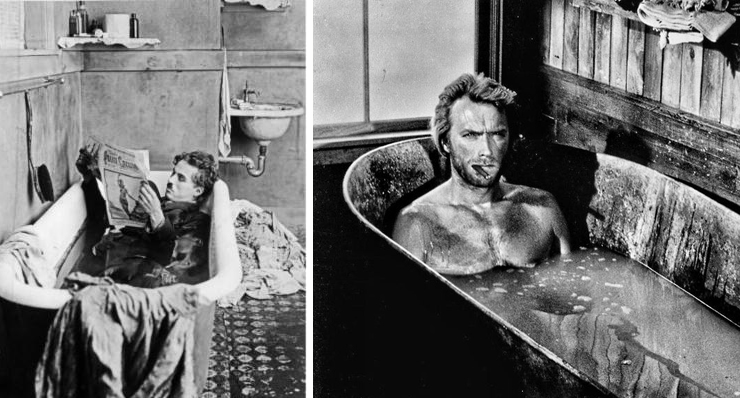

Baths can have a civilizing effect. In many cowboy movies, there’s a scene where a dusty traveller comes in from the frontier and must acclimatize to town life, which starts with a bath and a shave. Iconic film stars Charlie Chaplin (Pay Day, 1922) and Clint Eastwood (High Plains Drifter, 1973), have their moments in the suds. I sense this tramp and cowboy are irredeemable, free spirits to the core–no scrubbing off their inner wild. Baths are sublime but open to kidding. See Jessi Klein’s humorous polemic on the over-ratedness of baths. (The New Yorker, May 2016)

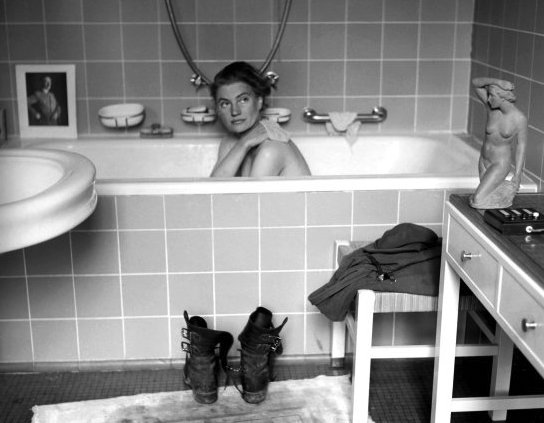

The photographer and collaborator with Paris surrealists, Lee Miller, travelled with the American troops who fought their way into Germany toward the end of World War II. Here Miller saucily and sardonically photographs herself in Hitler’s private bath. She frames herself between a photograph of Hitler and a classical nude statue. Miller’s discarded army boots suggest the wartime setting and give a hint that she has worked hard for this moment–it’s the revolution of ordinary citizens invading the palace.

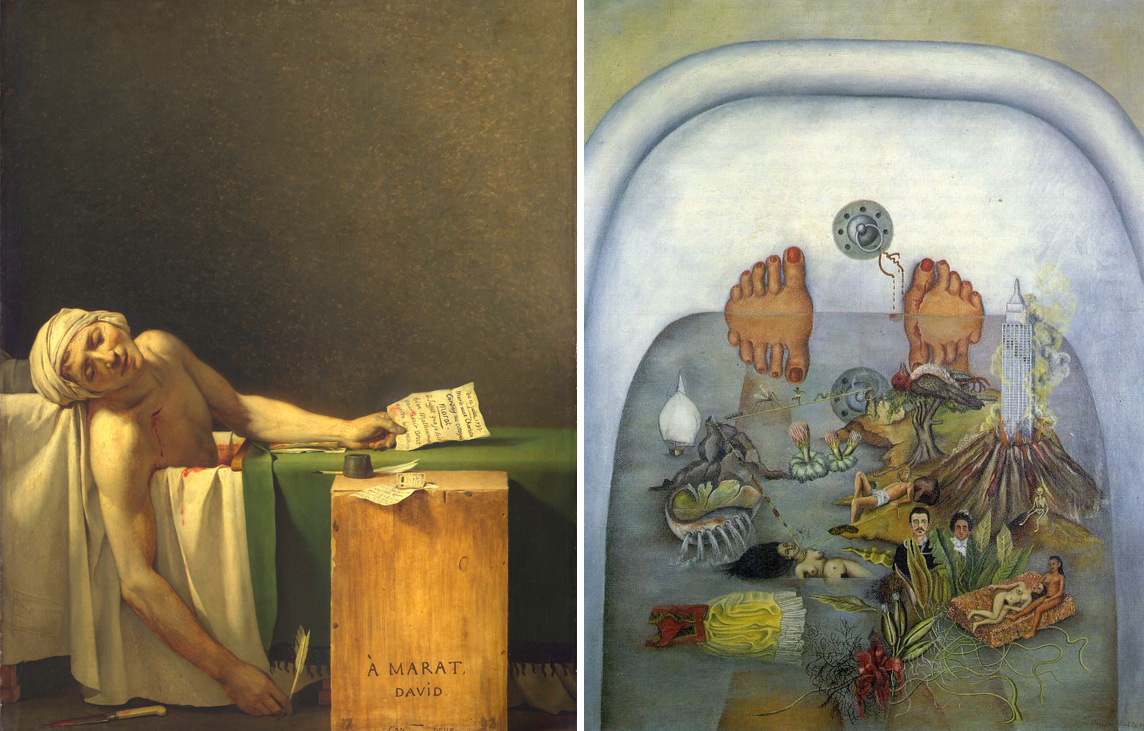

Speaking of revolutions, in 1793, French artist Jacques-Louis David painted a touching tribute to slain revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat. Marat was murdered in his bath, where he worked most days because of his debilitating skin disease. This was a real life tragedy. In Alfred Hitchcock’s fictional film, Psycho (1960), a woman on the run is killed in a motel shower. Both painting and film feature violations of private moments when people are unsuspecting and vulnerable. The artist David, who had a skill for surviving violent political upheavals (he was simply too useful a propagandist for tyrants to kill) would go on to paint stirring portraits of the great anti-revolutionary leader Napoleon.

Frida Kahlo imagines her bath water harbouring private and collective memories. For most of her adult life, Kahlo suffered terribly from leg and lower body injuries incurred in a bus accident when she was 18-years-old. Her pain and sense of isolation is represented by the bleeding right foot. The skyscraper emerging from a volcano, besides the obvious sexual connotations, captures the duality of living briefly in New York but coming from Mexico where land and nature captured her imagination. Kahlo makes reference to her dual European and Mexican ancestry, heterosexual and lesbian encounters, and traditional and modern ways. The waters suggests the unconscious material from which artists like Frida draw their inspiration.

Gods and nymphs, salesmen, tramps and cowboys, surrealist photographers, revolutionaries, wounded artists and daydreamers–what do they all have in common? They all take baths, make fun of baths, use baths for seduction, paint baths, glorify baths, daydream of baths or die in them. Warm waters stir human imagination even in small-sized tubs.