-

Tom Ripley is a counterfeiter, con artist and murderous anti-hero, yet his journey of self-discovery is strangely compelling in Patricia Highsmith’s gripping crime novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley, first published in 1955. There are many ways to regard this novel: as a portrait of human pathology, as an adventure story, as a travelogue, as a critique of American values of the 1950s. Today I approach this novel as part of a series of blogs on water imagery and symbolism in art & literature.

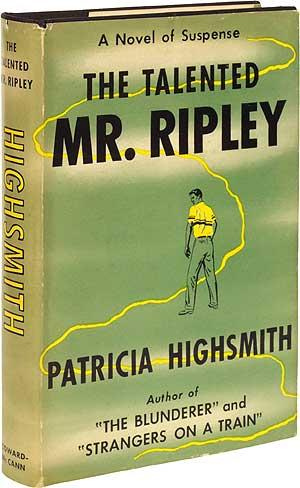

The cover of the first edition gives some hint to the meaning of water in the novel. It serves as a barrier separating characters, preventing their understanding of one another. Water also runs a meandering, unpredictable course–like the twisting plot that features false identities, murder, pursuit and cover-up.

Early in the novel, Highsmith upsets expectations of water signifying anything romantic. “The atmosphere of the city became stranger as the days went on … As if when his boat left the pier on Saturday, the whole city of New York would collapse with a poof like a lot of cardboard on a stage. Or maybe he was afraid. He hated water. He had never been anywhere before on water, except to New Orleans from New York and back to New York again, but then he had been working on a banana boat mostly below deck, and he had hardly realized he was on water. The few times he had been on deck the sight of the water had at first frightened him, then made him feel sick, and he had always run below deck again, where, contrary to what people said, he had felt better. His parents had drowned in Boston harbour, and Tom had always thought that had something to do with it, because as long as he could remember he had always been afraid of water, and he had never learned how to swim.” (p. 25)

The Queen Mary steaming down the Hudson River in 1946. Tom would have boarded a similar ship on his passage to Europe. Photo by Andreas Feininger

The author connects water in Tom’s mind with childhood trauma. But the ocean voyage also has a liberating effect on Tom. “He began to play a role on the ship, that of a serious young man with a serious job ahead of him … He was starting a new life. Goodbye to all the second-rate people he had hung around and had let hang around him in the past three years in New York. He felt as he imagined immigrants felt when they left everything behind them in some foreign country, left their friends and their relations and their past mistakes, and sailed for America. A clean slate!” (p. 34-35)

The story reflects aspects of Highsmith’s own life. Her self-exile from the USA, restless travels, learning languages, making new friends and growth as a writer. The excitement of fresh encounters is tempered by memories of an unhappy childhood and the persecution she felt living as an openly gay woman in McCarthy-era America. She spent time in Mexico, Italy, and France before settling in Switzerland and finding a receptive ear at the Swiss publishing house Diogenes Verlag.

In Highsmith’s novel, the first function of water is to separate the characters into two realms: the worldly but rootless Europeanized Americans and the vulgar money-making stay-at-home Americans. The next function of water is to set Tom on his way to discovering what kind of person he is, identifying and developing his own unique talents. This is the classic hero’s journey, something the reader might well identify with. Perversely Tom’s talents involve lying, deception and murder–all socially unacceptable traits. Tom tries to fit in with the people he encounters, and is stung by their rejection of him. The rejection is largely based on class prejudice. Tom is not rich and independent like the others. He does not own a yacht. He lacks their education and knowledge of art and foreign languages. However he is a quick study and is able to mimic their ways quite easily. At first this mimicry amuses the superficial young aristocrats, who nonetheless feel themselves to be innately superior to Tom. This smug superiority arouses a murderous resentment.

The novel changes moods abruptly. These changes often occur around water. The first murder takes place on water. Tom Ripley kills a man, but has trouble disposing of the body. In the process Tom is accidently knocked overboard. “He was in the water. He gasped, contracting his body in an upward leap, grabbing at the boat. He missed. The boat had gone into a spin. Tom leapt again, then sank lower, so low the water closed over his head again with a deadly fatal slowness, yet too fast for him to get a breath, and he inhaled a noseful of water just as his eyes sank below the surface. The boat was farther away. He had seen such spins before: they never stopped until somebody climbed in and stopped the motor, and now in the deadly emptiness of the water he suffered in advance the sensations of dying, sank threshing below the surface again, and the crazy motor faded as the water thugged into his ears, blotting out all sound except the frantic sounds that he made inside himself, breathing, struggling, the desperate pounding of his blood.” (106-107)

This terrible scene is followed by a couple of pages detailing Tom’s escape from death and his recuperation in a nearby town. He boards a train and feels himself begin to change. “The white, taut sheets of his berth on the train seemed the most wonderful luxury he had ever known. He caressed them with his hands before he turned the light out. And the clean, blue-grey blankets, the spanking efficiency of the little black net over his head–Tom had an ecstatic moment when he thought of all the pleasure that lay before him now … other beds, tables, seas, ships, suitcases, shirts, years of freedom, years of pleasure. Then he turned the light out and put his head down and almost at once fell asleep, happy, content, and utterly, utterly confident, as he had never been before in his life.” (p. 111-112)

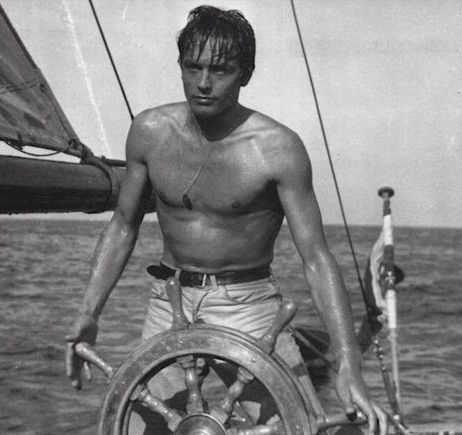

Actor Alain Delon plays Tom Ripley in the French film, Plein Soleil, 1960 (directed by René Clément), the first of many adaptations of The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Water suggests a reversal of fortunes. From grovelling subservience to wealthy independence. A powerless working-class youth, unrecognized by the world, becomes a resourceful self-confident criminal. But Tom’s confidence periodically gives way to paranoia. Just as water covers up evidence of Tom’s crime, the fear arises that either the body or the stolen boat will wash ashore or resurface in some incriminating way. It is part of Highsmith’s perverse genius that she encourages the viewer to root for the villain, to cheer when he eludes capture, keeping this addictive story going.

The novel ends as it begins on a passenger ship. The sea as barrier and divider of people, as deadly, deceptive, ever-changing in its moods, is an appropriate symbol for this reckless adventurer who counts on luck and his own devious improvisational skills to make his way in the world.