I grew up surrounded by self-help books. My father’s library was heavily weighted with manuals on how to exercise, how to pray, how to run a business, how to get rich, how to be a philanthropist. I thought the whole advice thing was a bit overblown and desperate, (even as I started adding titles to my own library like Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces and Michael Pollen’s Food Rules), but then self-help is a booming billion dollar business so—how to explain? Why are so many people hooked on self-help?

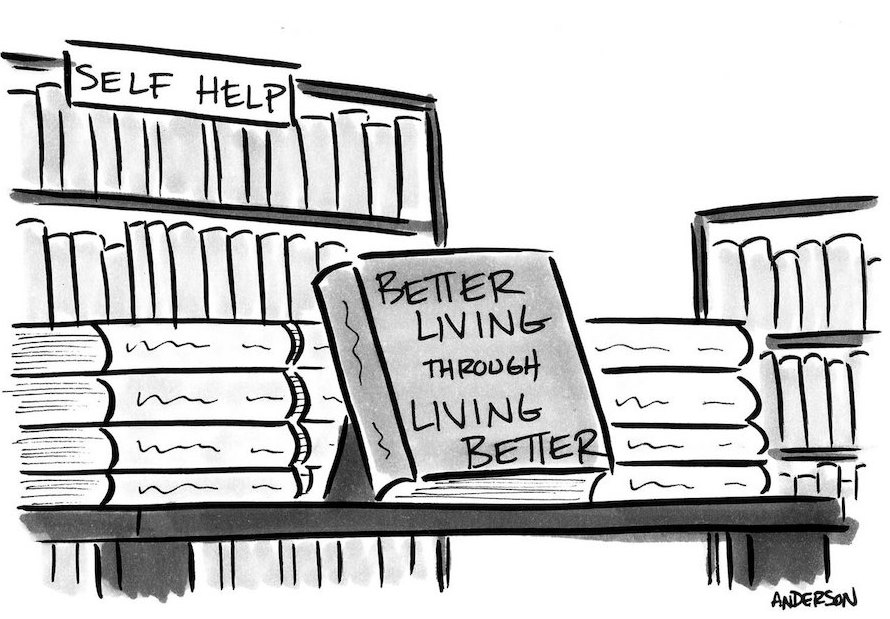

On the one hand, the books are full of extravagant promises; on the other hand, they’re clichéd and use examples that seem miles away from anyone’s life. The titles are incredible: Life and Death in One Breath, The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up, Atomic Habits, Make Your Bed, The 4-Hour Workweek, 12 Rules for Life, The Five Love Languages, and The Happiness Project. Self-help is often related to such things as the Human Potential Movement and the Law of Attraction (defined by Marshall Sinclair as “the belief that positive or negative thoughts bring positive or negative experiences.”) Guaranteed best-sellers pour out from television gurus Tony Robbins (Awaken the Giant Within) and Oprah Winfrey (What I Know For Sure and The Path Made Clear). Who wouldn’t want their path made clear? Who doesn’t want to be a giant? No, maybe not a giiant–you’d have to buy new furniture. There’s even an anti-self-help self-help genre. Life seemed simpler when Samuel Smiles wrote in the 19th century: “Heaven helps those who help themselves.”

Harvard English professor Beth Blum summarizes the usual explanations: “Economists stress how late-19th-century class mobility created new anxieties over self-presentation among the aspirational middle classes. Sociologists and scholars of religion outline the way the anomie of industrial modernity—urbanization, secularization, the division of labor—created a vacuum that self-help strove to fill. Historians discuss these and others factors as part of “the turmoil of the turn of the century,” which led to the rise of the “therapeutic ethos.” (The Self-Help Compulsion, 2020) In a nutshell, we need therapy for our empty, aspirational anxieties …

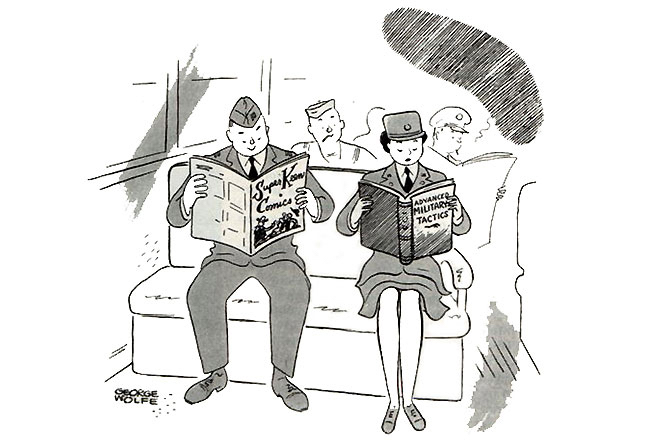

In a 2019 lecture Mark Jackson, professor of the history of medicine, University of Exeter, links self-help ambitions to benchmark moments in history, such as the First World War and the Great Depression. Here’s a war-time example: Matilda Parsons, a teacher and widow of an army officer, declared in a newspaper interview in 1917: “It is a paradox of life that we do not begin to live until we begin to die. Death begins at 30, that is, deterioration of the muscle cells sets in. Most old age is premature, and attention to diet and exercise would enable men and women to live a great deal longer than they do today. The best part of a woman’s life begins at 40.”

A social reformer, Parsons was dismayed by middle-aged women who had “let themselves go.” She argued that women needed to be strong and fit, and should educate themselves in order to contribute fully to the shaping of the nation. The immediate concern was to take over jobs and the management of factories while men were away at war. In her interview, Parsons unwittingly created a meme and like many memes, it began to take on a life of its own. Though her phrase “the best part of a women’s life begins at 40” was abbreviated to the catchier, more universal “life begins at 40.”

During the Great Depression, American journalist Walter Pitkin published a self-help book called Life Begins at 40 in 1932—the Will Rogers film version appeared in 1935. The author’s goal was to combine self-renewal with recovery from a collapsed economy. Pitkin advised older workers to retire early to create job openings for younger men. He also advised retirees to spend their money freely “pursuing self-fulfillment through material improvement, leisure and the art of living.” During a period of doom and gloom, Pitkin sensed that populations as a whole might recover, if people just spent a little money to make themselves feel better about themselves.

It’s no coincidence that the American Dream was conceived at about this time. In The Epic of America, 1931, James Tuslow Adams lays out the American promise of social order, democratic values, and prosperity for all. This dream is severely tested by the Second World War. Thereafter it becomes “a dream of material plenty, motor cars and high wages.” According to Edmund Burgler, author of The Revolt of the Middle-aged Man, 1958, the top priority of the post-war generation is the pursuit of “happiness in a hurry.”

Burgler describes the mindset of the middle-aged person who has not lived up to expectations: “I want happiness, love, approval, admiration, sex, youth. All this is denied me in this stale marriage to an elderly, sickly, complaining, nagging wife. Let’s get rid of her, start life all over again with another woman. Sure, I’ll provide for my first wife and my children; sure, I’m sorry that the first marriage didn’t work out. But self-defense comes first, I just have to save myself.”

Seduced by a dream of collective improvement that was no longer achievable, the post-war generation resort to a reflex of selfishness and greed. This new direction is aided and abetted by mass media, advertising and consumer culture.

In the above cartoon by Patrick Chappatte, a man sits at a kitchen table with a bleak look on his face, his body language conveys a sense of solitude and spiritual terror as he asks, “What is the meaning of my life?” In the next room, comfortably surrounded by magazines, TV and picture window, his wife or daughter answers, “Ask Google.”

Technology is almost certainly not the answer. People seek direction, solace and hope. Meaningful action. According to Beth Blum, one source that historically addressed this need was literature–or the stories that underpin our culture, our collective consciousness. In the past, literature drew heavily upon myths and moral tales with their moments of enlightenment. These stories often provided clear examples of good and bad behavior and no one questioned the notion of reading for improvement. However in recent years, serious authors feel that advice to the reader has no place in a story concerned primarily with realism and artistic autonomy.

Where literature fears to tread, self-help books rush in (with approximately 150 new self-help titles published every week). As Professor Blum puts it: “At a time when the value of literature is often called into question, self-help offers … promises of transformation, agency, culture, and wisdom that draw readers to books.” So it might be that there’s not too much self-help in our culture, it’s just not active in the places where one might reasonably expect to find it–in the stories of our generation that we need to tell ourselves.