The cave paintings of southern France and Spain present one of the great mysteries of art. Why were these works created? The paintings are mostly of animals: bulls, aurochs, horses and bison. In the Lascaux cave, one of the giant bulls is 17 feet long. The animals, painted with earth-coloured minerals, appear to be in motion; none of them are grazing.

What is the meaning of this prehistoric art? We can only conjecture. The usual explanations touch on magical properties, hunting and religion, or having to do with initiation, ancestry and entertainment. Does any art in the 20th century deal with similar material? And can we learn anything from modern-day examples of herds, cattle and humans?

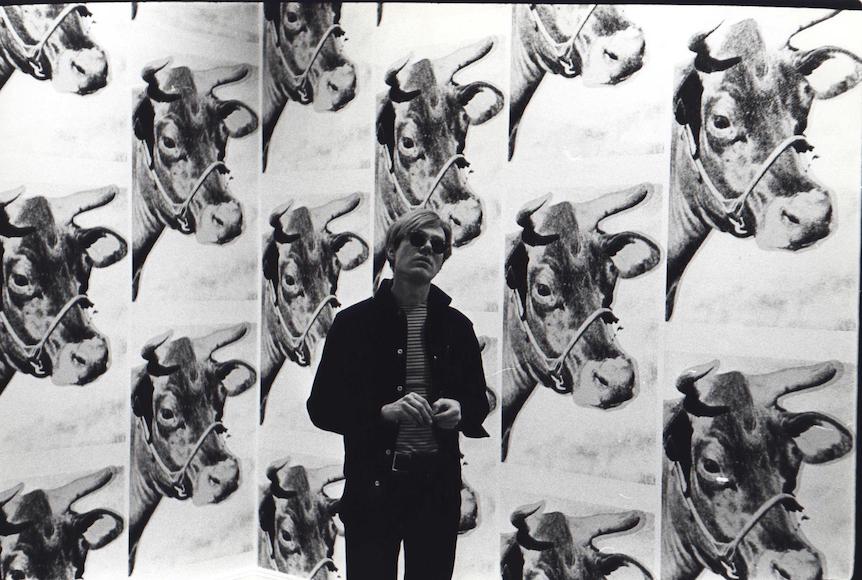

For example, Warhol’s cow wallpaper mocks the way landscape art, often featuring cattle, can become a piece of decoration in a room. The repeating heads of identical cows are absurd, yet powerful–the hypnotizing effect of mass media.

Perhaps the 20th century artist most associated with bulls is Pablo Picasso. “As a Spaniard it was inevitable that the bull, the bullfight, and eventually the Minotaur, would concern Picasso.” So writes Martin Ries in Art Journal (Winter 72/73).

Picasso draws and paints bulls in a variety of contexts. The bull could be a symbol of Spain, Picasso’s birthplace, or a symbol of sacrifice or death. Picasso portrays the minotaur as a monster, a lover, an embodiment of brute strength. At other times, the half bull-half man appears vulnerable, a homeless wanderer or uncomprehending actor in elaborate scenes of war and human suffering.

There is a dream-like quality to the image below that suggests a surrealist paradox: the violent solitary man lives under threat of being civilized. In his personal life, Picasso’s marriage had fallen apart–he couldn’t divorce because he was Catholic–and his mistress had just gotten pregnant.

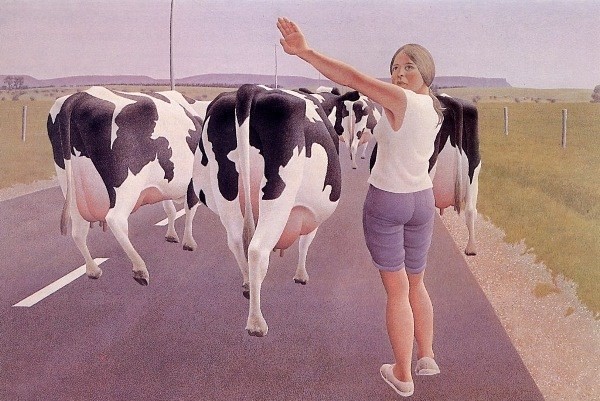

Not bulls but cows. Canadian artist Alex Colville’s magic realist vision, with its pastoral theme, sense of deep space, luminance, and cool confrontation with the viewer, could not be more different from Picasso’s dark dramas. However Colville’s woman and Picasso’s Minotaur make similar gestures with their outstretched arms.

Standing before the Colville painting, the viewer feels like he or she is stopped in a car on a country road. The animals are momentarily in control and there’s not much to do about it. The young woman who makes the gesture is a cross between a modern-day shepherdess and a traffic cop. Perhaps she’s a stand-in for the artist–all artists want viewers to stop before their paintings. Are we being asked to slow down to share the world with the forces of nature we depend so much upon?

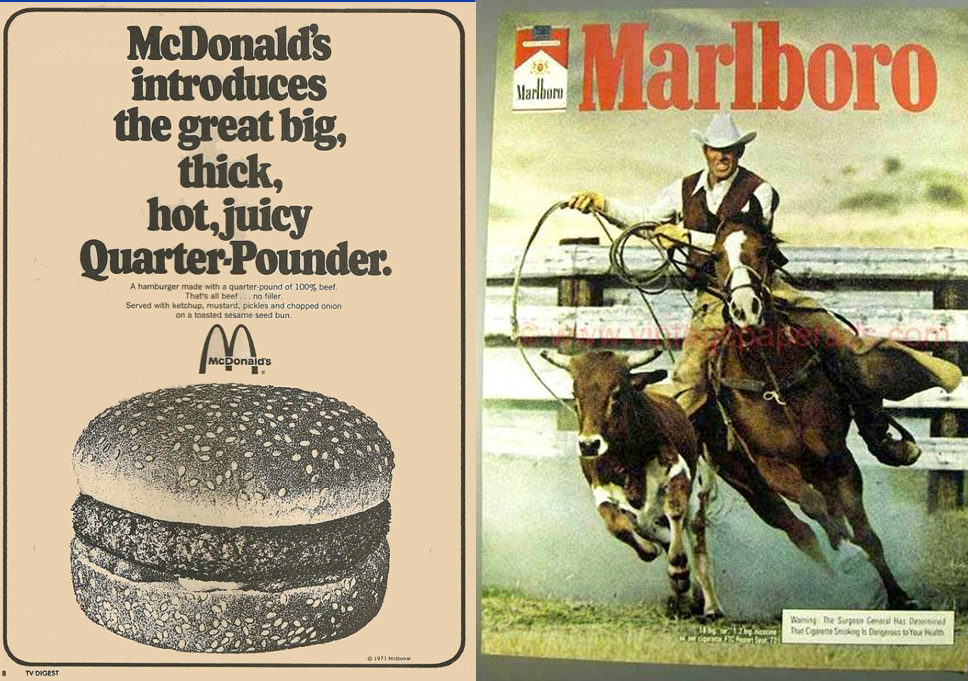

When I look at images, a question I ask is: can we learn more about a time and place from art, from ads or from pop culture? For me, the answer is all three. For instance, the McDonald’s ad above is an artifact of our fast food culture, firmly entrenched by the 1970s. It is not an ad for a restaurant–the information makes no mention of atmosphere or a sophisticated and varied menu. The food is to go and it’s an identical product wherever you buy it. The ad stresses “great” and “big” — (has to compete with whoppers). Its message is the opposite of the Alex Colville painting, Stop for Cows. The last thing a consumer needs to think about at McDonald’s is where did this food come from or were any animals involved.

The Marlborough ad features an action picture of a cowboy about to rope a steer. The image has the iconic appeal of the Old West, portraying a man who’s both free and engaged in work. It suggests a robust way of life, living outdoors, attuned to nature. The man is a skilled horseman and rancher; the young bull has no chance against him. In the unfolding scenario, which we’ve been primed for by a endless stream of related Marlborough ads, we imagine the man will shortly light a cigarette as the camera moves in for a close up of his handsome grinning face.

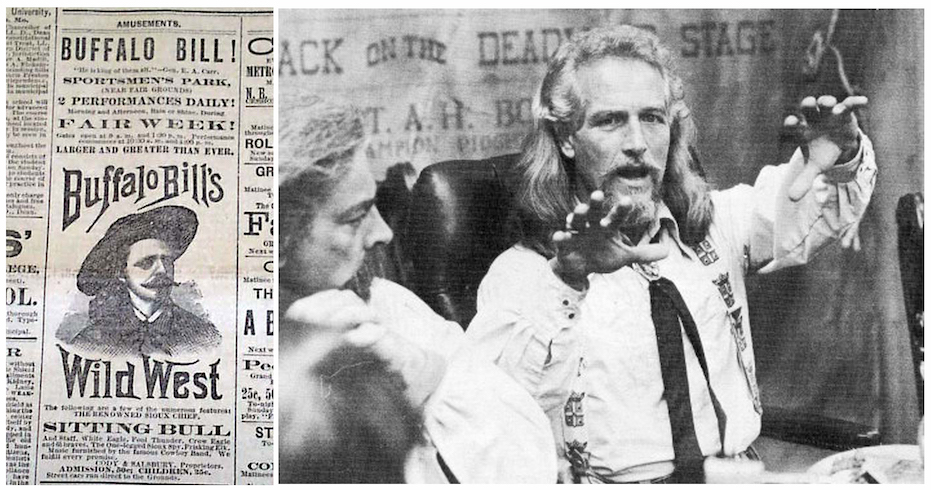

At the same time that Philip Morris Corp was running these cowboy ads, a few irascible filmmakers in Hollywood were causing a stir with their edgy Westerns. No film was more iconoclastic than Robert Altman’s satirical bio-pic, Buffalo Bill and The Indians, 1976.

Reviewers Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat describe the film: “The time is 1885. Colonel William F. Cody (Paul Newman) is the chief attraction in a show called “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: An Absolute Original & Heroic Enterprise of Inimitable Lustre.” Around this vaudeville environment, Buffalo Bill and his entourage have packaged the history of the Wild West in circus stunts and carnival spectacles. When Annie Oakley (Geraldine Chaplin) asks Buffalo Bill why he doesn’t tell the truth in his shows, the superstar replies, “Truth is whatever gets the most applause.”

Throughout the film, Buffalo Bill wears fine clothes and is groomed to the max, but his flowing locks are really a toupee–he’s a manufactured icon who shamelessly turns the story of wild buffalo and native Americans into a show-biz hustle! The implication is that this pattern of false history and self-deception is deeply ingrained in American politics and public life.

Pop culture tends to focus on stories and personalities. Fine artists often go in for a more visceral and shocking impact. The Canadian conceptual artist, Jana Sterbak is best known for her blood red Meat Dress, composed of 50 pounds of raw steaks sewn together in a seductive and revolting garment. The artist called the work a “contrast between vanity and bodily decomposition.” Critic Deborah Irmas commented how “Sterbak likes to arouse discomfort” by using objects to trigger controversy and disgust.

The dress idea was revisited by pop star Lady Gaga, who wore a similar concoction to the MTV Video Music Awards in 2010. “Lady Gaga divides opinion,” Laura Roberts reported the next day for The Telegraph. “The singer collected eight awards while wearing the Franc Fernandez-designed outfit, complete with boots, purse and a hat made from cuts of beef. Cher, who presented the prizes, wrote on her Twitter account that as an “art piece it was astonishing! Everyone’s talking about it!” Lady Gaga later expressed to her friend, talk show host Ellen Degeneres, that sexual politics lay behind her publicity stunt: “I am not a piece of meat!”

The epic book project, Genesis, 2013, took photographer Sebastiao Salgado eight years to complete, as he documented parts of the world–rainforests, deserts, volcanoes, islands, and arctic regions–untainted by modern life. This photo of migrating reindeer in Siberia captures the mass movement of a herd of animals, on a 1,000 km trek to northern grazing grounds each spring. The human presence is so small (in the sled at top) it’s easy to miss at first glance.

In her review for The Observer, (14 Apr, 2013) Laura Cumming writes: “Salgado wants to go back to the beginning, to find a world that has not yet been ruined by mankind so that we may see the Eden that time forgot.” Redemption project and personal voyage of discovery, this Utopian photo-journalism, with its Biblical overtones, confronted present day fears of self-destruction, shame and loss of the natural world.

All of these works present different takes on the natural world, seen through lenses of war and peace, commerce and fashion, propaganda and history.

What do they tell us about the Lascaux cave paintings? Every device I’ve mentioned, from mass hypnosis to tribal identity (brand loyalty) to embracing a mobile “cowboy culture”, applies equally to both modern and prehistoric societies. Early humans relied on wild bulls for food and clothing. And I suspect some of the clothing used for special ceremonies was just as outrageous as the meat dress and may also have tested limits of what is revolting and what makes for a good story around a fire. The stories, no doubt, were always changing and turning into myths.

And finally, prehistoric nomadic societies, like the ones that passed through Lascaux, may have witnessed or caused or feared or heard of a few extinction events (loss of species) that would have deeply rocked their world. Their art, like ours, was a mixed bag of fears and dreams, expressions of tribal solidarity, affirmation of a mobile lifestyle–while dependent on other creatures, proud of their skill as trackers and hunters, fearful that they might be too skilled and overshoot their limits and natural laws.