In the days following David Bowie’s death. I listened to the songs “Life on Mars?” and “The Bewlay Brothers” from the 1971 album Hunky Dory. The lyrics intrigued me.

I was stone and he was wax so he could scream and still relax

Unbelievable … And my brother lays upon the rocks

He could be dead, he could be not, he could be you

He’s chameleon, comedian, Corinthian and caricature

Shooting up pie in the sky

Bewlay brothers

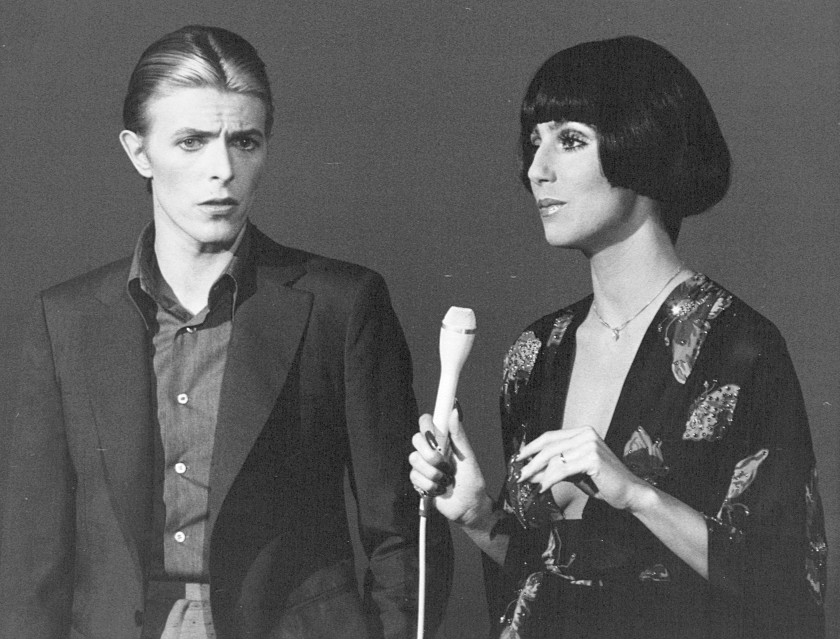

Surely there’s bit of self-portrait in this description. I found a link to a story written by Bowie for the Daily Mail, I went to buy shoes, I came back with Life on Mars, describing 10 favourite underrated songs. Both “Life on Mars?” and “Bewlay Brothers” make the list. About the latter song, Bowie writes:

Surely there’s bit of self-portrait in this description. I found a link to a story written by Bowie for the Daily Mail, I went to buy shoes, I came back with Life on Mars, describing 10 favourite underrated songs. Both “Life on Mars?” and “Bewlay Brothers” make the list. About the latter song, Bowie writes:

“The only pipe I have ever smoked was a cheap Bewlay. It was a common item in the late Sixties and for this song I used Bewlay as a cognomen – in place of my own. This wasn’t just a song about brotherhood so I didn’t want to misrepresent it by using my true name. Having said that, I wouldn’t know how to interpret the lyric of this song other than suggesting that there are layers of ghosts within it. It’s a palimpsest, then.”

I must write Merriam-Webster and suggest they add a new definition for palimpsest: layers of ghosts. The Hunky Dory album has its fair share of ghosts, along with a touch of Nietzsche, aliens, and tributes to other musicians. It’s this mixture of influences, delivered with glitter and angst, that gives Bowie’s work such a unique sense of modernity and other-worldliness.

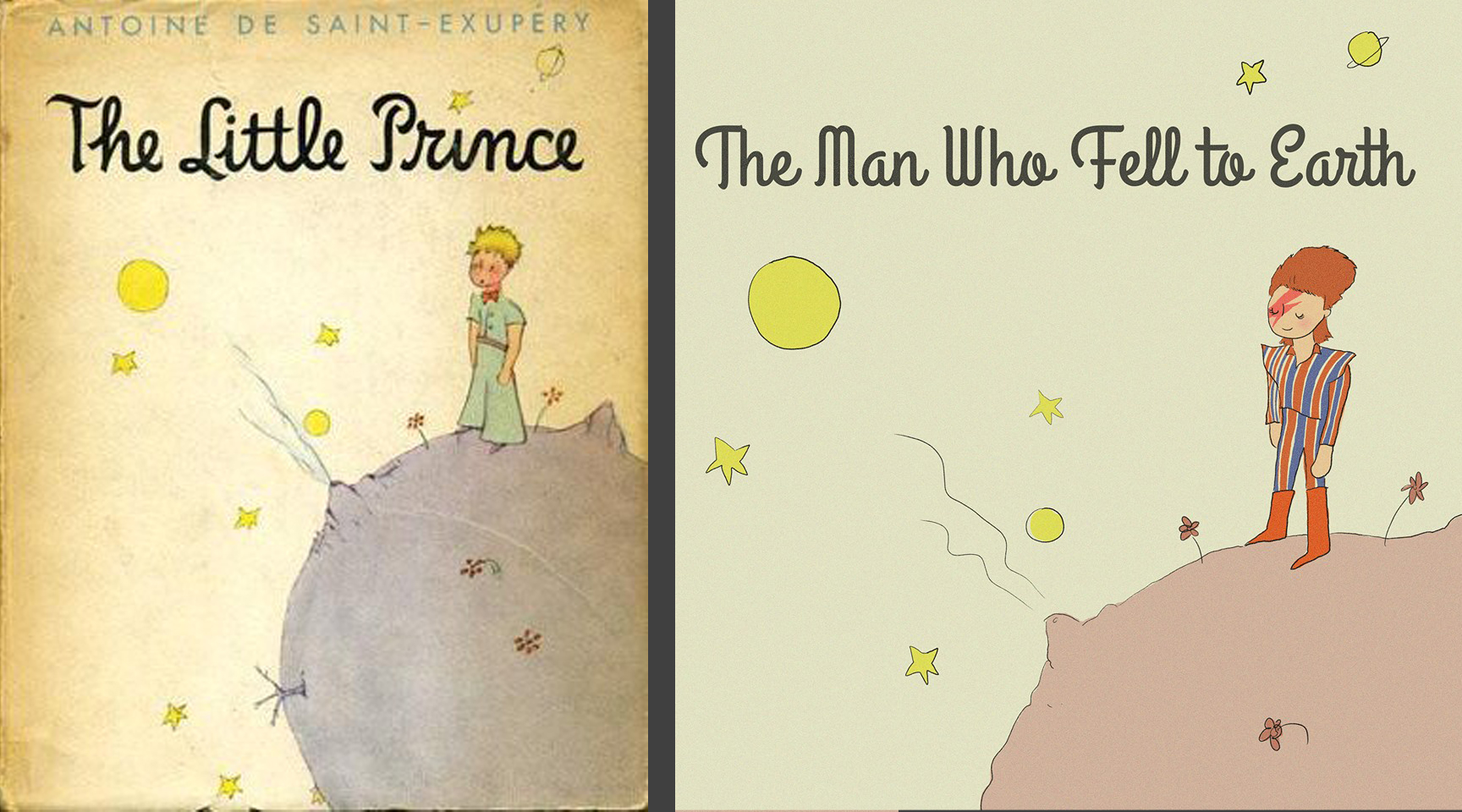

Bowie helps transition us from the 60s world of peace, love and long hair to a Millennial world of sound and vision, mobile devices and remixed songs. Remixed everything. Among the countless Bowie tributes, I found this delightful illustration substituting Bowie for the Little Prince with the caption; “The man who fell to Earth is back amongst the stars. Rest in peace, David Bowie. Illustration/caption by Jarrett J. Krosoczka.”

The musician starts the conversation and fans keep it going. On a recent CBC News story, we’re told that Canadian DJ Skratch Bastid’s remix of Bowie’s song, “Let’s Dance” has become a Facebook meme with over 8 million views in five days.

The musician starts the conversation and fans keep it going. On a recent CBC News story, we’re told that Canadian DJ Skratch Bastid’s remix of Bowie’s song, “Let’s Dance” has become a Facebook meme with over 8 million views in five days.

When I think of mash-ups and Bowie, his cut-up writing method comes to mind. Taking his cue from William Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, Bowie used scissors and pen to spark new thoughts. I ask myself, what would a mash-up of Bowie lyrics look like? Let’s give it a try:

It’s a God-awful small affair

To the girl with the mousy hair (Life on Mars)

He lays her down, he frowns

“Gee my life’s a funny thing, am I

still too young?” (Young Americans)

“You got your mother in a whirl/ She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl.” (Rebel Rebel)

“Are you OK?

You’ve been shot in the head

And I’m holding your brains” (Seven Years in Tibet)

I’m looking for a vehicle, I’m looking for a ride

I’m looking for a party, I’m looking for a side. (Candidate)

He says he’s a beautician and sells you nutrition and keeps all your dead hair for making up underwear. (Jean Genie)

You’ve really made the grade

And the papers want to know whose shirts you wear (Space Oddity)

So I’ll break up my room and yawn and run to the centre of things. (Sweet Thing)

News guy wept when he told us Earth was really dying. (Five Years)

“I’ll make you a deal like any other candidate.” (Candidate)

Seems you’re trying not to lose

Since I’m not supposed to win. (Win)

Oh no love! you’re not alone

You’re watching yourself but you’re too unfair (Rock n roll suicide)

Every chance,

every chance that I take

I take it on the road… (Always Crashing in the Same Car)

I’ve lived all over the world

I’ve left every place. (Be My Wife)

You will be like your dreams tonight. (Joe the Lion)

I’m the space invader. (Moorage Daydream)

Ch-ch-ch-ch-changes

(Turn and face the strange) (Changes)

Then let it be, it’s all I ever wanted

It’s a street with a deal, and a taste

It’s got claws, it’s got me, it’s got you … (Sweet Thing reprise)

Multiple conversations. The search for experience. Exhibitionist finds relief in theatre, masks. The future looks bleak. Experience is filtered through news, media, entertainment. Distrust politicians. Rock ‘n roll is a collective experience. Fame is a trap. Keep dreaming. Space aliens. Nothing is permanent. Embrace change.

My final thought on Bowie: he doesn’t just change for the sake of change. He grows. He develops, he educates himself by traveling, working with gifted people, stretching himself through relationships, marriages, films, families. He stretches himself by renouncing a popular path for an uncertain path. He teaches us all how to become an alien and thrive.

Thanks Bowie, it’s been a blast.