Katsushika Hokusai’s series of travel prints, 36 Views of Mt. Fuji, 1830-32, was so popular, so critically acclaimed, there was demand for a sequel. But not so fast, the younger artist Utagawa Hiroshige published his dazzling series of travel images, 56 Stations of the Tokaido, 1833-34, putting pressure on his rival to do more than just repeat himself.

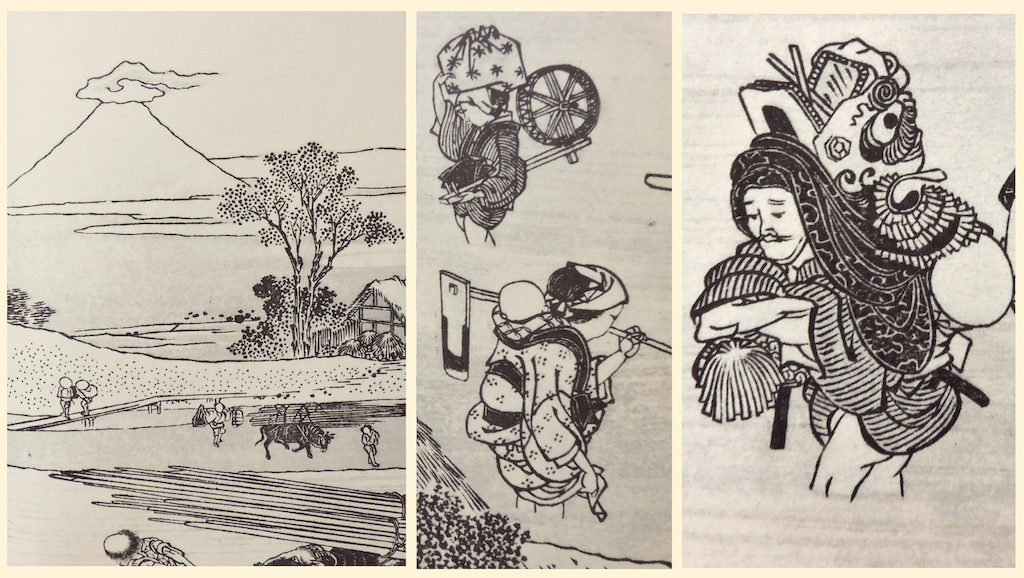

Hokusai responded with his most ambitious project, 100 Views of Mt. Fuji, 1834-35. It was a book of woodblock prints, published in three volumes, using only black and one or two shades of grey ink. Whereas the 36 Views, printed in full colour, represented real places, with recognizable landmarks and features, the 100 Views largely dispensed with place names. These landscapes of the imagination, meticulously rendered, made use of closely observed details gathered over a lifetime of travel and study.

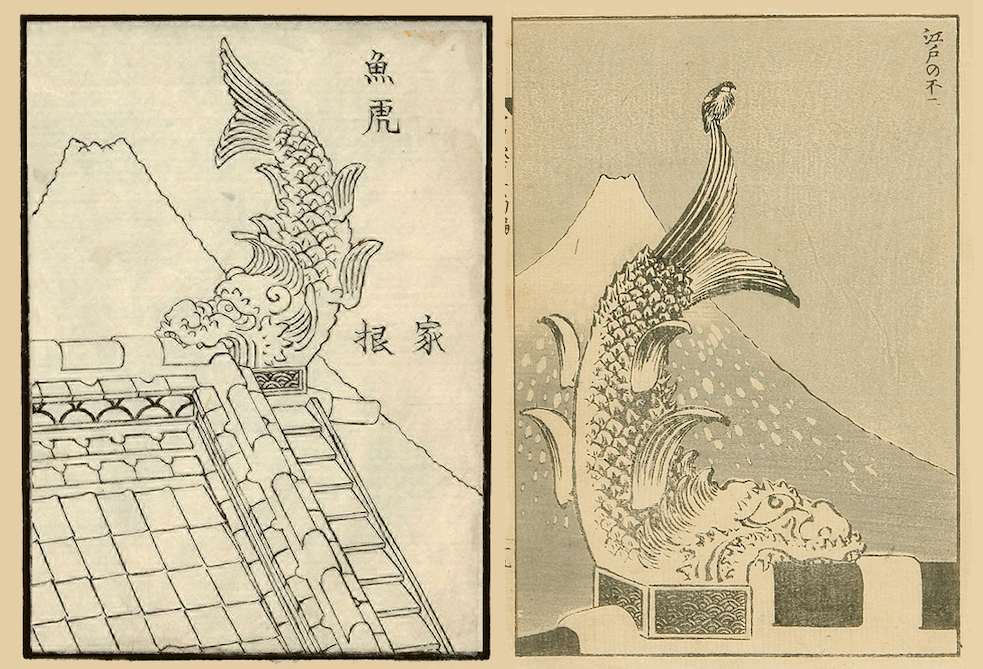

In a great many cases, the details come from Hokusai’s sketchbooks, his Manga, which he published in 15 volumes from 1814-32. The Manga contain drawings of every imaginable subject. Compare the two drawings above. In the initial drawing it is much clearer that the dragon figure is an ornament attached to a roof. We are shown roof tiles and a ladder, which takes us high above the ground. The dragon is conceived as a sea monster, with fish tail, scales and fins. It is an absurd fish out of water, monstrous and humorous at the same time, but exquisitely balanced with a beautiful curve to its body. In the drawing this body opposes the curve of Fuji and hangs in the air free of the mountain’s mass. In the print, the dragon’s body is encased by the mountain (as if the dragon receives its life energy from the mountain) and the curving shapes align. The dragon is larger in the print and the humour is heightened with the addition of a bird perched on the dragon’s tail, making him seem not quite so frightful after all.

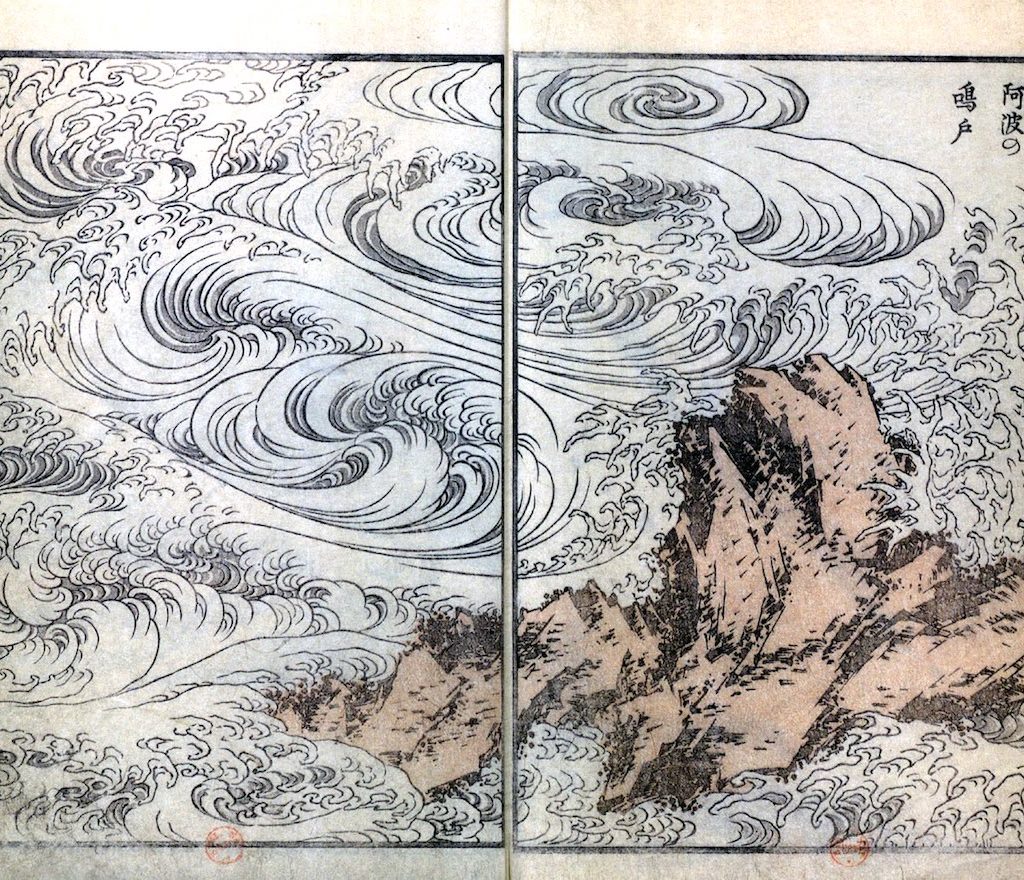

Here is another example from the Manga. Was this scene of storm waves and water crashing on rocks something that Hokusai observed or is he making it all up out of his head? I suspect both are true: Hokusai observed actual storms, but he used his imagination to create the feeling of a storm. Changing seasons and shifts in the weather help give the 100 Views a sense of time passing and epic journey.

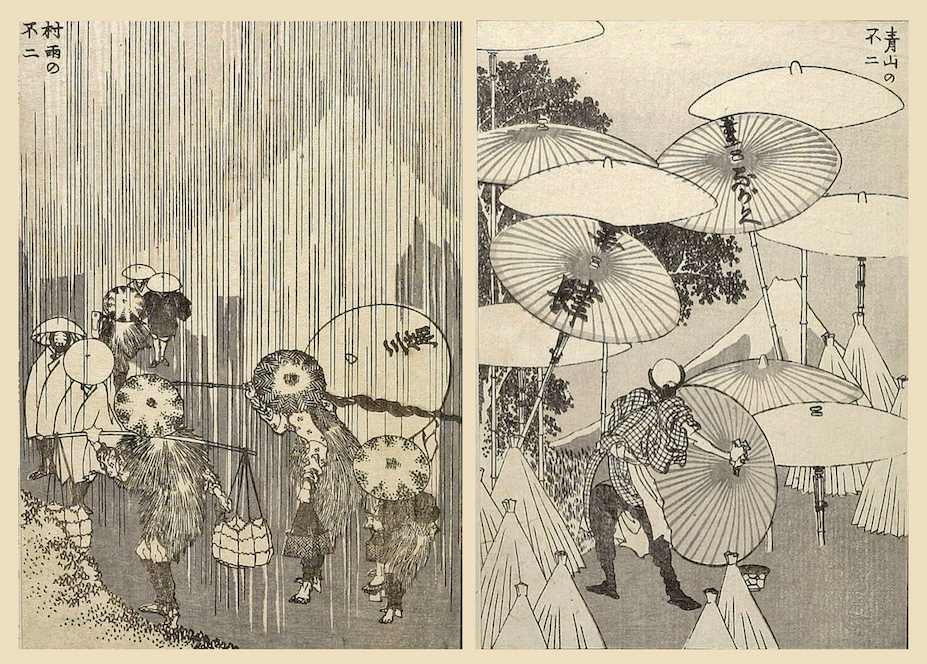

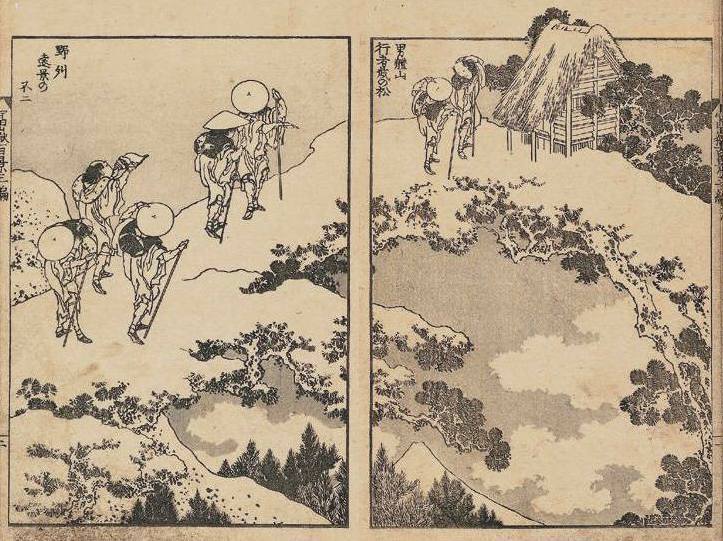

In the image above left, the mountain is barely suggested through sheets of rain, as a procession of travellers recede from view. The image is anticipated earlier in the series when we meet a man selling umbrellas. His display creates a wonderful pattern of overlapping round shapes. As the viewer seeks out Fuji, the collapsed umbrellas in the foreground mimic the mountain’s cone shape and camouflage its presence.

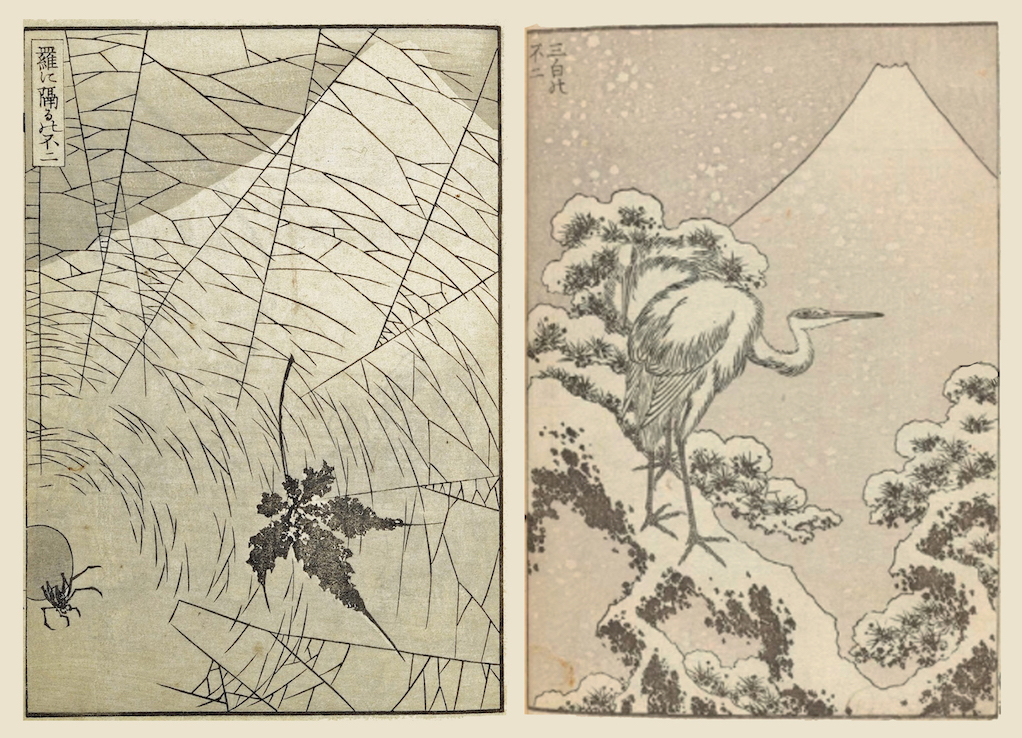

The spider has caught a stray leaf in his web–but it looks as though he’s also caught the mountain. By placing tiny and large together, Hokusai suggests unity to all of nature. Japanese scholar Henry Smith calls this image “visual haiku,” quoting lines from the poet Basho:

Hey spider! How do you sing?

In what key?

Wind of autumn.

I’ve paired this fall scene with a winter scene of a heron perched on the snowy branch of a pine tree. Neither image has a human presence. In the winter picture, Hokusai modified an exercise from Chinese painting: to paint three things all coloured white: usually bird, flower and snow. Hokusai has substituted Fuji for the flower.

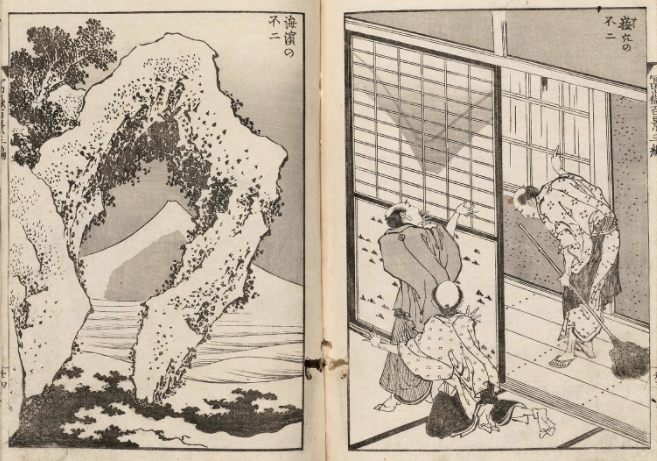

In the image right above, Mt. Fuji projects upside down on a screen inside a house (through a tiny hole in the closed window shutters). This is the camera obscura effect. According to Henry Smith, the Japanese were aware of this effect, but didn’t make use of it as a drawing aid as Western artists did before the invention of photography. On the facing page, Hokusai’s shoreline, strewn with seaweed and waves, shows Fuji through a keyhole-shaped opening in a protruding rock.

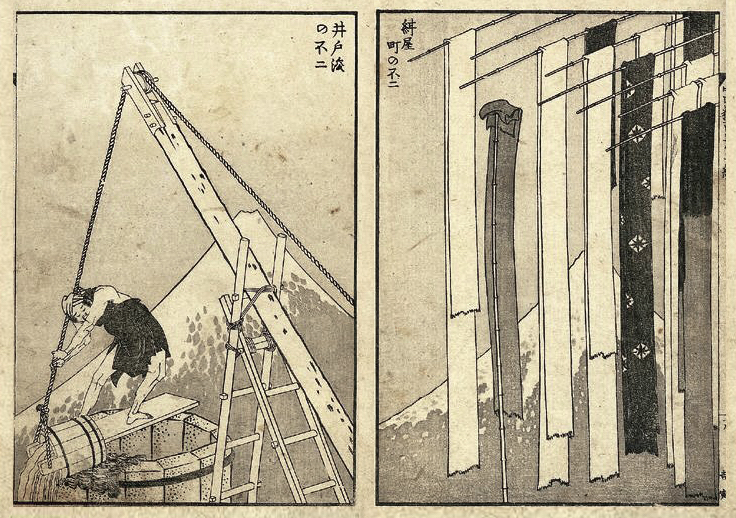

To add variety to his views, Hokusai included a wide array of human activities. Above left, a man cleans out his well. Right, banners that have been freshly dyed, hang to dry in the open air. One fabric is lifted by a stick to its place on the rack. While no person is shown, human activity is evident. The strips of cloth make the picture seem especially tall like the mountain beyond.

A spreading pine–a dense meandering tree–was said to cover a large area on Mt. Nantai. So large was the tree that priests walked along its branches as part of their spiritual practice. Hokusai has turned this legendary pine tree into a fantastic bridge. A shrine is perched along the way, so high it breaks out of the top border of the picture. In an earlier series of travel pictures, Hokusai had featured famous bridges in Japan, but none as whimsical as this. If Fuji appears small at the bottom, it is because Mt. Nantai was 100 miles distant, the furthest vantage point of all the views.

The above image, called “Fuji with a Hat,” reflects the way weather systems gather at the summit of the mountain. In Hokusai’s mind, it’s as though the mountain supports a burden, just as people and domestic animals carry loads on their backs while fording a river. In the distance, oxen carry lumber, a woman with a hoe carries a baby, the woman behind balances a spinning wheel and bundle. In the foreground, a performer supports his dragon costume.

The 100 Views stretch our notions of what is a landscape. Some of the images illustrate stories and legends. Others make humorous analogies or display a kind of visual haiku. Throughout the series, the terrain changes, the weather changes, occupations change, and our views and perceptions change. It would be foolhardy to resist this change. The way the artist hides his mountain from one image to another feels like a game. Hokusai suggests we are all participants in this game and it’s ours to enjoy.