Ads use sophisticated design and clever campaigns to sway human behaviour. But does cleverness and influence make them art? Legendary copywriter Bill Bernbach famously said: “Advertising is persuasion, and persuasion is not a science, but an art. Advertising is the art of persuasion.”

Consider the Michael Kors ad above. Two young women carry Michael Kors purses as they disembark from their private jet while their security man holds off the press. It’s an image of travel and adventure, friendship and freedom. Half fairy tale and half news shot, a document of our times. But wait, it isn’t news, it’s a fabrication that uses models to impersonate celebrities. However, as models, they’ve become rich and famous celebrities in their own right. Fiction imitates life imitates fiction. It’s all very meta … and isn’t that’s the point?

Matt Miller, president of the body that oversees the production of ads in the USA, defines art as “a reflection and expression of what is happening in society.” Society is too complex to understand at any given moment, but perhaps we can understand an ad.

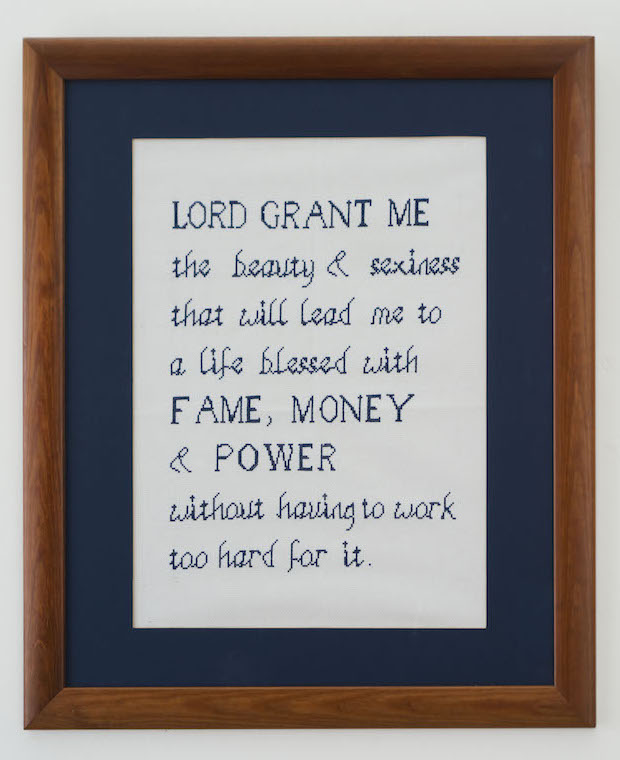

The image below is from artist, Coco Capitán. Born in Seville, Spain, the London Royal College of Art graduate works in a variety of media, moving effortlessly between Fine Art and commercial assignments. Fashion giants Vogue and Gucci are regular clients. The 25-year-old artist likens the fashion house Gucci to the Medici family, famous patrons of Leonardo and Michelangelo in the Italian Renaissance. Her framed prayer is a tongue-in-cheek mission statement for the post-millennials (gen z).

Commercialism is part of Western culture. Ads reflect this. This is what art does, only ads do it in a language that the average person can understand. This argument is countered by Mary Warlick, art historian and executive director of The One Club, a New York trade organization. “Art is visual imagery that is meant to elevate thinking in an aesthetic context. [In contrast] what advertising does is give a visual record of our cultural ambiance and history, our tastes, our trends, our wants, our needs, our buying. It is never meant to elevate us to that higher plane.” Ads may reflect popular currents, but that isn’t the purpose of art, Warlick argues. Art helps us become more self-aware. Art urges us to think more critically and to empathize more with other people. Advertising corrupts thinking and makes us selfish and short-sighted. It makes material things more important than relationships and always suggests there is a shortcut to happiness through the purchase of a product.

Calvin Klein ad featuring artwork by Andy Warhol, 2017. The campaign was called “American classics,” photo by Willy van der Perre

There is common ground in these two arguments. Artists like Andy Warhol, whose artwork appears in the ad above, are not so pure; advertisers are not so impure. To the question, “is advertising art,” author Jonathan Glancey answers: “is art advertising? The simple answer to these questions is that art feeds advertising and vice versa.” (The Independent, July 1995) Artists work on ads, ads feature artwork. Beyond this, there is an enormous gray area where ads and content overlap, such as a beautifully crafted music video that advertises a song. Film trailers are obviously ads, but they need to be clever, fun, exciting, provocative—they need to be artistic—or no one would watch them and share them.

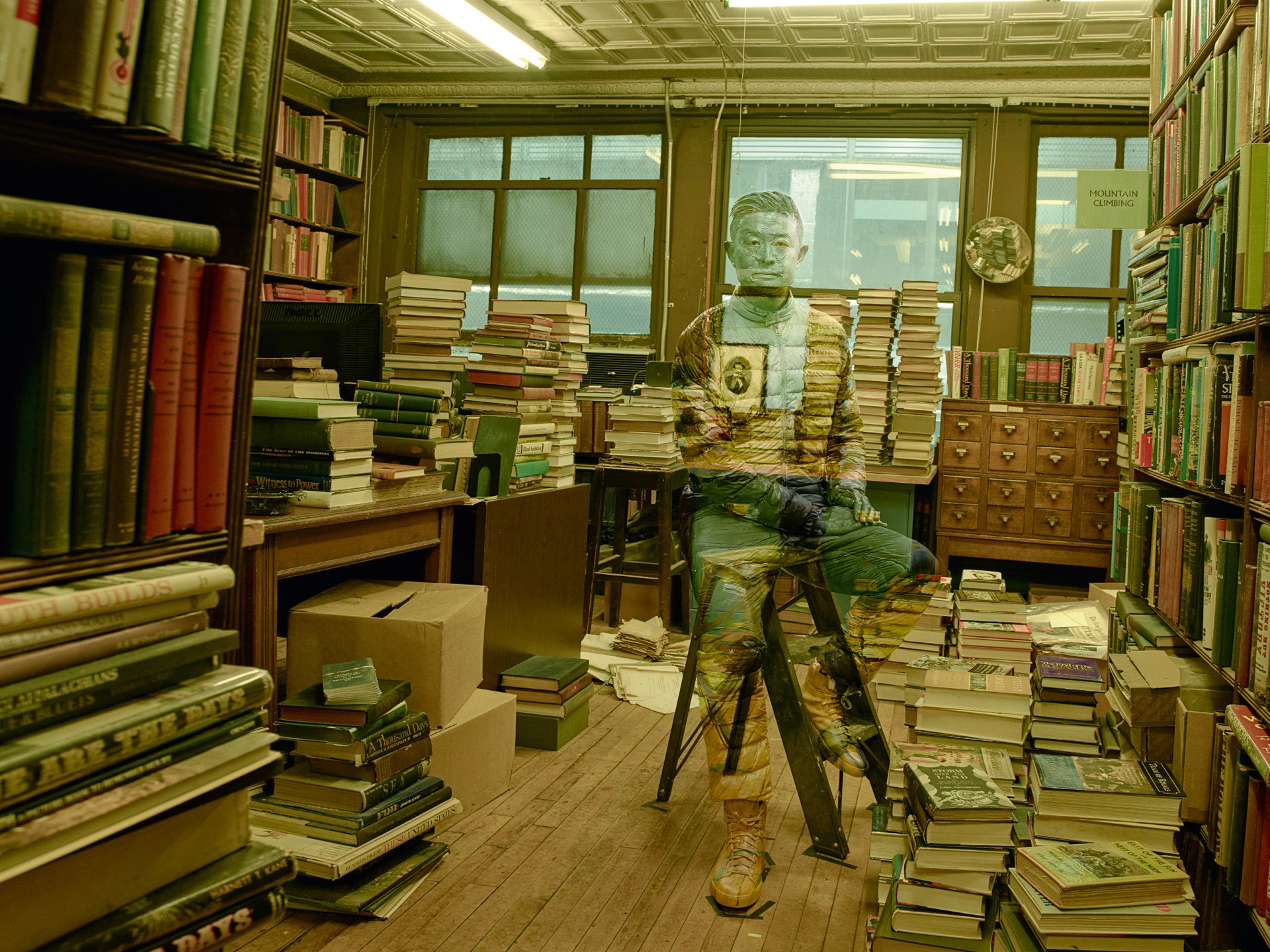

Moncler ad, fall winter 2017, featuring the Chinese conceptual artist Liu Bolin, photo by Annie Leibovitz

The above ad for Moncler’s sporty outdoor wear features Chinese artist Liu Bolan. Bolan is famous for painting his body to match the scene in which he poses, producing an “invisible man” effect. He acts as ghost and silent witness to threatened landscapes and over-looked places–a strange frontman for a fashionable clothing line. What is Bolan’s appeal? He is international, mysterious, a performance artist whose “performance” is a mimicry of his surroundings. Wherever he goes, he fits in. He is a living and breathing work of art. He takes art out of the museum and onto the streets. Moncler jackets are refined like a work of art, but rugged to suit any environment and, when you wear them, you’ll never be out of place.

Western culture is moving in the direction where everyone is an artist, as Joseph Beuys predicted in the 1960s. Technology is key to these new citizen-artists. The trend began one hundred years ago when people purchased low-cost Brownie cameras to record their own lives. Cell phones and social media have taken this home recording to another level of speed and accessibility. Global news increasingly make use of roving amateurs who capture the latest earthquake, protest, rock concert, tsunami or teenage stunt. The smart phone is the on-spot eye-witness to history. On a personal level, we continually revise, update and share family pictures. Ordinary people selectively post selfies and snapshots to promote their most popular and adventurous selves. These are advertisements for ourselves.

The above ad campaign for the South African newspaper, Cape Times, alters famous historic images as if they were selfies rather than documentary photos. Here the reimagined image–a sailor kissing a nurse during the victory celebration that marked the end of WW II, published on the cover of Life magazine in August 1945. The selfie alteration is a funny spin on history. The sailor now kisses the girl for the sake of the camera. Of course selfies did not exist in the 1940s so it creates a magical sense of time travel complete with present-day technology.

This state of citizen-artists continually talking and sharing with one another through media makes us all very art-smart, media-savvy. Ads reflect this desire to be as in-the-know, as mobile, as self-crafting of public image as possible. Everyone is an artist and all images are art because there is no alternative. There is no media innocence in the age of total connectivity.