Who to believe: experts or common sense? The evidence of our senses as we live in the world or the bewildering arguments of rival scientists, journals and institutions? In her 2009 book, Naming Nature, Carol Kaesuk Yoon provides a brief history of taxonomy–the naming and ordering of all life forms–though her captivating story includes questions that touch us all.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a widespread interest in nature led people of all ages and stations in life to scrabble together their own natural history collections. Kings and queens imported elephants and rhinoceroses, parrots and monkeys from distant colonies. The aristocracy planted exotic trees on their estates and grew rare flowers in hothouses. Pressed specimens featured in herbaria. Bottles full of preservatives housed such treasures as the blackbelly triggerfish, armadillos, and fetuses both human and animal. Taverns displayed more outlandish things yet: the penis of a whale, stuffed hummingbirds, snakes from South America, and a starved cat discovered between the walls of Westminster Abbey. As Yoon writes: “The world was full of astonishing things, things that made people desperately curious and to which they felt an easy and intimate connection.”

Yoon introduces a key term in biology, umwelt. This German word literally means “the environment” or “the world around.” For scientists studying animal behavior, Yoon comments, “the umwelt signifies the perceived world, the world sensed by an animal, a view idiosyncratic to each species, fuelled by its particular sensory and cognitive powers and limited by its deficits.” A dog appreciates the world differently from how a bee does or a mole or an earthworm or bacterium. People see the world in their own way as well.

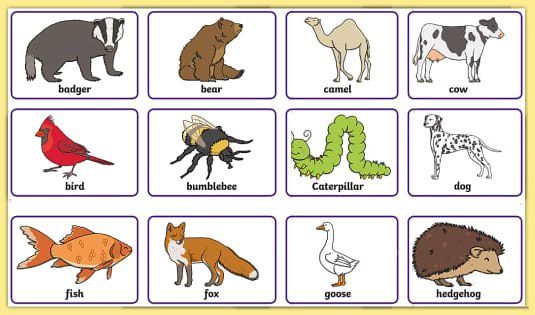

Underlying our vision of the world is a search for order and place. We start by identifying creatures–naming living things, learning about them and gauging their relationship to other like and dislike creatures. One’s umwelt includes a feeling of connection to other living things, as best we see them, and relatedness. This feeling is very strong in us–all cultures name the creatures around them and organize them into groups such as meat eaters or songbirds or fruit-trees. As we observe different life cycles and behaviors, our sense impressions and identification skills form a background of familiar knowledge that is central to our sense of place and well being. It’s one of the first things we teach our children–information they’re eager to learn.

Sadly, as specialists take over, the insatiable curiosity of the public for natural history loses ground or diverts to other areas. Beyond a few animal shows on TV and the dinosaur phase of small children, it’s gotten to the point where the ordinary person can distinguish a “tree” or a “flower,” but couldn’t possibly differentiate one kind from another. This disaffection for nature has come in the midst of the greatest mass extinction of species in the history of the planet. Few people know it’s happening or seem to care, and have no sense of how this loss will affect humanity’s own future.

What has taken its place is our avid differentiation of brands and products. As Yoon writes: “Today, we effortlessly perceive an order among the many different kinds of human-made, purchasable items. Instead of sorting living things by size, shape, color, smell, and sound, we sort merchandise this way, obsessed and immersed as we are in a world of products … We are modern-day hunter-gatherers who do our hunting and gathering, not in the wilds, but at shops and grocery stores.”

It’s not just that specialists have taken over the field of nature. As Yoon outlines, the specialists cannot agree on anything. And one reason they cannot agree is because they are blinded by their umwelt. Human senses are deceiving. For one thing we think of creatures as having fixed, easily identifiable traits and markings. Darwin changed this view. No living thing is fixed; all species vary from one location to another, from one environment to another. The more scrupulous one is in collecting samples, the more these variations will become apparent.

So how to determine where one species starts and another ends? As Yoon outlines, scientists must ignore their umwelt. Instead of relying on observation and instinct, biologists now use statistics, lab tests, genetics and other indicators to place one creature in relationship to another. With all these tools, there is still room to disagree. Taxonomy is not unique in being a discipline marred by dissension, petty feuds and squabbles. I suspect the same holds true of most academic disciplines.

In contrast to the scientists who cannot agree on basic principles, Yoon describes a fascinating experiment conducted by Brent Berlin at the University of California Berkeley. He created a list of bird names and fish names in the language spoken by the Huambisa of the Peruvian rainforest. To get a taste of the experiment, try to distinguish bird from fish in the following lists:

A.

- chunchikit (choon-chew-EE-kit)

- chichikia (Chee-chee-KEE-ah)

- teres (tih-RISS)

- yawarach (yaw-wah-RAHTICH)

- waikia (wa-EE-kee-ah)

B.

- mats (MAW-oots)

- katan (kah-TAHN)

- takaikit (tah-KA-ee-keet)

- tuikcha (too-EEK-cha)

- kanuskin (kah-NOOS-kin)

For the five pairs, here are the bird names: chunchikit, chichikia, takaikit, tuikcha, waikia. How did you do? Quite well, I imagine. That’s because “the bird names are the ones that go tweet, tweet.” Yoon comments: Humans perceive birds in a universally similar way, often named after the sounds they make. Example chickadee.

It’s part of human nature to be curious about nature, to name different species and create a system of order. Learning the names of living beings from culture and tradition helps us relate to those beings, feel they are part of our world. Even if mistakes are made, it’s better to be wrong and invested, than to relinquish the task altogether.

Science may increase knowledge, but not increase how we feel or care about the world. This is why Yoon believes there is still place for folk knowledge, a place for the amateur naturalist and casual observer. “If we hope to revive and save our dying world, to recapture our connection to it, we must breathe a little life back into our vision of it.”