I continue to play with hand-drawn gifs. A dancer turns into a winged creature, veering between cartoon and abstraction. The sequence was first drawn on Flipbook, then modified in Photoshop.

I continue to play with hand-drawn gifs. A dancer turns into a winged creature, veering between cartoon and abstraction. The sequence was first drawn on Flipbook, then modified in Photoshop.

Here’s a great resource for teachers or anyone interested in making quick animations. Flip book! The short animations you make on this site can be saved as GIF files. Many successful gifs are designed so that the end returns to the beginning, making the sequence appear to run in a continuous loop.

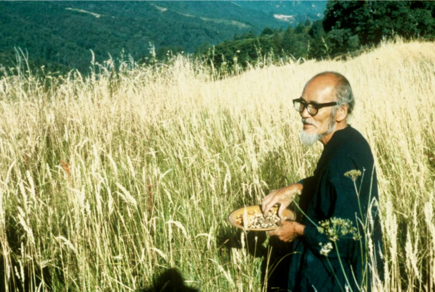

Masanobu Fukuoka (1913-2008) was a visionary ecologist, farmer and author. His pursuit of a balanced life within a healthy productive environment was carried out on a small scale, but with an originality and defiance of accepted wisdom that has inspired others around the world. “The ultimate goal of farming,” Mr. Fukuoka says, “is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” (One Straw Revolution, p. xiv)

Masanobu Fukuoka (1913-2008) was a visionary ecologist, farmer and author. His pursuit of a balanced life within a healthy productive environment was carried out on a small scale, but with an originality and defiance of accepted wisdom that has inspired others around the world. “The ultimate goal of farming,” Mr. Fukuoka says, “is not the growing of crops, but the cultivation and perfection of human beings.” (One Straw Revolution, p. xiv)

Fukuoka began his career as a scientist based in Yokohama working for the Japanese government. He researched ways of combatting diseases in valuable agricultural crops. He was happy and successful. Then, while still a young man, he was hospitalized with pneumonia. During his recovery, he had a spiritual awakening, which led him to question everything he had previously been taught. He scoured the countryside in search of traditional farms, asking about farming methods before the arrival of modern chemicals and large machinery. Could it be that the technology used in industrial farming was creating more problems than it solved? Were the designers of ever-more powerful fertilizers, pesticides and genetically-modified crops moving in the wrong direction? Was there an alternative path that would not be so disruptive of native eco-systems?

Fukuoka resigned his government position to become a farmer, moving back to his father’s farm on the southern island of Shikoku to take care of a hillside orchard. Here Fukuoka applied traditional non-invasive approaches to growing fruit and rice. News of his unusual methods spread and visitors began arriving at his farm, many of whom became volunteer workers. Teaching these young recruits led Fukuoka to jot down his ideas. The resulting book, One Straw Revolution, published in 1975, was an astonishing statement of a creed of simplicity and adherence to natural ways.

In his preface to the English language edition that appeared in 1978, poet and activist Wendell Berry comments: “Mr. Fukuoka has understood that we cannot isolate one aspect of life from another. When we change the way we grow our food, we change our food, we change society, we change our values. And so this book is about paying attention to relationships, to causes and effects, and it is about being responsible for what one knows.” (p. xii)

Here is a sampling from the book. I start with Fukuoka’s contrast of his own traditional farm with that of a modernized neighbouring farm.

“Make your way carefully through these fields. Dragonflies and moths fly up in a flurry. Honeybees buzz from blossom to blossom. Part the leaves and you will see insects, spiders, frogs, lizards, and many other small animals bustling about in the cool shade. Moles and earthworms burrow beneath the surface. This is a balanced rice field ecosystem. Insect and plant communities maintain a stable relationship here. It is not uncommon for a plant disease to sweep through the area, leaving the crops in these fields unaffected.

“And now look over at the neighbor’s field for a moment. The weeds have all been wiped out by herbicides and cultivation. The soil animals and insects have been exterminated by poison. The soil has been burned clean of organic matter and micro-organisms by chemical fertilizers. In the summer you see farmers at work in the fields, wearing gas masks and long rubber gloves. These rice fields, which have been farmed continuously for over 1,500 years, have now been laid waste by the exploitive farming practices of a single generation.”

Fukuoka goes on to outline the core ideas that differentiate his approach from large commercial practices. He calls these the “four principles of natural farming.”

“The first is no cultivation, that is, no plowing or turning of the soil. For centuries, farmers assumed that plowing is essential for growing crops. However, non-cultivation is fundamental to natural farming. The earth cultivates itself naturally be means of the penetration of plant roots and the activities of micro-organisms, small animals and earthworms. The second is no chemical fertilizer or prepared compost. People interfere with nature, and, try as they may, they cannot heal the resulting wounds. The third is no weeding by tillage or herbicide. Weeds play their part in building soil fertility and in balancing the biological community. As a fundamental principle, weeds should be controlled, not eliminated. Straw mulch, a ground cover of white clover interplanted with the crops and temporary flooding provide effective weed control in my fields. The fourth is no dependence on chemicals. From the time that weak plants developed as a result of such unnatural practices as plowing and fertilizing, disease and insect imbalance became a great problem in agriculture. Nature, left alone, is in perfect balance.” (p. 33-34)

In the middle of his book, Fukuoka discusses the need for rethinking long-standing harmful practices. He points out that once a practice becomes habitual, no matter how ineffective it proves, people have trouble changing course because their minds have grasped hold of a fixed idea that seems all but unshakable.

“To the extent that the consciousness of everyone is not fundamentally transformed, pollution will not cease.” (p. 82)

“When a decision is made to cope with the symptoms of a problem, it is generally assumed that the corrective measures will solve the problem itself. They seldom do … Until the modern faith in big technological solutions can be overturned, pollution will only get worse.” (p. 84)

In the final section to his book, Fukuoka turns his attention to the subject of food. He argues that people’s diets are unhealthy because they are based on ill-conceived notions of what is and isn’t tasty. The prejudice against simple natural foods is an acquired cultural absurdity.

“A natural person can achieve right diet because his instinct is in proper working order. He is satisfied with simple food; it is nutritious, tastes good , and is useful daily medicine.Food and the human spirit are united. ” (p.136)

“Modern people have lost their clear instinct … They go out seeking a variety of flavours. Their diet becomes disordered; the gap between likes and dislikes widens, and their instincts become more and more bewildered. At this point people begin to apply strong seasoning to their food and to use elaborate cooking techniques, further deepening the confusion. Food and the human spirit have become estranged.” (p. 136)

“People nowadays eat with their minds, not with their bodies … Foods taste good to a person not necessarily because they have nature’s subtle flavours and are nourishing to the body, but because his taste has been conditioned to the idea that they taste good.” (p. 137)

Even by the standards of most conscientious organic farmers, Fukuoka’s methods often appear radical. Critics view his ideas as impractical or unsuited for Western climates and conditions. Fukuoka counters that his methods are not quick easy fixes. Patience and experimentation are required. What Fukuoka has achieved is help spark a debate about food and land use, a debate which gains in relevance as concerns mount over the health risks of GMOs, pesticides and land depletion. Fukuoka is now regarded as a pioneer of the permaculture movement. His vision of farming as a seeking of balance in a larger ecosystem offers a healthy alternative to the destructive practices that are currently employed.

I had this conversation with a young person the other day.

Doug: Why not? I grew it myself in my own garden.

Doug: I’ll wash it off.

Doug: That’s the way things grow. Soil, water, sunlight. Fertilized by you know what.

Doug: Well, Precious, where does your food come from?

Young Person: You really want to know? I can’t believe this! It’s like I’m talking to a child. See this. (points to a bag of cookies) It’s clean. No dirt! And it tastes good. It has a brand name everyone’s heard of so you know that it’s safe.

Our conversation breaks off here. We go our separate ways, convinced the other is a lost cause. The young person believes food grows in plastic bags with fancy labels, protected by factory protocols from such harmful things as the outdoors and natural elements. For my part, I think such humble things as soil, water and sunlight may be essential for the growth of food. Furthermore I believe it’s unwise to despise the very things that are essential to us.

My conversation with the young person is complicated by two additional factors: religion and psychology. Sociologist Mary Douglas tells us that eating habits reflect religious values. If you’re an ecologist, then industrial farming, genetically modified food and fast food are abhorrent evils. If you worship technology, pop culture and mass media, then you’re likely to scoff at traditional farming methods, organic food, sit-down meals and eating with your family. Fast food goes hand in hand with the belief that what God wants for you is to make your life as easy and convenient as possible, especially in the short term. People’s accelerated eating habits mirror a revolution in people’s religious thinking. We no longer “reap what we sow.” Instead “we deserve a break today.”

How can two sides have a conversation when each side feels their religious values and indeed their very sanity is being called into question? Freud coined a phrase “reality testing,” which he claimed each of us do all the time. We are constantly testing ideas and images with everyday experience. This is not to say we don’t fool ourselves and make up crazy justifications for foolish actions. You might say every act and exchange is a kind of test, but we fudge the results. We cheat, misread and ignore the results of our tests. Freud believed that the perpetual cheaters developed nervous disorders. He believed this could happen to cultures and to societies as well as to individuals.

Is there any way we can reality-test our food, religion, sanity debate? One test could be: try growing your own food. Try growing food outdoors in soil; try growing food indoors without soil, water or sun. We can give a name to this test: self-reliance. Why is self-reliance important? It’s an aid to survival. It develops character and self-confidence. It provides an individual with a solid foundation from which to grow. The opposite of self-reliance is dependence on others. In a specialized world, we all come to depend upon the services of others. But with this dependence, we learn to be critical, to compare services and costs. We share notes with our friends and join networks. We are vigilant to avoid scams and traps. When we receive bad service, we protest and boycott. In short, we become wary and diligent shoppers. This is another form of reality-testing.

In a complex world, we need both forms. We need to do things for ourselves and when it’s not practical to do this, we need to join networks that engage in critical evaluation. The young person and myself, we may not always agree on our food, but I hope that we can agree that helplessness, isolation and uncritical thinking are harmful ways of being. When we agree on the importance of productive and active reality-testing then we can start to join together and build a truly healthy community.

When it was announced this week that short-story specialist Alice Munro had won the Nobel Prize for literature, Canadians from coast to coast shook their heads in wonder and smiled inwardly with deep satisfaction. Canada has produced many great writers, but no other writer has such unequivocal support or is more admired than Alice Munro. She writes with modesty, with precision, with insight into human character and has the skill to evoke a powerful range of feelings with subtlety and nuance. She is truly Canada’s Chekhov.

The following quote by Munro has appeared in just about every tribute and news-story about the author: “I want to tell a story in the old-fashioned way—what happens to somebody—but I want that ‘what happens’ to be delivered with quite a bit of interruption, turnarounds, and strangeness. I want the reader to feel something is astonishing—not the ‘what happens’ but the way everything happens.”

But how exactly does Munro achieve this? I approach this question by looking at two stories about neighbors, “The Shining Houses” (from Dance of the Happy Shades, 1968) and “Fits” (from The Progress of Love, 1985). One is the story of the cruelty of supposedly good people; the other traces a town’s reaction to the murder/ suicide of an elderly couple. Both stories have an outward action and an inward action. Events trigger reactions and it is the contemplation of these reactions that awaken a new sense of understanding in the central characters.

“The Shining Houses” has a single narrator and the story revolves around her sudden awareness of the vulnerability of an individual who stands apart from the impulses of the community. In a neighborhood that is being gentrified, rapidly changing from sparse unkempt hobby-farms to densely-packed suburb with well-attended gardens and manicured lawns, one old lady who refuses to change is seen as a bothersome nuisance; her home is an eyesore to the movement of progress. A plan is put in place to evict the old lady and have her house torn down. The narrator sees the callousness of this scheme, and the uncharitable lack of sympathy for someone who represents part of the history of the place. The new neighbors act selfishly, but disguise this self-interest as community virtue. This is how Munro describes it: “And these were joined by other voices; it did not matter much what they said as long as they were full of self-assurance and anger. That was their strength, proof of their adulthood, of themselves and their seriousness. The spirit of anger rose among them, bearing up their young voices, sweeping them together as on a flood of intoxication, and they admired each other in this new behaviour as property-owners as people admire each other for being drunk.”

When the narrator refuses to go along, she realizes, as an individual acting in opposition to the group, she opens herself up to a similar kind of targeting. So why does she take the oppositional stance that she does? She is powerless to help the old lady who will be evicted. She has no influence within the group. Still there is a sense that by voicing her opposition, she has performed a small act of courage and held true to her own conscience. She may pay a price for this in the future. In fact that price has already begun as the narrator starts to separate herself from the others in her mind.

“Fits” has a more complex structure with its diverse narrators and multiple back-stories. Reactions to an unexpected and gruesome crime reveal striking differences among the characters, whose values are shaped by long-ago events. A husband thinks back on his former love affairs with married women, affairs he now regards as an avoidance of reality. Munro writes: “‘There are things I just absolutely and eternally want to forget about,’ Robert had told Peg. He talked to her about cutting his losses, abandoning old bad habits, old deceptions and self-deceptions, mistaken notions about life, and about himself. He said that he had been an emotional spendthrift, and had thrown himself into hopeless and painful entanglements as a way of avoiding anything that had normal possibilities. That was all experiment and posturing, rejection of the ordinary, decent contracts of life. So he said to her. Errors of avoidance, when he had thought he was running risks and getting intense experiences.”

Tiring of these passionate but difficult entanglements, the man marries a practical woman who shares his desire for a home and family. Unfortunately, his wife lacks imagination, as well as the ability to share her deepest feelings with others. This failing becomes glaringly clear after the wife discovers the bodies of the murdered couple. The wife informs the police but neglects to tell a single member of her own family of her horrific discovery, nor does she confide to them any sense of her reaction to this shattering event.

The way people talk and interact with one another is one of Munro’s chief concerns, the bridges and barriers created by the slightest of gestures. She sets up the differences between husband and wife like this: “His friendliness and obligingness were often emphatic, so that people might get the feeling of being buffeted from all sides. This is a manner that serves him well in Gilmore, where assurances are supposed to be repeated, and in fact much of the conversation is repetition, a sort of dance of good intentions, without surprises.” In contrast to the husband’s garrulousness is his wife’s reserve. “Peg smiled as she would smile in the store when she gave you your change–a quick transactional smile, nothing personal … Robert once told her he had never met anyone so self-contained as she was. (His women have usually been talkative, stylishly effective, though careless about some of the details, tense, lively, ‘interesting.’) Peg said she didn’t know what he meant.”

The husband contrasts his wife’s non-reaction to the crime to the over-reaction of the town’s people who can’t stop talking about the murdered couple and the possible motives for why it happened. The husband is aware of his own over-active imagination. It’s a flaw, but at least it is one he’s able to share, along with his struggle to manage it in appropriate ways. After a long winter walk, he decides to return to his wife, though he remains troubled by her cool demeaner.

The story ends with new information, information unknown to the husband. This information suggests the wife was indeed affected by the scene she witnessed. She was so affected that she lied about certain details in order to cover-up what she went through. The husband doubts his wife, but his understanding of her is incomplete and imperfect. This is where the story ends, with doubts, lies, and an imperfect understanding of the other. It is not the murder that is strange in this story; it is the way the murder leads to a maze of unexpected connections and misconnections, misgivings and unresolved needs, among the seemingly unimportant characters.

I’m tempted to link Munro to the movement of Magical Realism often associated with Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, Salmon Rushdie, and other writers who mix fantastic elements into otherwise closely observed and detailed stories. While Munro’s prose is not as saturated and flowery as these more ‘tropical’ writers—she has that Northern coolness of temperament—two key features of Magical Realism abound in her work: the multi-layered stories-within-a-story and the presence of ghosts. By ghosts I mean the sudden (often inconvenient) eruption of the past into the present and the feeling of characters being haunted by a force not known or knowable by others.

In the stories I’ve cited, the evicted woman in “The Shining Houses” serves as a kind of ghost and she affects the narrator in ways that her other neighbors will never understand. The evicted woman is the only character with a back-story, which tells of a ghost-like husband who abandoned her. Munro has her narrator uncover this fact: “She did not talk to many old people any more. Most of the people she knew had lives like her own, in which things were not sorted out yet, and it is not certain if this thing, or that, should be taken seriously. Mrs. Fullerton had no questions of this kind. How was it possible, for instance, not to take seriously the broad back of Mr. Fullerton, disappearing down the road on a summer day, not to return? ‘I didn’t know that,’ said Mary. ‘I always thought Mr. Fullerton was dead.” “He’s no more dead than I am,’ said Mrs. Fullerton, sitting up straight … ‘he’s just gone off on his travels, that’s what he is.'” The old woman refuses to move from her rundown house because otherwise how will the ghostly husband ever find her? The eviction, which she does not know is in the works, will cause a metaphysical rupture from which it is unlikely she will recover. This is the purpose of the ghost.

“Fits” draws its title from a theory advanced by the character Robert: people behave like landscapes that are prone to periodic earthquakes, eruptions, and other fits, the causes of which are largely hidden and invisible. The ghost in this story is also a husband who has deserted his wife and disappeared in search of a place that is equal to his imagination. The ghostly husband represents the need for imaginative or psychic connection with another person. Without this, one encounters the ghost state of metaphysical rupture. Robert has taken the ghostly husband’s place and sees a similar dilemma opening up before him. “A man doesn’t just drive farther and farther away in his trucks until he disappears from his wife’s view. Not even if he has always dreamed of the Arctic. Things happen before he goes. Marriage knots aren’t going to slip apart painlessly, with the pull of distance. There’s got to be some wrenching and slashing.” Fits of strangeness reveal the truth that any life contains its fair share of secrets and scars that can never be entirely erased, as well as images and emotions that cannot be communicated adequately from one person to another.

I’d like to thank my sister Janet Pope for suggesting the topic of this post and for lending me copies of the two stories by Alice Munro. Along with the books, Janet wrote me the following note to add to this blog:

“Like an archaeologist assigned an unpromising site, Alice Munro takes ordinary people and starts digging through layers, accumulations, detritus of the past till she uncovers evidence of a richly imagined life. This patient exploration in story after story changes the reader. She enlarges the assumptions we had about others which are usually narrow and static. She makes us see that people are endlessly complex, ‘moving out of their prisons, showing powers we never dream they have.’ Through the Munro process, we, as ‘ordinary people,’ learn to recognize and respect our subterranean depths.”

Slow and meticulous, almost clinical in his approach to art, Alex Colville is not thought of as a spontaneous reporter embedded in the thick of action. Yet this is precisely how he started his career, going directly from art school to the battlefields of WW II. His deployment as war artist in 1944 took the budding Canadian artitst overseas for 18 months. Colville’s book, Diary of a War Artist, testifies to the formative nature of this experience. One of the lessons Colville learned was that a detached point-of-view that eschews overt emotion paradoxically adds to the viewer’s emotional experience of the work. Colville also sensed that in wartime mundane actions take on an inordinate importance for soldiers involved in dangerous and uncertain missions. These lessons were unexpectedly confirmed after the war when Colville found time to visit the major art galleries of Holland. Here he encountered Dutch Baroque art and recognized in deHooch and Vermeer two kindred spirits. Colville saw how these artists turned away from the exoticism, violence and supernatural elements of Biblical stories, replacing this external drama with an internal drama that recognizes in daily life its own mystery and significance.

Art critic Tom Smart has defined one of Colville’s most important themes: the need for order in a world that threatens to disintegrate into chaos at any moment. Many commentators use the words “anxiety” and “alienation” when describing Colville’s work. Yet it is hard to say just where or how this anxiety arises. The faces of figures are often hidden or obscured, creating a mask-like effect that adds mystery and intrigue to the image. While the action depicted in the image is often frozen, the composition is so precisely worked out that there is an unconscious feeling that if anything moves the delicate balance will be marred or revoked.

In his exhibition catalogue Alex Colville: Return (Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2003), Tom Smart notes how animals in Colville’s work function as surrogates for the artist. There is undeniably a close relationship of people and animals in these images. To the point that Colville portrays domestic animals with a seriousness, sensitivity and rapport rarely seen in the history of Western art. What makes the artist’s rapport with animals so unique is the way he suggests that animals sense the world differently than people do. In many cases, animal senses may be more acute and perceptive than human senses and faculties of recognition.

One of my own life goals is to increase my appreciation of the world I inhabit, to cultivate a finer awareness of the things around me. Colville suggests that animals have an extraordinary awareness of the world around them. They are curious and alert seekers. People empathize with animals and are able to share their experiences as co-adventurers. Colville uses animals to suggest the expansion of consciousness through empathy with another creature. But at the same time humans are clearly separate from animals and the recognition of this separation is a reminder of the inherent limitation of our consciousness.

“Colville has said: ‘I am inclined to think that people can only be close when there is some kind of separateness.’ When he says this, Colville does not mean the egotism of ‘having one’s own space,’ but rather the responsibility of caring for the individuality of the other.” (Burnett 1983: 108). In his essay, Alex Colville: Doing Justice to Reality, anthropology professor David Howes concludes: “the Canadian soul is never at one with itself: its “integration” is contingent upon being juxtaposed to some double, as in Colville’s couples [or human/ animal pairs]. In Canada, the minimal conceptual unit is a pair as opposed to a one.”

It is this double solitude, empathy combined with an acceptance and respect for difference, that underlies most of Colville’s paintings featuring animals and people. Colville uses animals as agents helping us increase our awareness of the world, as well as teaching us to tolerate difference and appreciate aspects of the world that are beyond our understanding.

Kathleen read me this poem last night from one of May Sarton’s journals (After the Stroke):

I see that age will make my hands a sieve/ But for a moment the shifting world suspends/ its flight and leans toward the sun once more/ as if to interrupt its mindless plunge/ through works and days that will not come again./ I hold myself immobile in bright air/ sustained in time astride the flying change. — Henry Taylor

It made me think of forces I cannot control. Getting into a mind space where I am less of a control freak, where I just allow things to happen, accept the things that do happen, while also contributing to making things happen. To participate in the forces of change enjoying both “the moment the shifting world suspends” and the “mindless plunge” alike.

A long overdue post about Nova Scotian artist and poet Joanne Light whose exhibition of images and texts was recently held in Halifax at the Unitarian Church Hall. The series of brightly-coloured paintings emerged from the memory of a childhood struggle with the concepts of good and evil. These concepts were introduced in terrifying hell-fire sermons that both mesmerized and bewildered Joanne as a child. In her exhibition, Joanne draws in the style of her younger self as she tries to exorcise demons from the past. The exercise is filled with humour, as allusions to pop culture and invented characters spring up along the way. Accompanying each image are texts in poetry and prose. For the opening of the exhibition, the artist skillfully blended words and images in a performance accompanied by slide projections.

Joanne Light has worked as a teacher and writer in various parts of Canada, including several years in Northern communities. Her interest in landscape and geography is apparent in both her poetry and her visual imagery.

Tom Ripley is a counterfeiter, con artist and murderous anti-hero, yet his journey of self-discovery is strangely compelling in Patricia Highsmith’s gripping crime novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley, first published in 1955. There are many ways to regard this novel: as a portrait of human pathology, as an adventure story, as a travelogue, as a critique of American values of the 1950s. Today I approach this novel as part of a series of blogs on water imagery and symbolism in art & literature.

The cover of the first edition gives some hint to the meaning of water in the novel. It serves as a barrier separating characters, preventing their understanding of one another. Water also runs a meandering, unpredictable course–like the twisting plot that features false identities, murder, pursuit and cover-up.

Early in the novel, Highsmith upsets expectations of water signifying anything romantic. “The atmosphere of the city became stranger as the days went on … As if when his boat left the pier on Saturday, the whole city of New York would collapse with a poof like a lot of cardboard on a stage. Or maybe he was afraid. He hated water. He had never been anywhere before on water, except to New Orleans from New York and back to New York again, but then he had been working on a banana boat mostly below deck, and he had hardly realized he was on water. The few times he had been on deck the sight of the water had at first frightened him, then made him feel sick, and he had always run below deck again, where, contrary to what people said, he had felt better. His parents had drowned in Boston harbour, and Tom had always thought that had something to do with it, because as long as he could remember he had always been afraid of water, and he had never learned how to swim.” (p. 25)

The Queen Mary steaming down the Hudson River in 1946. Tom would have boarded a similar ship on his passage to Europe. Photo by Andreas Feininger

The author connects water in Tom’s mind with childhood trauma. But the ocean voyage also has a liberating effect on Tom. “He began to play a role on the ship, that of a serious young man with a serious job ahead of him … He was starting a new life. Goodbye to all the second-rate people he had hung around and had let hang around him in the past three years in New York. He felt as he imagined immigrants felt when they left everything behind them in some foreign country, left their friends and their relations and their past mistakes, and sailed for America. A clean slate!” (p. 34-35)

The story reflects aspects of Highsmith’s own life. Her self-exile from the USA, restless travels, learning languages, making new friends and growth as a writer. The excitement of fresh encounters is tempered by memories of an unhappy childhood and the persecution she felt living as an openly gay woman in McCarthy-era America. She spent time in Mexico, Italy, and France before settling in Switzerland and finding a receptive ear at the Swiss publishing house Diogenes Verlag.

In Highsmith’s novel, the first function of water is to separate the characters into two realms: the worldly but rootless Europeanized Americans and the vulgar money-making stay-at-home Americans. The next function of water is to set Tom on his way to discovering what kind of person he is, identifying and developing his own unique talents. This is the classic hero’s journey, something the reader might well identify with. Perversely Tom’s talents involve lying, deception and murder–all socially unacceptable traits. Tom tries to fit in with the people he encounters, and is stung by their rejection of him. The rejection is largely based on class prejudice. Tom is not rich and independent like the others. He does not own a yacht. He lacks their education and knowledge of art and foreign languages. However he is a quick study and is able to mimic their ways quite easily. At first this mimicry amuses the superficial young aristocrats, who nonetheless feel themselves to be innately superior to Tom. This smug superiority arouses a murderous resentment.

The novel changes moods abruptly. These changes often occur around water. The first murder takes place on water. Tom Ripley kills a man, but has trouble disposing of the body. In the process Tom is accidently knocked overboard. “He was in the water. He gasped, contracting his body in an upward leap, grabbing at the boat. He missed. The boat had gone into a spin. Tom leapt again, then sank lower, so low the water closed over his head again with a deadly fatal slowness, yet too fast for him to get a breath, and he inhaled a noseful of water just as his eyes sank below the surface. The boat was farther away. He had seen such spins before: they never stopped until somebody climbed in and stopped the motor, and now in the deadly emptiness of the water he suffered in advance the sensations of dying, sank threshing below the surface again, and the crazy motor faded as the water thugged into his ears, blotting out all sound except the frantic sounds that he made inside himself, breathing, struggling, the desperate pounding of his blood.” (106-107)

This terrible scene is followed by a couple of pages detailing Tom’s escape from death and his recuperation in a nearby town. He boards a train and feels himself begin to change. “The white, taut sheets of his berth on the train seemed the most wonderful luxury he had ever known. He caressed them with his hands before he turned the light out. And the clean, blue-grey blankets, the spanking efficiency of the little black net over his head–Tom had an ecstatic moment when he thought of all the pleasure that lay before him now … other beds, tables, seas, ships, suitcases, shirts, years of freedom, years of pleasure. Then he turned the light out and put his head down and almost at once fell asleep, happy, content, and utterly, utterly confident, as he had never been before in his life.” (p. 111-112)

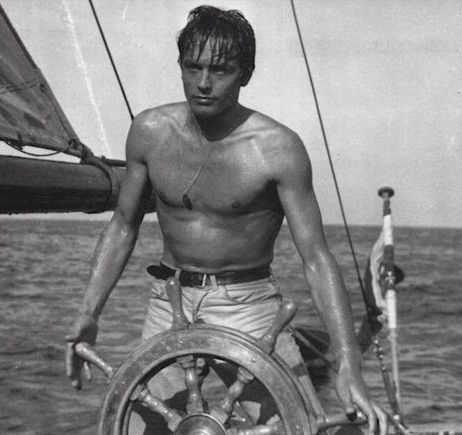

Actor Alain Delon plays Tom Ripley in the French film, Plein Soleil, 1960 (directed by René Clément), the first of many adaptations of The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Water suggests a reversal of fortunes. From grovelling subservience to wealthy independence. A powerless working-class youth, unrecognized by the world, becomes a resourceful self-confident criminal. But Tom’s confidence periodically gives way to paranoia. Just as water covers up evidence of Tom’s crime, the fear arises that either the body or the stolen boat will wash ashore or resurface in some incriminating way. It is part of Highsmith’s perverse genius that she encourages the viewer to root for the villain, to cheer when he eludes capture, keeping this addictive story going.

The novel ends as it begins on a passenger ship. The sea as barrier and divider of people, as deadly, deceptive, ever-changing in its moods, is an appropriate symbol for this reckless adventurer who counts on luck and his own devious improvisational skills to make his way in the world.