Slow and meticulous, almost clinical in his approach to art, Alex Colville is not thought of as a spontaneous reporter embedded in the thick of action. Yet this is precisely how he started his career, going directly from art school to the battlefields of WW II. His deployment as war artist in 1944 took the budding Canadian artitst overseas for 18 months. Colville’s book, Diary of a War Artist, testifies to the formative nature of this experience. One of the lessons Colville learned was that a detached point-of-view that eschews overt emotion paradoxically adds to the viewer’s emotional experience of the work. Colville also sensed that in wartime mundane actions take on an inordinate importance for soldiers involved in dangerous and uncertain missions. These lessons were unexpectedly confirmed after the war when Colville found time to visit the major art galleries of Holland. Here he encountered Dutch Baroque art and recognized in deHooch and Vermeer two kindred spirits. Colville saw how these artists turned away from the exoticism, violence and supernatural elements of Biblical stories, replacing this external drama with an internal drama that recognizes in daily life its own mystery and significance.

Art critic Tom Smart has defined one of Colville’s most important themes: the need for order in a world that threatens to disintegrate into chaos at any moment. Many commentators use the words “anxiety” and “alienation” when describing Colville’s work. Yet it is hard to say just where or how this anxiety arises. The faces of figures are often hidden or obscured, creating a mask-like effect that adds mystery and intrigue to the image. While the action depicted in the image is often frozen, the composition is so precisely worked out that there is an unconscious feeling that if anything moves the delicate balance will be marred or revoked.

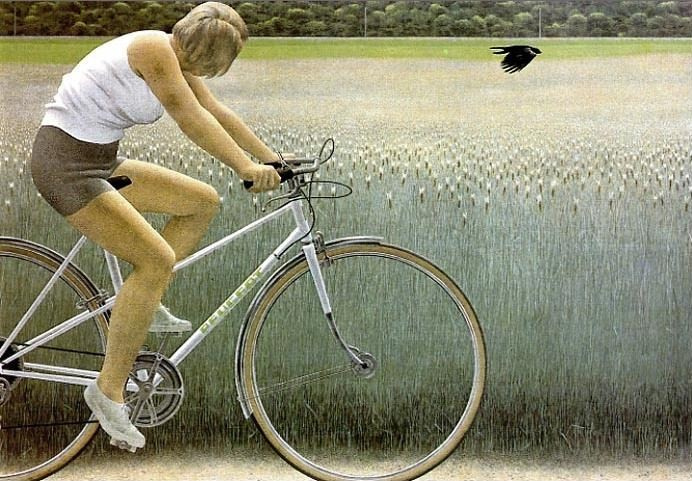

In his exhibition catalogue Alex Colville: Return (Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, 2003), Tom Smart notes how animals in Colville’s work function as surrogates for the artist. There is undeniably a close relationship of people and animals in these images. To the point that Colville portrays domestic animals with a seriousness, sensitivity and rapport rarely seen in the history of Western art. What makes the artist’s rapport with animals so unique is the way he suggests that animals sense the world differently than people do. In many cases, animal senses may be more acute and perceptive than human senses and faculties of recognition.

One of my own life goals is to increase my appreciation of the world I inhabit, to cultivate a finer awareness of the things around me. Colville suggests that animals have an extraordinary awareness of the world around them. They are curious and alert seekers. People empathize with animals and are able to share their experiences as co-adventurers. Colville uses animals to suggest the expansion of consciousness through empathy with another creature. But at the same time humans are clearly separate from animals and the recognition of this separation is a reminder of the inherent limitation of our consciousness.

“Colville has said: ‘I am inclined to think that people can only be close when there is some kind of separateness.’ When he says this, Colville does not mean the egotism of ‘having one’s own space,’ but rather the responsibility of caring for the individuality of the other.” (Burnett 1983: 108). In his essay, Alex Colville: Doing Justice to Reality, anthropology professor David Howes concludes: “the Canadian soul is never at one with itself: its “integration” is contingent upon being juxtaposed to some double, as in Colville’s couples [or human/ animal pairs]. In Canada, the minimal conceptual unit is a pair as opposed to a one.”

It is this double solitude, empathy combined with an acceptance and respect for difference, that underlies most of Colville’s paintings featuring animals and people. Colville uses animals as agents helping us increase our awareness of the world, as well as teaching us to tolerate difference and appreciate aspects of the world that are beyond our understanding.