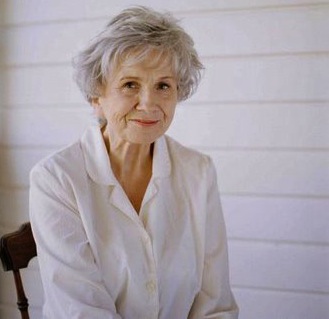

When it was announced this week that short-story specialist Alice Munro had won the Nobel Prize for literature, Canadians from coast to coast shook their heads in wonder and smiled inwardly with deep satisfaction. Canada has produced many great writers, but no other writer has such unequivocal support or is more admired than Alice Munro. She writes with modesty, with precision, with insight into human character and has the skill to evoke a powerful range of feelings with subtlety and nuance. She is truly Canada’s Chekhov.

The following quote by Munro has appeared in just about every tribute and news-story about the author: “I want to tell a story in the old-fashioned way—what happens to somebody—but I want that ‘what happens’ to be delivered with quite a bit of interruption, turnarounds, and strangeness. I want the reader to feel something is astonishing—not the ‘what happens’ but the way everything happens.”

But how exactly does Munro achieve this? I approach this question by looking at two stories about neighbors, “The Shining Houses” (from Dance of the Happy Shades, 1968) and “Fits” (from The Progress of Love, 1985). One is the story of the cruelty of supposedly good people; the other traces a town’s reaction to the murder/ suicide of an elderly couple. Both stories have an outward action and an inward action. Events trigger reactions and it is the contemplation of these reactions that awaken a new sense of understanding in the central characters.

“The Shining Houses” has a single narrator and the story revolves around her sudden awareness of the vulnerability of an individual who stands apart from the impulses of the community. In a neighborhood that is being gentrified, rapidly changing from sparse unkempt hobby-farms to densely-packed suburb with well-attended gardens and manicured lawns, one old lady who refuses to change is seen as a bothersome nuisance; her home is an eyesore to the movement of progress. A plan is put in place to evict the old lady and have her house torn down. The narrator sees the callousness of this scheme, and the uncharitable lack of sympathy for someone who represents part of the history of the place. The new neighbors act selfishly, but disguise this self-interest as community virtue. This is how Munro describes it: “And these were joined by other voices; it did not matter much what they said as long as they were full of self-assurance and anger. That was their strength, proof of their adulthood, of themselves and their seriousness. The spirit of anger rose among them, bearing up their young voices, sweeping them together as on a flood of intoxication, and they admired each other in this new behaviour as property-owners as people admire each other for being drunk.”

When the narrator refuses to go along, she realizes, as an individual acting in opposition to the group, she opens herself up to a similar kind of targeting. So why does she take the oppositional stance that she does? She is powerless to help the old lady who will be evicted. She has no influence within the group. Still there is a sense that by voicing her opposition, she has performed a small act of courage and held true to her own conscience. She may pay a price for this in the future. In fact that price has already begun as the narrator starts to separate herself from the others in her mind.

“Fits” has a more complex structure with its diverse narrators and multiple back-stories. Reactions to an unexpected and gruesome crime reveal striking differences among the characters, whose values are shaped by long-ago events. A husband thinks back on his former love affairs with married women, affairs he now regards as an avoidance of reality. Munro writes: “‘There are things I just absolutely and eternally want to forget about,’ Robert had told Peg. He talked to her about cutting his losses, abandoning old bad habits, old deceptions and self-deceptions, mistaken notions about life, and about himself. He said that he had been an emotional spendthrift, and had thrown himself into hopeless and painful entanglements as a way of avoiding anything that had normal possibilities. That was all experiment and posturing, rejection of the ordinary, decent contracts of life. So he said to her. Errors of avoidance, when he had thought he was running risks and getting intense experiences.”

Tiring of these passionate but difficult entanglements, the man marries a practical woman who shares his desire for a home and family. Unfortunately, his wife lacks imagination, as well as the ability to share her deepest feelings with others. This failing becomes glaringly clear after the wife discovers the bodies of the murdered couple. The wife informs the police but neglects to tell a single member of her own family of her horrific discovery, nor does she confide to them any sense of her reaction to this shattering event.

The way people talk and interact with one another is one of Munro’s chief concerns, the bridges and barriers created by the slightest of gestures. She sets up the differences between husband and wife like this: “His friendliness and obligingness were often emphatic, so that people might get the feeling of being buffeted from all sides. This is a manner that serves him well in Gilmore, where assurances are supposed to be repeated, and in fact much of the conversation is repetition, a sort of dance of good intentions, without surprises.” In contrast to the husband’s garrulousness is his wife’s reserve. “Peg smiled as she would smile in the store when she gave you your change–a quick transactional smile, nothing personal … Robert once told her he had never met anyone so self-contained as she was. (His women have usually been talkative, stylishly effective, though careless about some of the details, tense, lively, ‘interesting.’) Peg said she didn’t know what he meant.”

The husband contrasts his wife’s non-reaction to the crime to the over-reaction of the town’s people who can’t stop talking about the murdered couple and the possible motives for why it happened. The husband is aware of his own over-active imagination. It’s a flaw, but at least it is one he’s able to share, along with his struggle to manage it in appropriate ways. After a long winter walk, he decides to return to his wife, though he remains troubled by her cool demeaner.

The story ends with new information, information unknown to the husband. This information suggests the wife was indeed affected by the scene she witnessed. She was so affected that she lied about certain details in order to cover-up what she went through. The husband doubts his wife, but his understanding of her is incomplete and imperfect. This is where the story ends, with doubts, lies, and an imperfect understanding of the other. It is not the murder that is strange in this story; it is the way the murder leads to a maze of unexpected connections and misconnections, misgivings and unresolved needs, among the seemingly unimportant characters.

I’m tempted to link Munro to the movement of Magical Realism often associated with Gabriel García Márquez, Isabel Allende, Salmon Rushdie, and other writers who mix fantastic elements into otherwise closely observed and detailed stories. While Munro’s prose is not as saturated and flowery as these more ‘tropical’ writers—she has that Northern coolness of temperament—two key features of Magical Realism abound in her work: the multi-layered stories-within-a-story and the presence of ghosts. By ghosts I mean the sudden (often inconvenient) eruption of the past into the present and the feeling of characters being haunted by a force not known or knowable by others.

In the stories I’ve cited, the evicted woman in “The Shining Houses” serves as a kind of ghost and she affects the narrator in ways that her other neighbors will never understand. The evicted woman is the only character with a back-story, which tells of a ghost-like husband who abandoned her. Munro has her narrator uncover this fact: “She did not talk to many old people any more. Most of the people she knew had lives like her own, in which things were not sorted out yet, and it is not certain if this thing, or that, should be taken seriously. Mrs. Fullerton had no questions of this kind. How was it possible, for instance, not to take seriously the broad back of Mr. Fullerton, disappearing down the road on a summer day, not to return? ‘I didn’t know that,’ said Mary. ‘I always thought Mr. Fullerton was dead.” “He’s no more dead than I am,’ said Mrs. Fullerton, sitting up straight … ‘he’s just gone off on his travels, that’s what he is.'” The old woman refuses to move from her rundown house because otherwise how will the ghostly husband ever find her? The eviction, which she does not know is in the works, will cause a metaphysical rupture from which it is unlikely she will recover. This is the purpose of the ghost.

“Fits” draws its title from a theory advanced by the character Robert: people behave like landscapes that are prone to periodic earthquakes, eruptions, and other fits, the causes of which are largely hidden and invisible. The ghost in this story is also a husband who has deserted his wife and disappeared in search of a place that is equal to his imagination. The ghostly husband represents the need for imaginative or psychic connection with another person. Without this, one encounters the ghost state of metaphysical rupture. Robert has taken the ghostly husband’s place and sees a similar dilemma opening up before him. “A man doesn’t just drive farther and farther away in his trucks until he disappears from his wife’s view. Not even if he has always dreamed of the Arctic. Things happen before he goes. Marriage knots aren’t going to slip apart painlessly, with the pull of distance. There’s got to be some wrenching and slashing.” Fits of strangeness reveal the truth that any life contains its fair share of secrets and scars that can never be entirely erased, as well as images and emotions that cannot be communicated adequately from one person to another.

I’d like to thank my sister Janet Pope for suggesting the topic of this post and for lending me copies of the two stories by Alice Munro. Along with the books, Janet wrote me the following note to add to this blog:

“Like an archaeologist assigned an unpromising site, Alice Munro takes ordinary people and starts digging through layers, accumulations, detritus of the past till she uncovers evidence of a richly imagined life. This patient exploration in story after story changes the reader. She enlarges the assumptions we had about others which are usually narrow and static. She makes us see that people are endlessly complex, ‘moving out of their prisons, showing powers we never dream they have.’ Through the Munro process, we, as ‘ordinary people,’ learn to recognize and respect our subterranean depths.”