Advertising is the great evil, the great annoyance, the less-than-truthful spin of which everyone despairs. Yet adversing may serve as the very foundation of modern media as revenue from ads finance our newspapers, radio, television, Internet and social media. In this blog, I look at 5 theories applied to advertising and consider how the different approaches intersect.

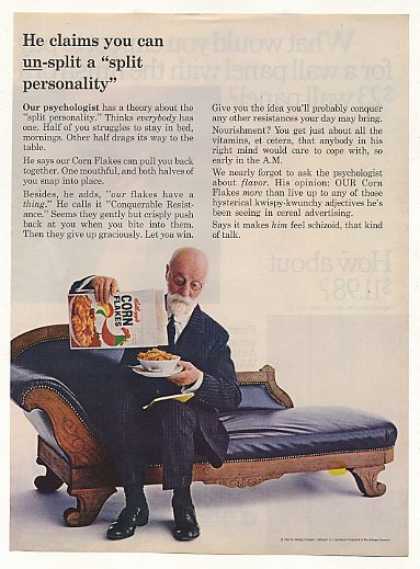

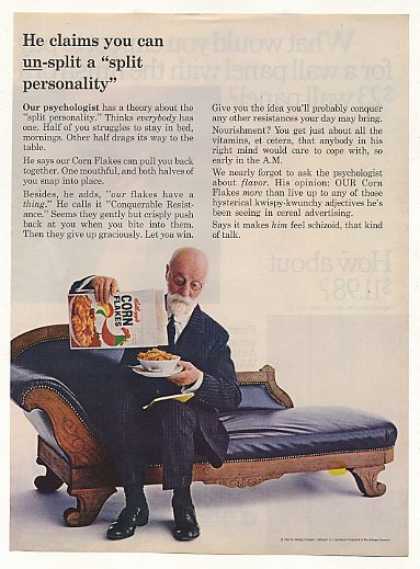

Kellogg’s Corn Flakes Psychologist Personality (1967)

1. The hidden message. The idea that ads mislead and unconsciously manipulate the viewer was advanced by sociologist Vance Packard in his 1957 best-seller, The Hidden Persuaders. Packard argued that advertising is dangerous because it uses psychology to create emotionally-loaded hidden messages. Because the message is hidden, the viewer’s critical resistance is evaded and minimized.

The Cornflakes ad at left suggests this product promotes not just good physical health, but also good mental health. It is a classic instance of “a doctor uses this product, it must be healthy” approach. It also demonstrates how psycho-analysis has entered the mainstream and become something of a joke. The joke is that we are all split personalities, wavering between lazy hedonism and disciplined self-improvement. Happily, cornflakes serve both interests: they are a candy-like treat and they are also a form of breakfast.

2. Shifting loyalties. Ads play upon and reflect conflicted, ever-changing loyalties. While ads try to cultivate a strong sense of brand loyalty, ads also urge consumers to change loyalties, to try something new, to disavow an old loyalty in favour of a new product.

In her study, Advertising in the 60s, (Praeger, 2001), media historian Hazel W. Warlaumont argues that ads changed from the 1950s to the 60s. The look and message of many ads appeared to embrace the anti-authoritarian hippie counter-culture, all the while being designed and distributed by giant corporations promoting the status quo and capitalist interests. Warlaumont argues that advertisers co-opted the anti-establishment’s “ideals, leaders, icons and goals into the existing structure.” (p. 138)

Not only does the revolutionary socialist Che Guevara appear on T-shirts, but the commercial success of this icon leads to imitations and parodies such as the Cher Guevara shirt on right.

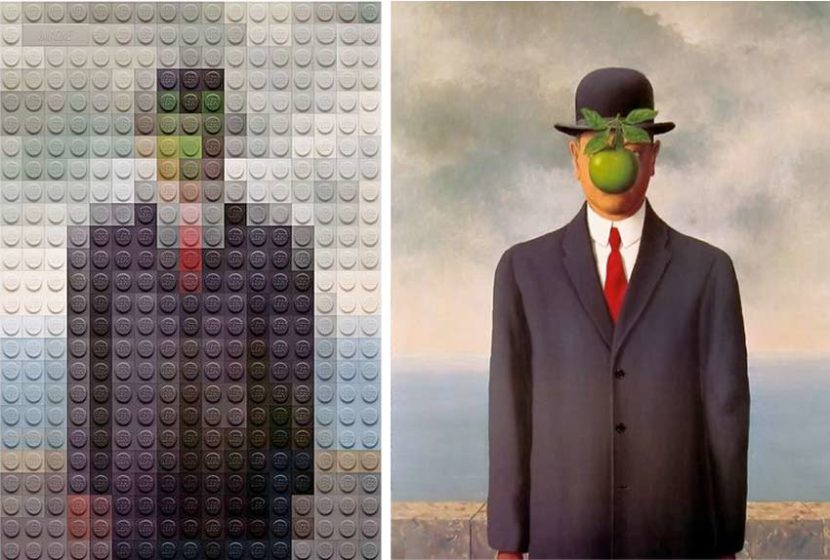

Warlaumont’s argument inverts the concept of détournement, developed by activist Guy Debord and others in the 1960s. Debord was leader of the radical collective, Situationist International and author of The Society of the Spectacle, 1967. Détournement refers to an artist’s reuse of familiar images, by shifting contexts to create a new work with a different often contrary message. Détournement has an element of ‘anti-art’ using blatant theft and sabotage of existing elements, turning the original message against itself. The idea leads to the later strategy of culture jamming. Both strategies are conceived as a method of resistance to the grosser elements of Capitalist culture and raise awareness of corporate ploys and their social effects.

An example of an ad using elements of détournement is the print ad below sponsored by the World Wildlife Federation. The “turned” element here is the portrayal of a toxic industrial can as both a kind of giant urban monument and as the polluted life water of the city. The image redirects the pride we might take in the magnitude of our industrial complexes into a fear that we are poisoning the very environments that are essential to our existence.

wwf.Advertising AgencyContrapunto, Madrid.2007

The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, 1968 animated film by Canadian animator George Dunning.

Changing the intent of public messages is a two-way street however, practiced by advertisers just as readily as by activists and artists. Détournement gives way to recuperation. Originally subversive works and ideas are themselves appropriated by mainstream media. The philosopher Gilles Deleuze speaks of deterritorialization and reterritorialization to describe this ongoing war of counter-ideologies.

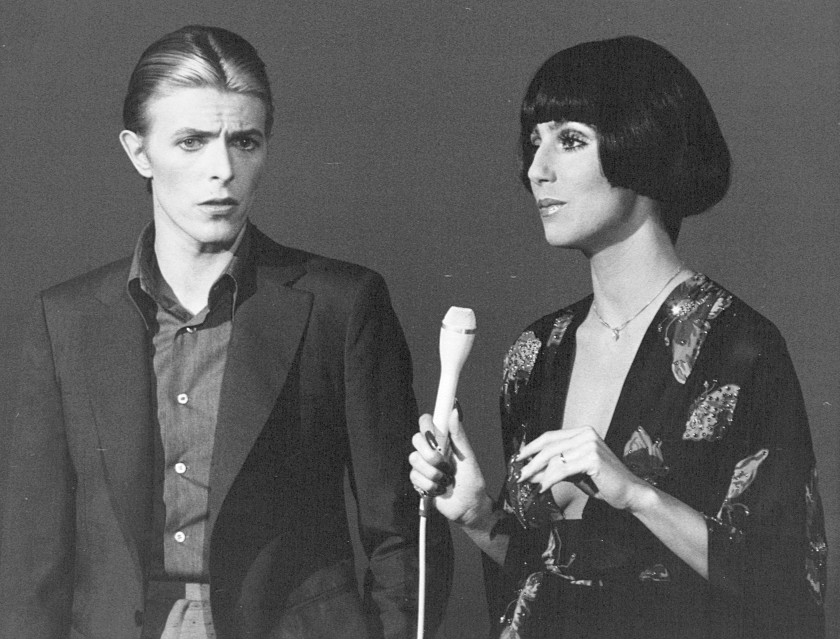

These image wars reflect shifts in loyalties and conflicted loyalties. For instance, the Beatles were leaders of the 60s counterculture, with their experiments with drugs, their personal song lyrics, anti-war attitudes and openness to Eastern philosophy and religion. However the Beatles also invented the music video and pioneered the use of cross-branding music, films and related products, as the ad above demonstrates.

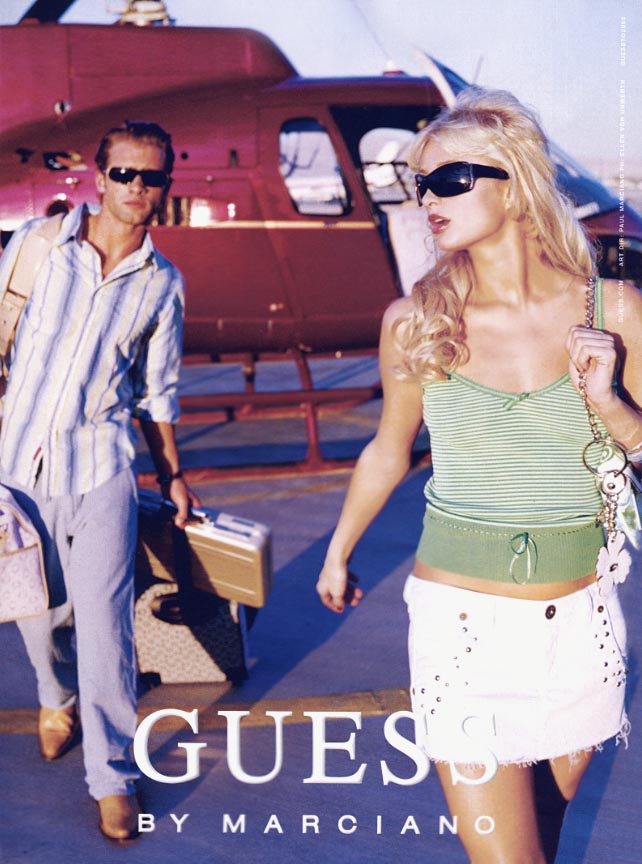

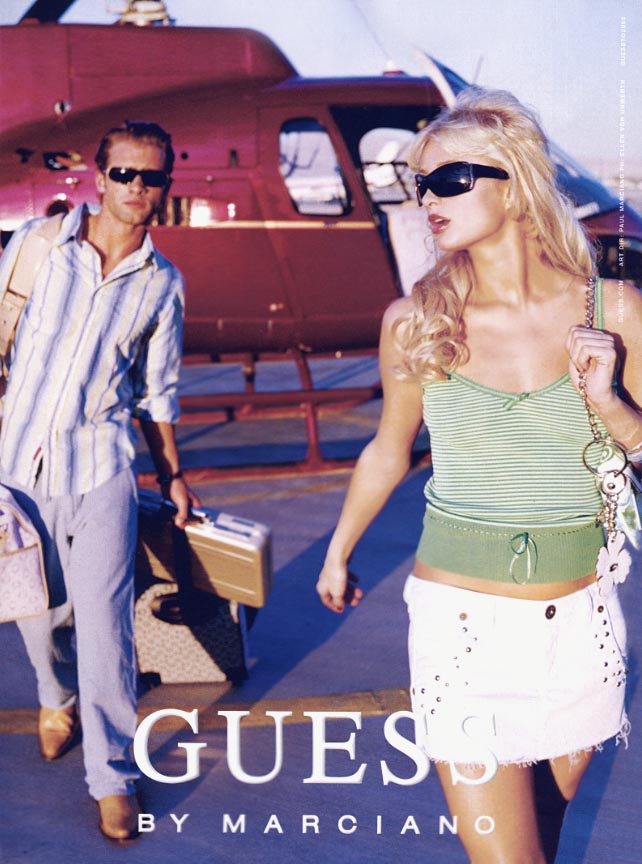

Playing on her own image, Paris Hilton features in a series of Guess ads in 2009

3. The mediation of reality. Ads only work in conjunction with other media and environments in which they are embedded and cannot be understood apart from other media and environemnts. Marshal McLuhan noted that it is not the content of ads that makes them so persuasive. Rather it is the way they use media to fuse together a world of actions and a world of fictions. McLuhan writes: “When the movies came, the entire pattern of American life went on the screen as a non-stop ad. Whatever any actor or actress wore or used or ate was such an ad as had never been dreamed of … The result was that all ads in magazines and the press had to look like scenes from movies.” (Understanding Media, 1964, p. 252) InThe Image: A Guide to Pseudo-events in America, 1962, historian Daniel J. Boorstin describes how news and advertising have blended together to such an extent in popular media that they create an impression in which truthful reporting becomes ambiguous and the difference between a serious newsworthy event and a fabricated news event, such as a publicity stunt, is indistinguishable. But Boorstin does more than just describe how ads disguise themselves as news. He sketches the origins of celebrity culture, as fame and overblown public exposure become coveted ideals not just among a small set of people but among the general population of image and media consumers. However the ability to generate publicity and controversy, to saturate and bombard, to get people noticing, talking, arguing is something products do as well as people. We have celebrity brands. Advertising thrives in a celebrity culture and is integral part of it.

In the ad for Guess shown above, Paris Hilton steps off a helicopter accompanied by a male lover/ servant rolled into one. She exudes an air of wealth and glamour, playing her private life out in the public eye as heiress, model and reality TV star. The ad looks like a paparazzi photo, blurring boundaries between reality and fantasy.

McLuhan explains our addiction to media by pointing out that media extends and heightens sensory responses. For example, why do we like to read press stories of events we’ve already witnessed? McLuhan answers: “The press repeats the excitement we have in using our wits, and by using our wits we can translate the outer world into the fabric of our own beings. This excitement of translation explains why people quite naturally wish to use their senses all the time. Those external extensions of sense and faculty that we call media we use as constantly as we do our eyes and ears, and from the same motives. On the other hand, the book-oriented man considers the non-stop use of media debased; it is unfamiliar to him in the book-world.” (p. 229) Media adds an extra level of mediated experience to things we already know, giving to reality a sense of hyper-reality. Ads thrive in this land of extra-mediated hyper-reality.

Rock stars save the planet in this Louis Vuitton ad, 2010, photo by Annie Leibovitz.

4. The magic of meaning. Ads don’t just sell products but infuse those products with meaning for the people who use them. In this way, ads influence our values and underlying beliefs. Carlyle put it rather bluntly in the 19th century: “The quack has become God.” In his seminal essay, ‘The Magic System‘ (1962), cultural theorist Raymong Williams argues that advertising “has passed the frontier of the selling of goods and services and has become involved with the teaching of social and personal values; it is also rapidly entering the world of politics. Advertising is also, in a sense, the official art of modern capitalist society: it is what ‘we’ put up in ‘our’ streets … and it commands the services of perhaps the largest organized body of writers and artists, with their attendant managers and advisers, in the whole society.” Williams goes on to remark that as a form of organized magic, advertising obscures the true nature of consumerism and its effects on public attitudes and social goals. Keeping the public away from discontented questions, advertising “is a true part of the culture of a confused society.”

The above ad uses many of the same features as the Paris Hilton ad for Guess, but the message is the opposite. The party girl in the helicopter was looking for adventure and excitement, indulging her own whims and revelling in the exposure and notoriety this indulgence brings to her. In the above ad, the celebrity rock star Bono and his wife Ali Hewson descend from the sky like angels into a pristine African wilderness, which their activities will be protecting. Bono uses corporate sponsor Louis Vuitton, working together with his own company Edun, to produce hand-bags made in Africa. Proceeds from sales are reinvested in the local economy. The ad functions as a fundraiser, but also suggests Bono and wife have come to Africa for other reasons. Returning to the roots of humankind for inspiration, it is the ultimate trip. The ad plays on ideas of youth, travel and self-discovery, mixed in with an altruistic concern for other people and other places.

James Twitchell, author of Adcult USA: The Triumph of Advertising in American Culture, 1996, writes: “Mid-twentieth-century American culture is often criticized for being too materialistic…we are not too materialistic. We are not materialistic enough. If we craved objects and knew what they meant, there would be no need to add meaning through advertising … What is clear is that most things in and of themselves do not mean enough. In fact, what we crave may not be objects at all but their meaning. For whatever else advertising does, one thing is certain: by adding value to material, by adding meaning to objects, by branding things, advertising performs a role historically associated with religion.” (p. 12)

The essential message of all ads.

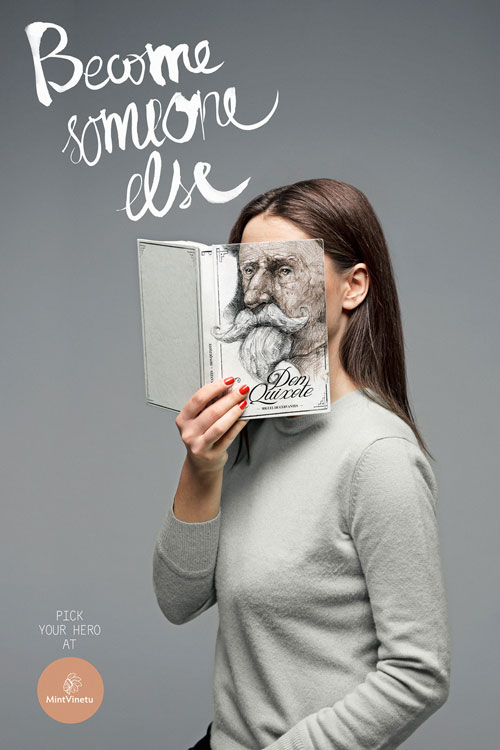

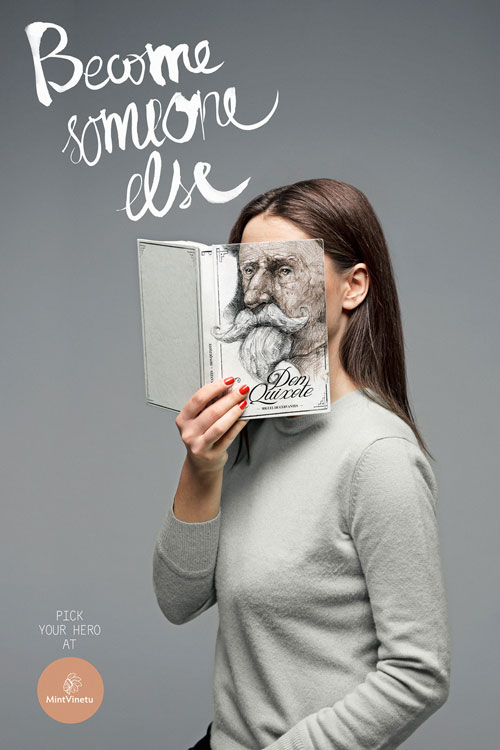

5. Imitative desire. Ads play upon people’s tendency to desire what others desire. French theorist René Girard argued that we often desire to become the other (when the other is powerful, famous or beautiful). However it is impossible to become another person. This impossibility keeps our desire alive. Girard’s ideas are explained in depth in Kathleen M. Vandenberg’s

“Sociological Propaganda”. Vandenberg argues that ads function as interactive rituals rather than as one-way messages. The essence of a ritual is that people place themselves in communities through imaginative projection toward others.

The ad for a bookstore above, suggests that books function as escapes from ourselves as we take on the disguises of others, stepping into imaginary worlds. Ads serve a similar function. We see a product. Someone in the ad wants the product. We want the product because it is desired by others. This is René Girard’s idea that our desires are always mediated. Ads cannot affect us unless we participate in the social ritual, the imitative act, that they invite us to.

Conclusion

I have outlined 5 ideas concerning advertising. It is remarkable how these ideas appeared within ten years of one another, the span from sociologist Vince Packard’s The Hidden Persuaders in 1957 to Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, 1967. Each viewpoint acknowledges that ads reflect, but also distort certain aspects of our lives. Commentators such as Packard and Barthes argue that ads need to be critiqued to reveal hidden messages, hidden ideologies. Raymond Williams suggests that ads are an effective form of propaganda because they play on our patterns of social bonding and our loyalty to symbols. Winning this loyalty involves the shaping of opinions and beliefs. Kathleen M. Vandenberg notes how advertising “exhibits many of the characteristics of propaganda; chief among these characteristics is a speaker’s reliance on self-interest (rather than the good of the audience), anonymity (or the suppression of ethos), the use of saturation or repetition of messages (rather than the delivery of formal speeches), and the employment of emotional appeals (rather than logical ones). Advertising meets these criteria insofar as it is, in the words of Twitchell, “ubiquitous, anonymous, syncretic, symbiotic, profane, and, especially, magical.”

Historian Daniel Boorstin, author of The Image: A Guide to the Pseudo-event in America, 1962, suggests that the critique of ads leads to controversy, the key ingredient of celebrity culture. Critique does nothing to demystify a product, rather just the opposite. Debord suggests that in an ideological war all the rules of rational debate go out the window. If you want to oppose the message of an ad or the corporate aims which it promotes, then you must counter-attack, manipulating language, image and context to turn the message against itself. McLuhan’s approach to ads is to consider them an inseparable part of media and mass communication, part of an on-going technological revolution. Like every other message, ads obey the four laws of media. Applying McLuhan’s laws to ads, one could say: ads enhance our senses, ads make other types of messages obsolete, ads retrieve overlooked areas of culture from the past, ads lead to unexpected side effects which trigger reversals opposing the original initiative. Turning from technology to religion, Girard suggests we should not speak of reforming ads, as much as of reforming ourselves. Humans are great imitators and mimics, in need of a sense of belonging and a sense of meaning. But when we try to fill our deepest needs by imitation alone, we get in trouble.

I personally believe that all of the above positions have merit. The purpose of a critique is not to combat evils, but to enhance understanding and clarify values, to lessen the distance between what we’re doing and what we’d like to do. For those who prefer taking more direct actions, Debord’s strategy of détournement may be more useful. It recognizes advertising is an infinitely adaptable tool that can serve the revolution as well as the corporation. McLuhan helpfully reminds us not to focus exclusively on messages, but to also study the media and environments in which messages are conveyed. We need to keep reinventing media and reconfiguring our social networks. McLuhan believed electronic and digital media were making culture more participatory and interactive. However the more we interact, the more we tend to imitate others. This is why I conclude on Girard’s notion that we need to take responsibility for our acts of imitation.