The Audain Museum in Whistler is itself a work of art. Designed by John Patkau Architects, the L-shaped building stands on stilts. It’s entered by a bridge that floats above a garden.

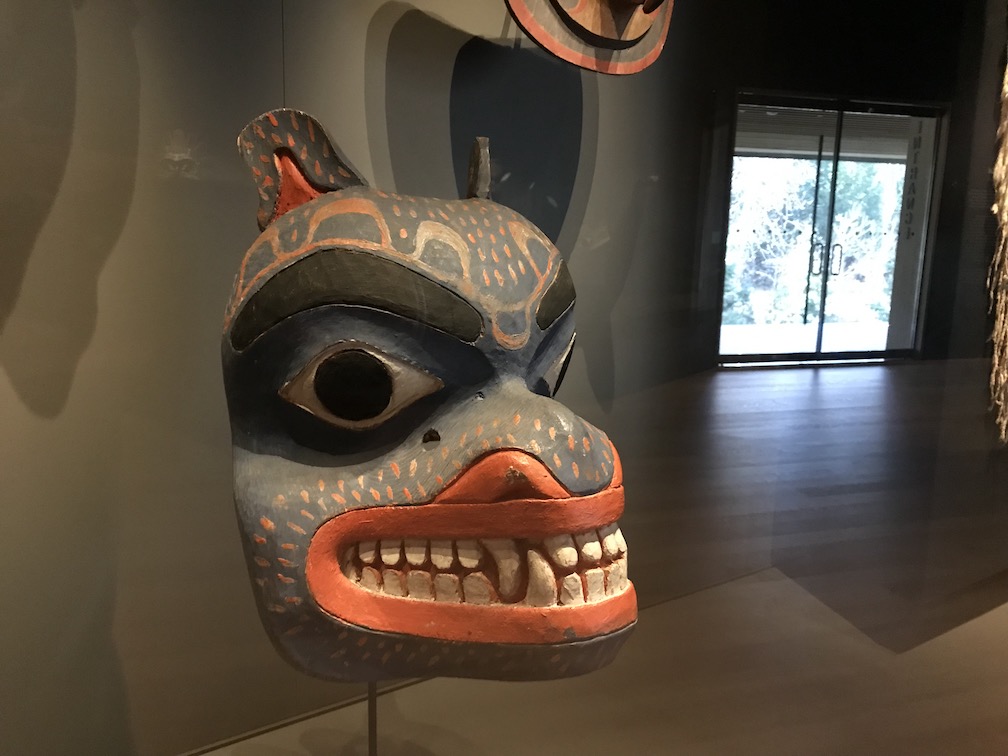

A long sun-drenched corridor links the entrance to the exhibit halls. All art inside is by artists from British Columbia, starting with traditional native artists and moving to contemporary native artists, photographers with billboard-sized images, generation of the group of seven and younger artists. All the big names are here: Bill Reid, Robert Davidson, Emily Carr, Jeff Wall, Brian Jungen.

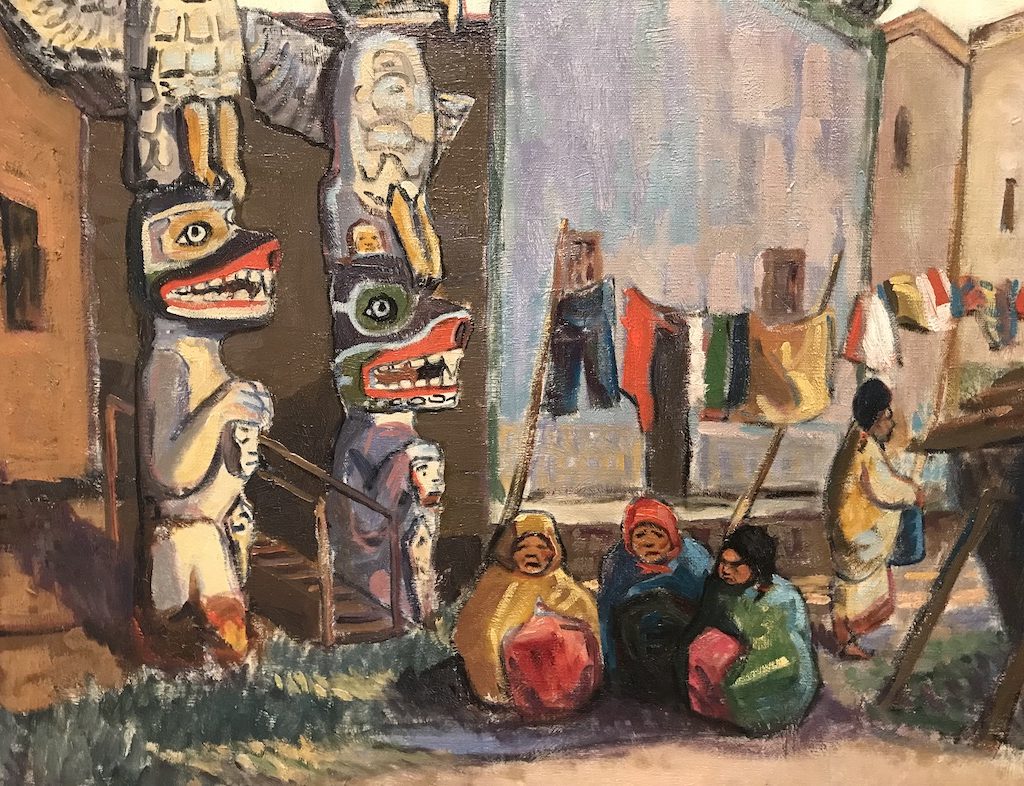

When I’m in art galleries I like to take pictures of details. For instance I like how the crowded spiky seeds on the chestnut tree contrast with the delicate half-finished flowers and outstretched artist’s hand in the Lukacs image and the clothesline in the Emily Carr next to the red-mouthed totems.

Emily Carr painted this native village in 1912, one year after her 16 month study tour of France, where she was exposed to experiments in modern art. Emily’s style is fresh and assured, using broad strokes, bright colours and strong well-defined forms to depict these time capsules of village life. In the image above, she uses repeating totem poles to add rhythm and vertical thrust to the receding street. The dramatic presence and animal vitality of the totem poles capture our attention. Yet what’s most striking is how the poles are so intimately situated in the midst of houses, children and clotheslines.

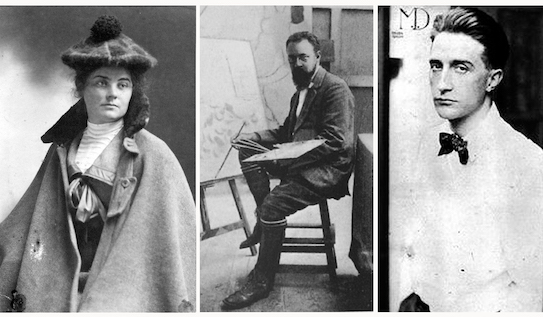

together at the Salon d’Automne in Paris, 1911.

An interesting side note to the Carr exhibition: while in France, Emily exhibited her work alongside the paintings of Henri Matisse and Marcel Duchamp in the Salon d’Automne, Paris. She was a daring young artist stretching her wings at the exact moment that they were also testing the limits of their craft–young lions together!

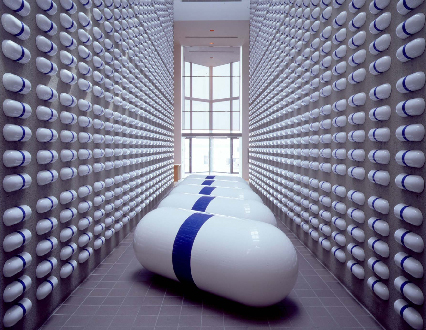

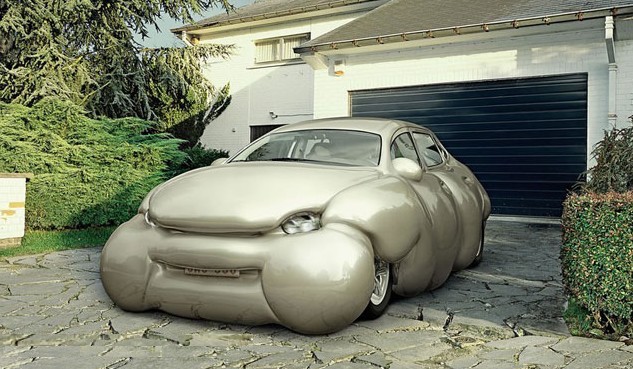

I wish I’d had time to take pictures of cars and street signs, but I had less than a day in the city. When I heard there was an off-site work by Austrian sculptor Erwin Wurm, I thought immediately of his fat car series.

Wurm’s one minute sculptures, where he asks people to balance an awkward pile of stuff–it’s impossible to hold the pose for longer than a minute–are also interesting. I was eager to learn what he had in store for Vancouver. Here’s his off-site work: two empty suits dancing.

I started this blog with masks so I’ll end with masks.

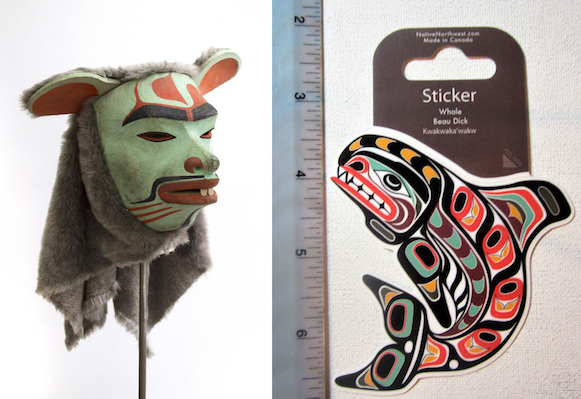

All artists balance tradition and revolt, political and personal, and this tension is evident in these unusual and challenging works.

In the work above, the garbage bag becomes a temporary mask obscuring the mask inside. It makes me think how objects and relationships of great value to some are too quickly discarded by others. In a review (Canadian Art, May 2019) of Beau Dick’s New York exhibit, Devoured by Consumerism, Julian Brave NoiseCat writes: “One of Dick’s last works, produced in 2016, was the carved yellow cedar Towkwit Head, wrapped in a black garbage bag, with a painted eye and horsehair brow peeking out from a hole in its crude cover. Towkwit is a feminine spirit who cannot be killed. In ceremony, a Kwakwaka’wakw spiritual leader cuts off her head, sets her on fire, resurrects her and repeats the process over and over again.”

“Our whole culture has been shattered,” says Dick in the documentary film, Maker of Monsters. “It’s up to the artists now to pick up the pieces and try and put them together, back where they belong. Yeah, it does become political. It becomes beyond political; it becomes very deep and emotional.”

It may be insensitive to say this, but I feel the same way as Beau Dick, my culture has been shattered also. To illustrate what I mean, here are pictures from three museums visits.