The Group of Seven are well known in Canada, but ask any one to name an individual artist within this group and chances are you’ll draw a blank. Ironically, the two artists that most readily come to mind, Tom Thomson and Emily Carr, were not members of the Group, though close friends with those who were. Thomson was murdered before the group was officially formed and Carr was never invited to join.

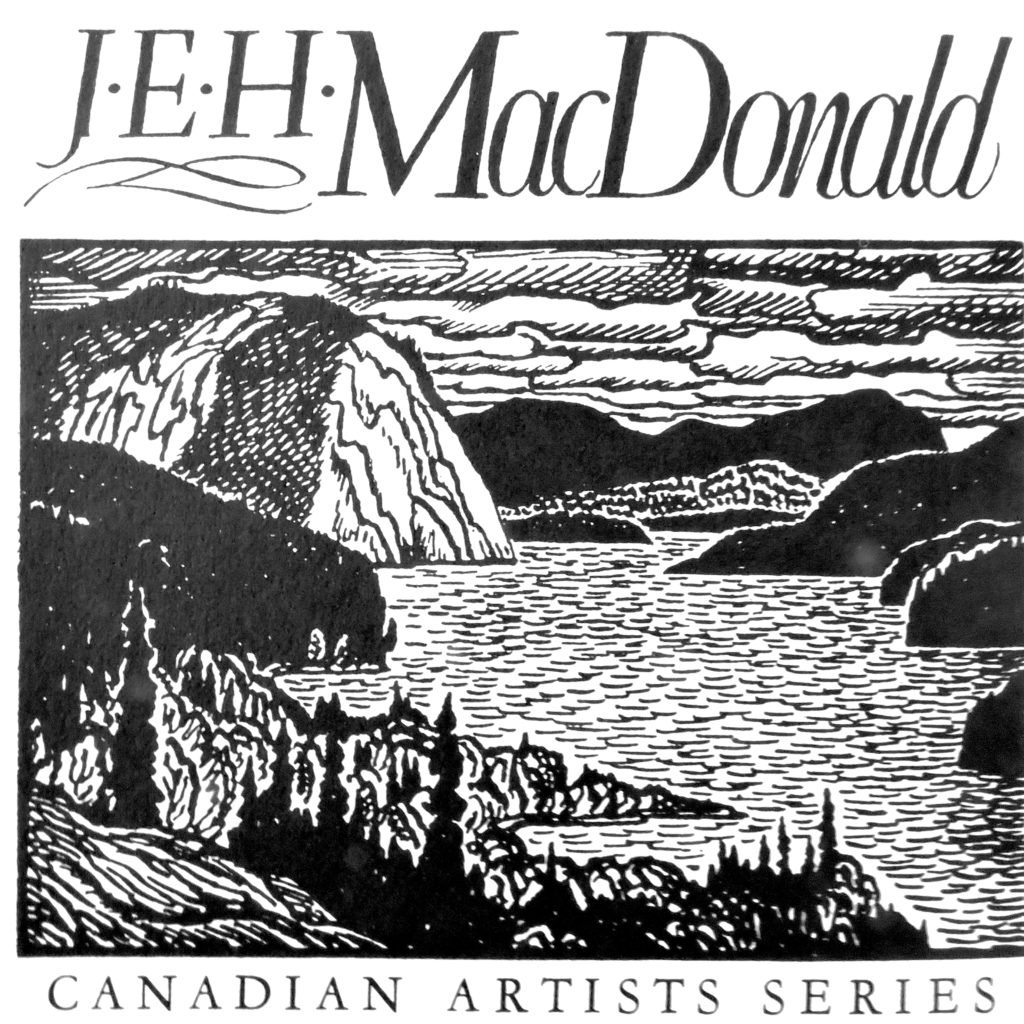

This blog is about overlooked talents. The person I’d like to feature is Thoreau Macdonald, named after the famous 19th century naturalist, Henry David Thoreau. Macdonald’s father was J.E.H. Macdonald, one of the original Group of Seven, a landscape painter noted for his dazzling colour. Incredibly his son Thoreau was color blind. He compensated for this by working exclusively in black and white as a book and magazine illustrator. TM (Thoreau Macdonald) often worked on catalogues promoting other artists for which he created punchy graphic images. These black and whites often mimic the style of the featured artist.

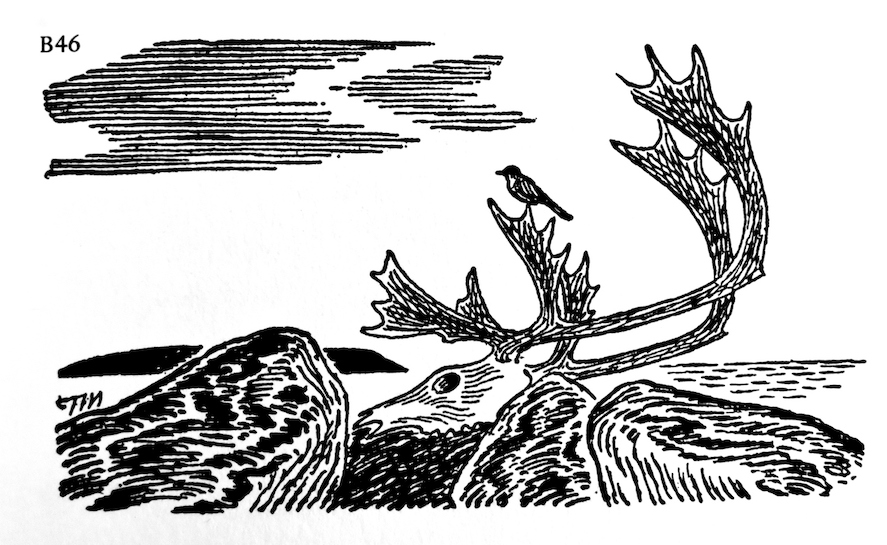

My wife just asked me, are these images woodblock prints? No, they’re done in pen and ink to look like woodblocks–they are “fake woodblocks.” TM eschews the intricate cross hatching that gives many illustrations a range of tones and a heightened sense of realism. Extreme contrasts, varied mark-making techniques and beautiful designs contribute to TM’s unique style.

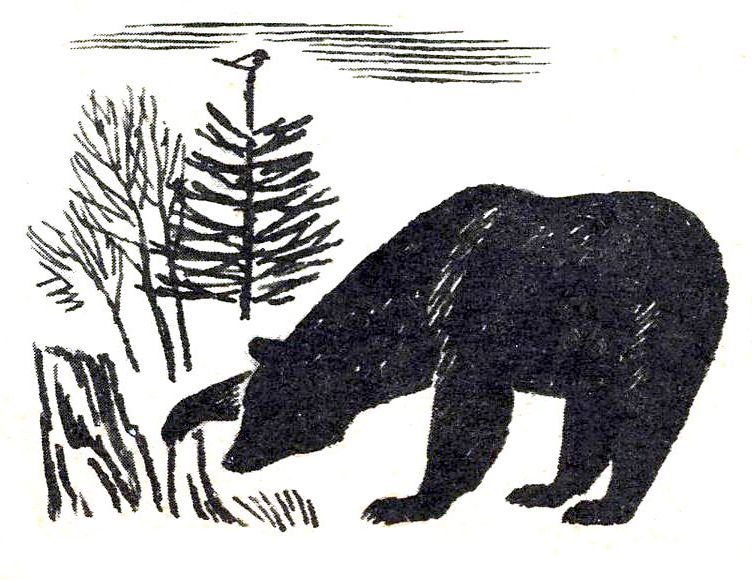

Birds and animals are often included in these landscapes. TM is one of the first Canadian artists to do this and, in this respect, he anticipates Robert Bateman and Alex Colville. TM’s animals are not symbols or decorative abstractions, but embody a life presence of their own. These curious explorers actively interact with other species in an ecological time capsule. There is a strong sense of season and locale. In the picture below, it’s spring time; the hungry bear has awoken from a long sleep. He uses his great strength to tear apart a tree stump as he searches for grubs. A vigilant bird hovers in the background, awaiting his chance to swoop in and clean up the left-overs. The image contrasts the hugeness of the bear with the smallness of the bird and the low dead stump with the springy young trees beyond. There are visible creatures (bear and bird) and invisible but implied creatures (the grubs). No distinction between land and sky: a white day.

How beautifully the arch of the tree branch frames the fox, giving the sense that he is earthbound, while the birds, so much on his mind, are safely out of reach. How effective is the white of the page as a field of snow! The snow half hides the old tree in the aftermath of a storm. Life is just beginning to emerge and take a peek around for signs of other life.

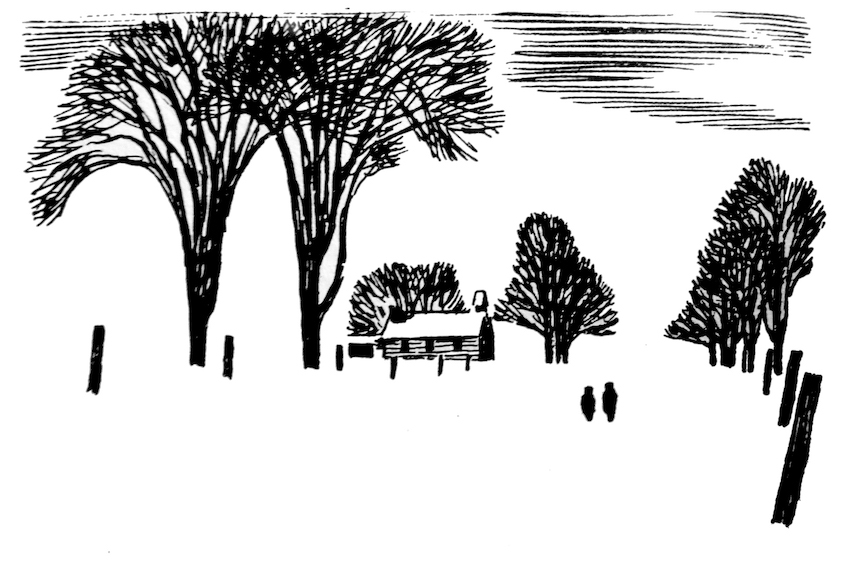

Here is another deceptively simple display of whiteness. The image is so bright it almost hurts your eyes! There is a principle in Asian art that there should be a balance between what’s drawn on the page and what’s left empty on the page. TM is a wizard of knowing what not to draw. What’s more, his empty space gives a tangible sense of distance. Fence posts and trees, drawn in perspective, act as a giant funnel guiding the figures home.

Here’s a cycle of life, cycle of seasons. Reminds me of Ozymandias. The heroic and the humble. Stones, skull and island are shapes that echo one another–looks like the caribou is turning to stone before our eyes as the rocks crowd in on the remains of the fallen animal. The horns function like the branches of a tree, a convenient perch for a bird positioned midway between the arrowhead in the cloud and the nervous current to the water. As in many of Thoreau’s images, the bird stands and watches. He is a sentient being in a wild setting, a silent witness to nature’s changes.