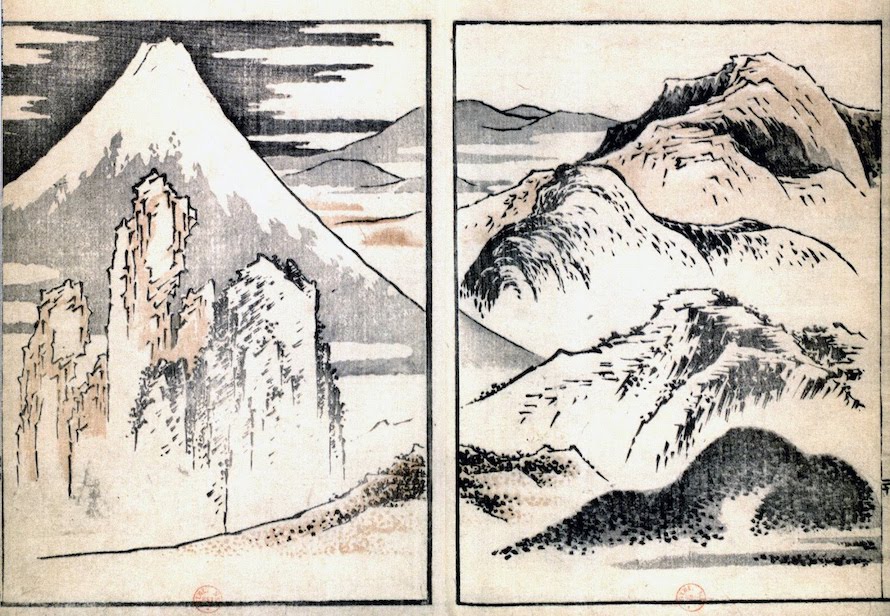

Katsushika Hokusai, Japan’s greatest artist, was born in 1760. This was the year Suzuki Harunobu introduced the “brocade print,” multi-coloured woodblock printing, setting off a boom of high-quality mass produced ukiyo-e. Hokusai apprenticed at a lucky intersection of new craft, receptive audience, and high standards among competing artists. The capital Edo, with its million inhabitants, was the world’s largest city. Townfolk and visitors sought out images of famous actors, sumo wrestlers and courtesans. Hokusai introduced two new subjects: books of manga–quick sketches of all manner of subjects, often humorous, caught unawares in daily tasks– and landscapes.

Hokusai’s manga may have served as drawing manuals for student artists, but they are as entertaining as instructive. Take the example above. Ghosts interact with a musician and salesman. The salesman hopes to sell a pair of glasses with three lenses to the spectre with three eyes. The long-necked beings waft through the air like smoke from their pipes.

Hokusai worked in the Edo period, which lasted from 1603 to 1868. This was a time of stability and prosperity for Japan. The ruling shogun introduced a unique bit of nation building–foreigners were not admitted into Japan and Japanese were not allowed to travel abroad. With their new wealth and free time, people looked to travel within Japan, taking advantage of improved roads and increased safety. Travel books were popular, none more so than Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1832, begun when the artist was 71 years old.

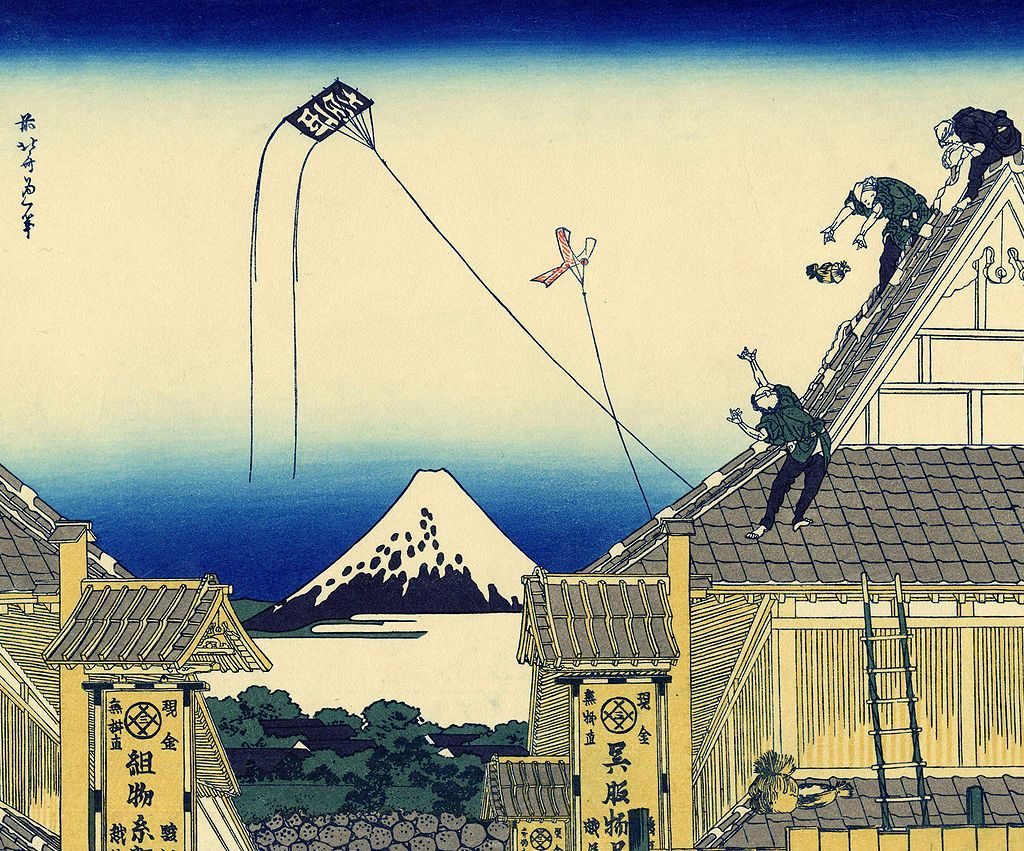

How is a kite like a mountain?

The string of the kite echoes the shape of the mountain’s slope, as do the cluster of city rooftops. But how ephemeral a bending string in the wind is compared to a centuries old mountain! In the foreground, a worker repairing the roof of a fashionable clothing store tosses a bundle of tiles to his companion.

Here is another string that mimics the mountain emerging from the mist. Hokusai is famous for his ingenuity in evoking the motion of waves. He is no less experimental in his concern for sky, cloud and mist effects and how they change with altitude and time of day.

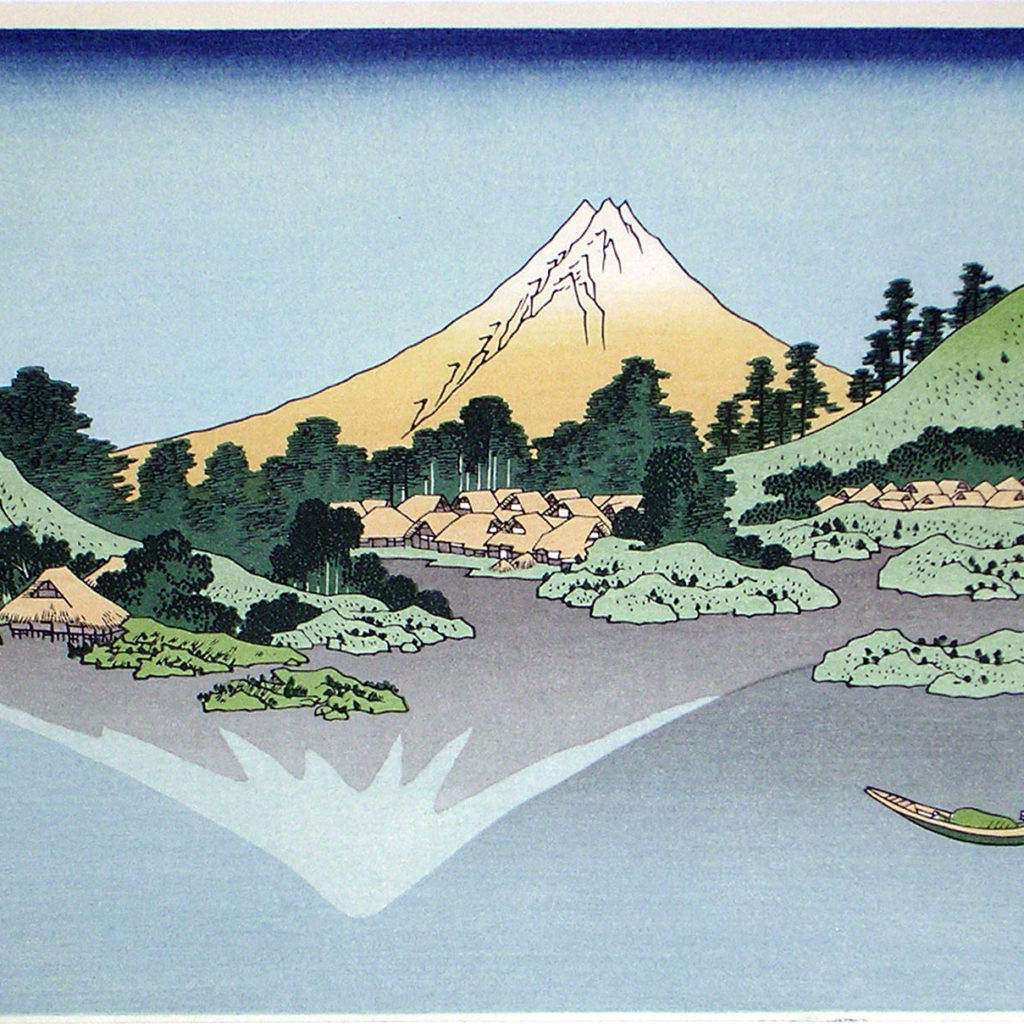

How does this mountain differ from its reflection in the lake?

The mountain is imperfect with its competing peaks and jagged crumbling surface. It’s a dull brown in the summer light. The reflection has a single resplendent peak, the winter’s snow hides all rough edges.

Hokusai’s father was a mirror craftsman, a trade to which Hokusai was exposed at an early age, before chosing art and print-making. Reflections and optical effects often find their way into his images.

What time of day is this?

The mountain glows with first light of morning, as the peak ascends through an opening in the clouds. The design is daring and kinetic: the asymmetry of the slope and mass of its red-hot body balanced by the scuttling motion of the blue-tinged clouds.

Imitation is the sincerest form of robbery. This modern take by Seattle- based artist Yumiko Kayukawa uses creatures from the natural world to suggest an unnatural world of hyper-reality. The appealing design returns ukiyo-e to its origins in pop culture.

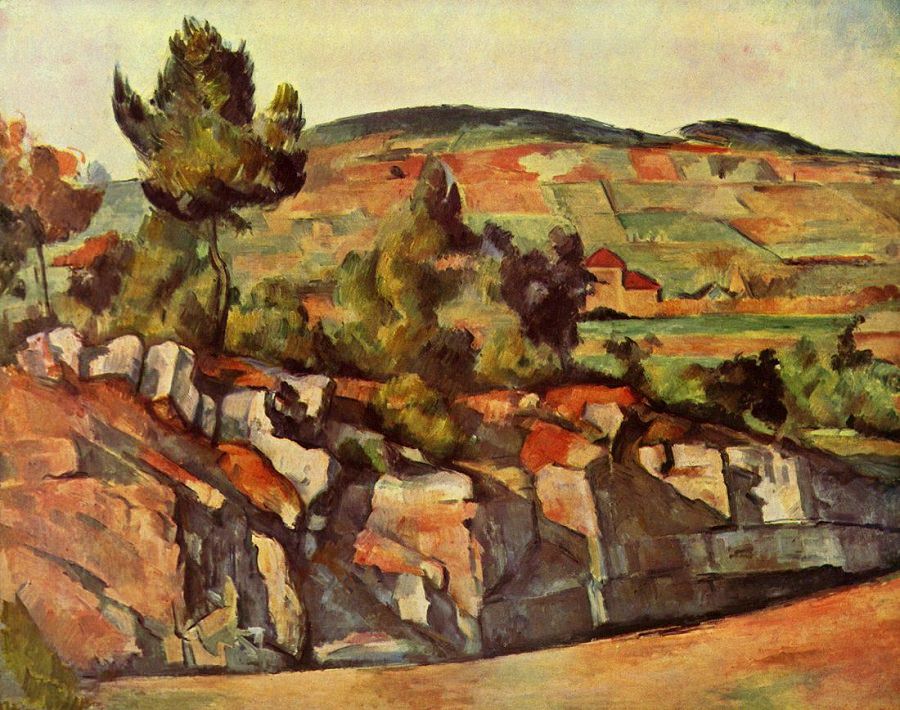

French Impressionists loved Hokusai. They copied his subjects and flat colours. They may also have been influenced by his working methods, that is, painting a favourite landmark or object over and over in a series of clever variations. Monet painted cathedrals, haystacks and his garden pond in just this obsessive way. The post-impressionist Paul Cezanne, like Hokusai, choose a mountain as his central subject. In Cezanne’s case, it was Mont Sainte-Victoire, which he depicted a total of 87 times (44 oil paintings, 43 water colours). In a letter to his friend Solari (from Talloires, 23 July 1896), Cezanne wrote: “For a long time I have remained without power, without knowing how to paint the Sainte-Victoire, because I imagined a static shadow, like others who do not look, while, look, the shadow moves, it flees from its centre. Instead of being compressed, it evaporates, becomes fluid, and participates in the air’s breathing.”