Street photography pioneer André Kertész (1894-1985) brings a poetic surrealism to everyday activities. My discussion of three photographs in which water appears in Kertész’s work is Part 2 of a series on treatments of water in art. (Part 1 here)

The Underwater Swimmer shows water as a source of recreation. It is integral to good health, self-renewal, an image of rebirth. We are not shown the edges or confines of the pool: it is a microcosm, a mini-universe. The man adapts so perfectly to these conditions that he seems almost amphibious. The water both reflects light and is a medium through which light travels. Both of these properties elicit a sense of wonder and surprise in the viewer and add to the magic quality of the image. The water produces playful patterns, while the thrown shadow makes the figure appear to soar above the bottom of the pool.

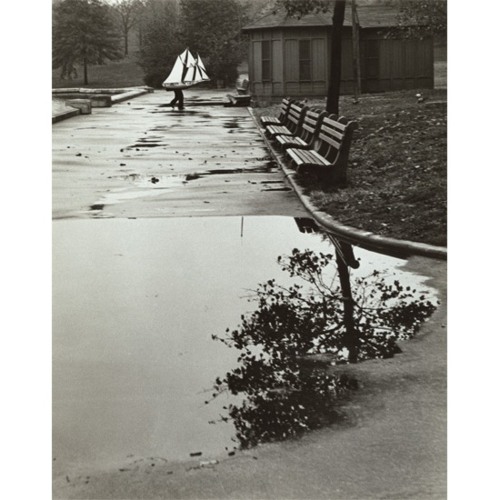

Moving from Budapest to New York via Paris, Kertész, a Jewish refugee, turned his back on the horrors of the Second World War, though the image of a sailboat on the run does hint at his own precarious immigrant status at this time. A puddle in a city street or cobbled square produces momentary mirror-like effects of a fantastic upside-down world through which characters pass as in a dream. Part of this dream quality comes from the fact that the characters themselves are unaware of how dream-like their world is. The boat that runs away from a vanishing pool of water seems to affirm reality is stranger than fiction.

Kertész had trouble selling photographs in America. Editors told him his compositions were too complex, often with the key action of the picture happening in the distance rather than in the foreground. (Pierre Borhan, André Kertész: His Life and Work, 1994, pp. 24-28) But this deep-focused multi-planed world is precisely what makes the images so charming and so charged with irony, as one character is oblivious to a telling aspect–the signs and symbols–of the city around them.

It is highly characteristic of Kertész that he uses a puddle as his source of water imagery. What could be more transitory, more humble, more ignored, even scorned than a puddle in the street! Yet these fortuitous pools help the photographer transform an ordinary street scene into a scene from a dream.

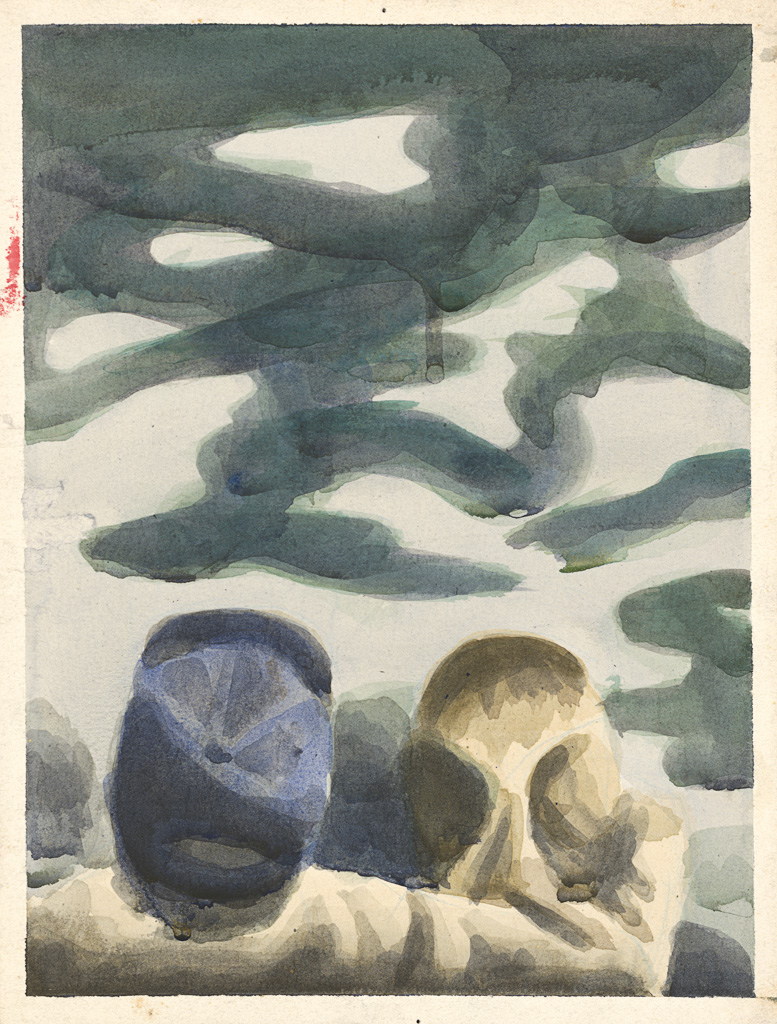

In this hillside parade of teetering umbrellas, Kertész uses a high angle view to create a humorous effect. The pedestrians, diminutive and anonymous underneath their bulky shields, appear to be corralled and herded by the signs and signals of the urban environment. Water is an important part of this environment. Though invisible in the photo, water conditions this absurd behaviour. Kertész encourages us to laugh at ourselves, but there is no shame or superiority in this laughter. Rather there is a sense of empathy and understanding, delight and transformation.

Kertész skillfully exploits the properties of water–luminance, reflectivity, mutability, invisibility–to add poetry to mundane situations. In his image of the swimmer, he shows water as a source of health and renewal. In his picture of the sailboat on the run, he shows water as a transient and vanishing substance whose presence should not be taken for granted. In the picture of the umbrellas following an arrow, he shows water as an invisible part of life to which we make necessary adaptations. In all, water is an important element of this photographic dream diary of the 20th century played out on the streets of its greatest cities.