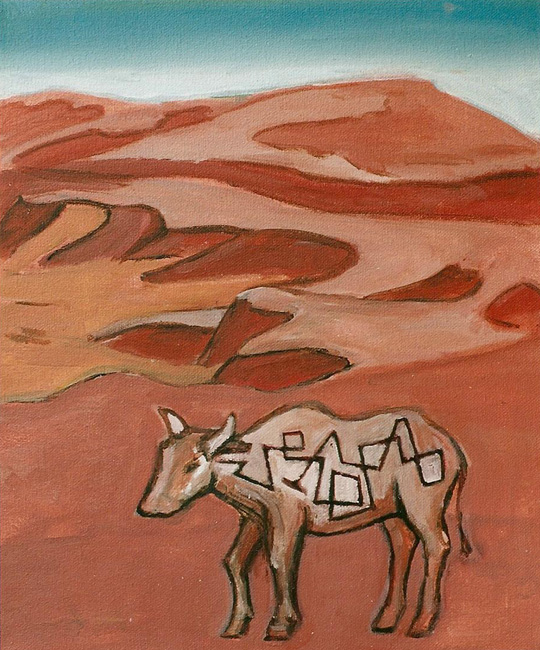

In 2002, I did a small painting of a cow in the desert, with strange markings added to the side of the animal. The markings, with their hard angles and abrupt turns, contrast with the soft undulating dunes beyond. Has this animal been branded by an over-zealous owner–or tagged by a mad graffiti artist? Doodles, often created in spaces I have no control over such as classrooms, act as self-defence from boredom. The scribble maps an alternative imaginary space. With this map, I am no longer a frustrated student, but a ticket-holder to the subversive lands of surrealism. The doodle itself is pure automatism and was created on a separate piece of paper, then collaged to different objects and images. By chance, it adhered to the cow, resulting in an image that surprised myself.

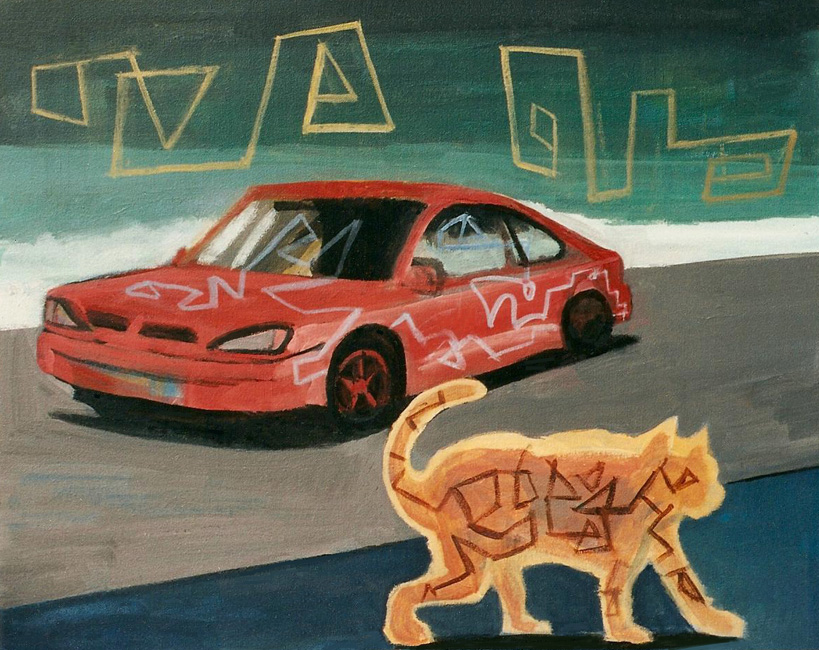

I later did a painting of a cat, car and star constellation, each marked by a similar geometric maze pattern. The pattern itself is meaningless apart from its context. I offer three different contexts in the cat, car and constellation, chosen in part because I liked the sound of the title. Patterns appear in living creatures, in objects and in landscapes, encouraging analogies and relationships. In my painting, the doodle swirl is both absurd and decorative, and functions as a source of chaotic energy. I contrast the swirls enclosed inside shapes with an unconstrained swirl that dances freely across the sky.

The Doodle Mandorla

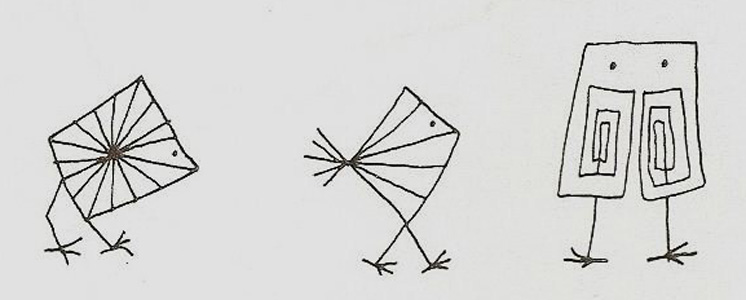

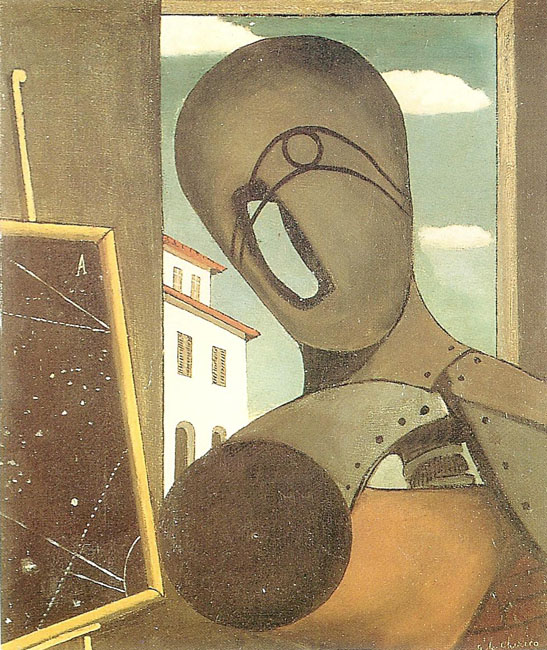

The doodle as a form of energy led me to “the doodle mandorla,” one of my favourite motifs. A mandorla is a full-body halo, usually almond- shaped, that appears in many religious paintings of Christ. It is a cloud or ring that surrounds and encloses a body to indicate a spiritual condition. In secular iimages, the mandorla is used less as a symbol and more as an attention-grabbing device. It is also a kind of doodle–tracing lines around the outside shape of a figure in a series of expanding rings. My painting contrasts the invisible flight lines of the birds with the visible growth rings of the tree. Both flight lines and rings mark a passage in time as well as an expansion in space.

At the time I made these paintings, I had been struggling to find a way to translate cartoons of mine into paintings and here was something less than a cartoon–the merest of doodles–that miraculously found its place within a painting. The doodle also helped me overcome a fear of abstraction. To me, the oscillation from abstraction to representation and back again, is central to any art experience.

I stopped creating art for a few years as I went back to school to study art history and the French language. It was a wonderful experience, but stressful at times. I was living in Montreal, away from my wife and friends, and found I couldn’t sleep at night. I asked myself: how can I possibly unwind? How can I think no thoughts so I can relax enough to fall asleep? The answer was simple. A return to doodling, drawing on index cards one mad sketch after another. Never erasing a line or pausing to think, plan or evaluate. As I scribbled away, I relaxed and began to drift off. The drawings became looser and looser. In the morning, I would look at the doodles and laugh. Out of 10 drawings, I threw 9 of them away. But the drawings I saved began to add up. In no time I had 100 drawings, then 500. I wondered how long I could keep it up and began to think of my activity as a series of drawing games.

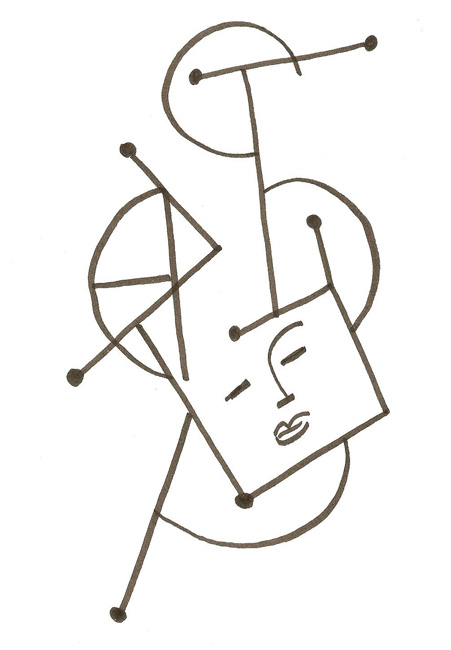

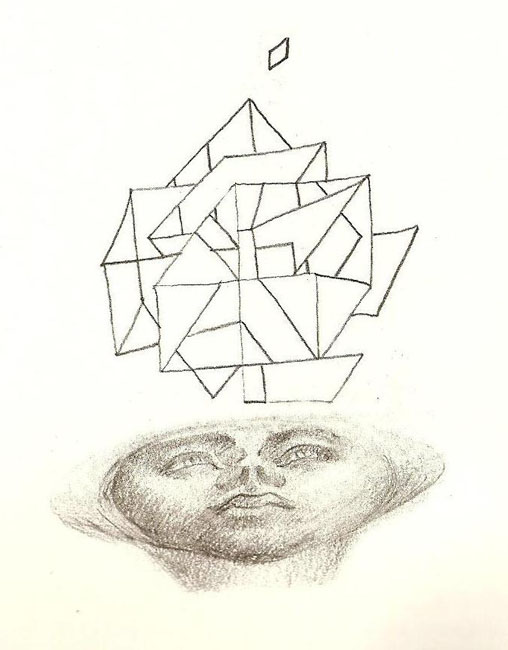

The above drawing is a recent example–one of my “constellation games.” Draw two dots and join them with a line. Keep drawing dots until you’ve covered different areas of the page. I supplemented the lines and dots with four half circles to break the linear pattern and imply another kind of motion. Finally I added the face in a squared-off area that looked to me like a screen. I wanted to suggest someone in the middle, a user or creator, who is unconcerned by these elaborate construction lines. The drawing expresses how I think of doodles as something that one is in the middle of. Not so much a maze as a piece of architecture or a network that seeks out connections with other things. A doodle may be aimless but, used in the right context, it can be full of associations. Chaos. Energy. Decoration. Connectivity. Motion. Whimsicality. Escape from boredom.